From the theologically conservative Christianity of my childhood, I learned to read the Bible literally—as a record of history as it had actually happened. And although I would occasionally question details that did not make sense, I was also influenced by the signifiant number of people around me who seemed to unquestioningly accept the Bible as factual. Only later did I come to see that likely many more people in my childhood congregation did have questions about the Bible’s historicity, but did not feel comfortable asking them aloud.

I was also taught to read the Hebrew Bible as the Christian “Old Testament.” Instead of studying the original context of these books within the Jewish tradition, I was taught that they were valuable primarily for the ways they were understood to have predicted events in the life of Jesus. As a child, placing Jesus at the center of “life, the universe, and everything” did not seem strange. After all, the calendar in widespread use around the world literally counted the years from before and after Jesus’s birth.

But as I grew up, I began to encounter other perspectives. And I was increasingly struck by the differences between how Jews and Christians often read the exact same sentences in irreconcilably different ways. Along these lines, the Yale literary critic Harold Bloom has said, “Christianity stole our watch and has spent 2,000 years telling us what time it is.”

Today, the western calendar may tell us that the year is 2017 A.D. (Anno Domini, meaning “in the year of our lord” in reference to Jesus), but some of you will recall the challenge of the evolutionary evangelist Michael Dowd, who spoke here a few years ago, that from our twenty-first century perspective, we need to shift our paradigm of “B.C.” from “Before Christ” to “Before Copernicus,” the astronomer whose 1543 book On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres presented scientific evidence that the Earth is not the center of the Universe.

In the 500 years since, we have come to see that the de-centerings we face as a species are far more profound than Heliocentrism, After Darwin, we know that we humans are not “a little lower than the angels,” but merely a “little higher than the apes.” After Einstein, we know that even space and time are relative to one another. Science tells us that rather than Jesus being at the center of history, we humans are an infinitesimal part of a much larger universe story that has been unfolding for more than 13.8 billion years across more than two trillion galaxies.

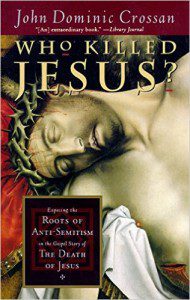

So if Jesus is not at the center of history, then what does twenty-first century scholarship tell us about the Quest for the Historical Jesus and how we might best understand the original context of the texts that we know today as the Bible? One of the turning points in my own understanding came from reading John Dominic Crossan’s book Who Killed Jesus? which asks if the passion narratives—the stories about Jesus’s death (from the Latin passio, meaning “suffering”)—are “history remembered” or “prophecy historicized” (x)?

So if Jesus is not at the center of history, then what does twenty-first century scholarship tell us about the Quest for the Historical Jesus and how we might best understand the original context of the texts that we know today as the Bible? One of the turning points in my own understanding came from reading John Dominic Crossan’s book Who Killed Jesus? which asks if the passion narratives—the stories about Jesus’s death (from the Latin passio, meaning “suffering”)—are “history remembered” or “prophecy historicized” (x)?

As a child, I was only taught the perspective of “history remembered”: that the Christian scriptures were accurate historical records passed down from generation to generation. Part of the alleged “proof” that was often cited is that hundreds of years before Jesus, the Hebrew prophets claimed to have predicted with shocking accuracy the events around Jesus’s death. In contrast, the perspective of “prophecy historicized” holds that the direction of influence is reversed. Instead of the prophets predicting the future, Christian authors—decades after Jesus’s death—reached back to draw on words, themes, and sequences from the Hebrew Bible in drafting their Gospels (4). So passages in the Hebrew Bible, which originally had been about their own time and place—hundreds of years before Jesus—later became seen as proof of predicting details about Jesus’s death in the future. The prophecy became historicized.

Let me give you some examples. I was raised to read Jesus’s final words from the cross in Mark 15:34 as if a journalist had been there taking notes for posterity: “At three o’clock Jesus cried out with a loud voice, ‘Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?’ which means, ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’” Later, as I began a more academic investigation into the Bible, it was pointed out to me that those precise words are at the beginning of Psalm 22: “1 My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? Why are you so far from helping me, from the words of my groaning? 2 O my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer; and by night, but find no rest” (133-134). A “history remembered” view would argue that Jesus must have been quoting the words of the Psalmist in his hour of distress. That’s possible. But a “prophecy historicized” view would invite us to consider that, tragically, no one knows what Jesus’s last words were. Jesus’s followers scattered after his arrest, and likely would not have been present at his death.

Another exact parallel from the crucifixion jumps out, one chapter later, in Psalm 22:18: “They divide my clothes among themselves, and for my clothing they cast lots.” Again, was this an early prediction of what became history remembered—or were these details from the Psalm woven into a later reconstruction of what Jesus’s death may have been like? Maintaining a “history remembered” perspective becomes increasingly difficult to maintain as one studies example after example of the many places from the Hebrew Bible where exact words, phrases, and sequences were imported into the passion narratives.

Even many theologically orthodox biblical scholars will admit that at least 20% of the stories about the death of Jesus are prophecy historicized, while still maintaining that about 80% are history remembered. But more progressive scholars such as Crossan go much further, convinced that the passion narratives are approximately 80% prophecy historicized and only 20% history remembered (1). That percentage is in line with the Jesus Seminar’s famous pronouncement that Jesus only said about 20% of the words attributed to him in the Gospels. In some ways these statistics are not surprising: the Gospels are almost entirely written in the third-person, do not claim to be composed by eyewitnesses to the historical Jesus, and were written at least four decades after Jesus’s death. To give you another example, looking again at Mark, the earliest of the four canonical Gospels: Mark 15:33, in isolation from a “history remembered” point of view, can seem like a straightforward recording of events: “When it was noon, darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon.” But a perspective of prophecy historicized invites us to consider the ways that Amos 8:9-10 was used to craft the narrative of how the crucifixion might have happened: “On that day, says the Lord God, I will make the sun go down at noon and darken the earth in broad daylight…. I will make it like the mourning for an only son…” (2-3).

Or consider the way the story of Judas betraying Jesus during the Last Supper may have been inspired by Psalm 41:9: “Even my bosom friend in whom I trusted, who ate of my bread, has lifted the heel against me” (69-70). Or regarding the words allegedly spoken from heaven at Jesus’s baptism, those come from Psalm 2:7: “I will tell of the decree of the Lord: He said to me, ‘You are my son; today I have begotten you” (82-83). Are these examples of history remembered—or prophecy historicized?

As you start to closely compare the passion narratives and the Hebrew Bible, the case becomes strong that:

- any mention of spitting and nudging comes from the popular scapegoat ritual;

- any mention of scourging, buffeting, and spitting comes from Isaiah 50:6

- any mention of piercing, seeing, mourning comes from Zechariah 12:10;

- any mention of disrobing, rerobing, or crowning comes from Zechariah 3:1-5. (132)

Crossan lays out these and many other examples in his book in ways that allow his readers to compare precisely how the earlier texts influenced the later ones. Hopefully, the examples I have given offer a taste of this perspective. His book Who Killed Jesus? is an accessible read if you are interested in learning more.

(I will continue this topic tomorrow in a post on “How the Christian Gospels Became Increasingly Pro-Roman & Anti-Jewish.”)

The Rev. Dr. Carl Gregg is a certified spiritual director, a D.Min. graduate of San Francisco Theological Seminary, and the minister of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Frederick, Maryland. Follow him on Facebook (facebook.com/carlgregg) and Twitter (@carlgregg).

Learn more about Unitarian Universalism: http://www.uua.org/beliefs/principles