My previous post on “Celebrating Mixed Religion: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Syncretism,” explored the impact of Paganism’s encounter with Christianity: from the choice to celebrate Jesus’s birthday near Winter Solstice to Christmas retaining many pagan holiday trappings — from yule logs to feasting to decorating evergreen trees, traditions that pre-date the historical Jesus by millennia. Similarly, we saw the ways the word Easter comes from the fertility goddess Oestre; hence, the carried-over pagan practice of decorating eggs and having children take pictures with oversized bunnies (both fertility symbols) on the occasion of remembering the stories of Jesus’s resurrection.

And although the Pagan influence on Christianity continues to today, as Christianity became the dominant religion in the Roman Empire, the complex relationship between Christianity and Paganism was increasingly covered-up. As often happens with competing groups, the leaders of one group (in this case, Christian leaders) began to define themselves in opposition to another group (in this case, pagans). The result is a classic case of ‘other-ing’: creating an “us vs. them” dynamic, exaggerating differences between two groups, and building solidarity within one group through scapegoating another.

Fast forward two thousand years: and when many people in the Christian-influenced West encounter the word “pagan,” common associations include ungodly, irreligious, infidel, and idolatrous. Those stereotypes reflect not an impartial reality, but rather the ways self-appointed enemies of Paganism tried to define Paganism. In contrast, pagans would describe themselves very differently. To turn the tables, many people associate words like “hypocritical,” “bigoted against homosexuality,” “sheltered,” and “judgmental” with the word Christian, which is different both from how many Christians would describe themselves, and from how Christians, at their best, have stood on the side of love, forgiveness, and mercy. So what does “Paganism” or “Christianity” mean? It depends both on whom you ask and when.

There have been significant shifts in the meaning of the words “Christian” and “Pagan,” starting in particular with the Roman Emperor Constantine’s strategic (some would say cynical) political choice to support Christianity in the early fourth century — but that’s almost three hundred years after the life of the historical Jesus. As historians have shown — such as Edward Watts in his book The Final Pagan Generation (University of California Press, 2015) — for thousands of years before Jesus and even for centuries after Jesus, the people who have come to be viewed in retrospect as ‘pagans’

had no name for themselves in [that] period and did not conceive of themselves as any sort of unified confession…. Pagans had a tremendous diversity of beliefs and practices. Not all pagans were polytheists, they had no common creed, and they observed or ignored gods, rituals, and festivals according to their own individual inclinations…. [That being said,] ‘pagans,’ however imprecise the term, is preferable to a longer phrase along the lines of ‘non-Jewish devotees of traditional Mediterranean gods.’ (221, fn 2)

Historically speaking, as James J. O’Donnell has shown in his book Pagans: The End of Traditional Religion and the Rise of Christianity (Ecco, 2015), even for centuries after the life of the historical Jesus, the Latin word paganus, simply meant ‘peasant’: “A pagus was a country district, a paganus someone who lived there…” (160). Likewise, the word heathen originally meant someone from the “heath,” someone who lived in the country, not the city. As with the word “pagan,” it was only later that the word heathen acquired negative connotations such as infidel, idolater, or heretic.

A major reason that the country-dwelling pagans and heathens came to be pejoratives was that Christianity for the most part was an urban phenomenon. The rate of people converting to Christianity was much higher in the cities of the Roman world than in the country. So those pagani, who remained in the heath and continued to celebrate their traditional local gods, became increasingly grouped together as a stigmatized, non-Christian other.

And, as strange as it may seem to us today, historians invite us to see that “pagans didn’t exist” until well after the life of the historical Jesus. The word paganus did exist, meaning “peasant,” but it didn’t have anything like the meanings it has come to have over time. Before the meaning of the word ‘pagan’ shifted, classicists such as O’Donnell tell us that:

There were people who lived here and there, people who spoke this or that language, people who were rich or poor, people who attended this or that festival because they enjoyed it, and people who were so tired and poor and ill that they just got through the day as best they could. It was the Christian who came along and called all those people by one name…. Centuries at least would pass still before anybody firmly outside the Christian community ever used the word to describe [her or] himself. Even more time would pass before anybody would not only use the word but accept it and take a little pride in it” (162-163).

Another way of thinking about this dynamic is that if you were able to travel by time machine, meet Julius Caesar, and ask him what it was like to be a pagan/paganus, “He wouldn’t have understood what you could possibly mean.… No one else would have understood either” (163).

And while this historical shift can seem strange, it is not altogether uncommon. To give a parallel example, scholars have shown that, “The name ‘Hinduism’ that we now use is of recent and European construction.” Similar to the way that Christians imposed the word Paganism on a diverse group of people, Hinduism is a term that European colonialists imposed on the wide diversity of cultural groups living in and around the Indus River. And whereas the European colonialists sought to group these people by religion, these same people living around the Indus River tended to divide themselves not by religion, but “on the basis of locality, language, caste, occupation, and sect.” But to confuse the matter further, Hindu has become “the word that most Hindus do use now to refer to themselves.” Again we see that definitions depend on whom you ask and when.

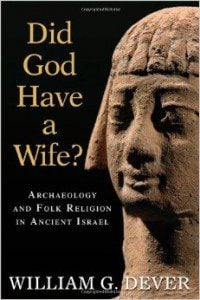

Returning to our focus on Paganism, a common theme when adherents describe what draws them to Paganism is gender egalitarianism: a strong tradition of both male and female aspects of the divine in gods and goddesses, as opposed to the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, which have a strong patriarchal bias of seeing the divine as masculine. Another common theme is the transformation many people experience through participatory pagan ritual: singing, dancing, creating altars and other sacred spaces and rites. Yet another common theme, and the one that resonates with me most strongly, is the emphasis in Paganism on connection to the Earth and the turning of the seasons, known as the Wheel of the Year.

is gender egalitarianism: a strong tradition of both male and female aspects of the divine in gods and goddesses, as opposed to the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, which have a strong patriarchal bias of seeing the divine as masculine. Another common theme is the transformation many people experience through participatory pagan ritual: singing, dancing, creating altars and other sacred spaces and rites. Yet another common theme, and the one that resonates with me most strongly, is the emphasis in Paganism on connection to the Earth and the turning of the seasons, known as the Wheel of the Year.

If you imagine a year as a circle, most of us are familiar with the four major quadrants: Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. Paganism adds the additional nuance of cross-quarter days, which further divides the year into a total of eight turning points in the cycle of seasons:

- In between Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox is Imbolc, an opportunity to celebrate the lengthening daylight. (This pagan holiday has been secularized in our society as “Groundhog’s Day.”)

- In between Spring Equinox and Summer Solstice is Beltane, most famous for the tradition of dancing around a May Pole. (Another pagan holiday that has been secularized — in this case as “May Day.”)

- In between Summer Solstice and Fall Equinox is Lammas. On the opposite side of the wheel from Imbolc, Lammas is an opportunity to ritually commemorate the days growing darker.

- In between Fall Equinox and Winter Solstice, is Samhain (also known as All Hallow’s Eve or Halloween), a time in particular, for remembering your ancestors.

In our technology-filled world of 24/7 connection and almost continually-available artificial light, the eight points on the Wheel of the Year offer a way of redirecting our attention back to the cycle of the seasons and how they affect us. The value of this Earth-centered way of being in the world was recognized officially by the Unitarian Universalist Association in 1995, when a Sixth Source was added to the UU Living Tradition: “Spiritual teachings of earth-centered traditions which celebrate the sacred circle of life and instruct us to live in harmony with the rhythms of nature.”

One growing tradition is increasing numbers of Pagan groups hosting a Pagan Pride Day. Pagans are “Coming Out of the Broom Closet!” Modern Pagan Pride events began in the early 1990s and have grown to include tens of thousands of people annually. The price of admission is traditionally not money, but rather a contribution for a local food bank. According to the website of the Pagan Pride Project:

In 2013, there were 98 Pagan Pride events across the USA, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Rome and Austria. 2013 event attendance was 65,717: an increase in attendance by over 20,000 when compared to 2012. The events collected a total of 39,962 pounds of nonperishable food…. For decades Pagans have been wrongly accused of practicing devil-worship and performing “black magic.” In reality most Pagans enjoy a religion emphasizing respect for nature, humanity, and oneself. Modern Paganism, or Neo-Paganism, is a growing religious movement based on combinations of ancient polytheism, modern eco-spirituality, and reverence for the Divine as both masculine and feminine.

The Pagan path is not for everyone, but I invite you to consider what wisdom there may be for you in the “Spiritual teachings of earth-centered traditions which celebrate the sacred circle of life and instruct us to live in harmony with the rhythms of nature.”

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a trained spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism:

http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles