A friend of mine posed the following question recently on Facebook:

You may have written about this before but how about dry times in prayer? What to do? Does it really mean anything? Can we have an impact on it or do we patiently wait it out?

The fancy term here is “aridity.” I suspect anyone who has attempted a sustained, daily (or at least regular) practice of prayer encounters this sooner or later. A sense of dryness, as if our prayers are parched. If we pray with words (whether our own or someone else’s), it seems as if the prayers are bouncing off the ceiling. If we choose instead to settle into the silence of a more contemplative form of praying, all we encounter is fidgetiness and restless, random thoughts. “Distracted from distraction by distraction,” as T. S. Eliot put it.

So it’s a universal aspect of prayer, or at least it seems to be. The only way to dodge aridity is, well, to stop (or never start) praying. But I’m assuming anyone who is reading this blog is at least somewhat committed to prayer, so quitting is not an option.

To repeat my friend’s questions: what does this mean, and how can we respond to it?

I think the first important point is to acknowledge just how common, perhaps even universal, aridity is. What this means is that if you are experiencing dryness in your prayer, that’s a good sign — a sign you are making progress in your spiritual journey.

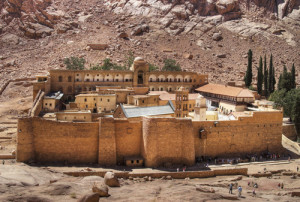

Think of it this way: for Moses and the Hebrew people, the path to liberation from slavery in Egypt took them through the desert. Elijah’s vocation as a prophet began with a sojourn in the wilderness. Likewise, Jesus’s earthly ministry began with his 40 days in the desert. And the very headwaters of the post-Biblical tradition of Christian contemplative and mystical spirituality began… in the desert — the deserts of Egypt, Syria, and Palestine.

If you want to be physically fit, you got to work out. If you want to master a musical instrument, it takes hours of dedicated practice. And even though spirituality is always shaped and surprised by grace, there is still a “practice” element to it — in other words, if we want to grow in our response to the love of God, our path will take us through the desert.

My second thought is to recall that even the desert has its own austere beauty.

I remember the first time I travelled around Ireland, and came to a region called the Burren — the closest thing Ireland has to a desert. It’s a windswept wasteland covered by limestone which looks like what I imagine the surface of the moon to be. It’s a stark contrast to the lush, verdant landscape that we normally associate with the Emerald Isle — and yet, in its own stark way, the Burren is lovely.

I was stunned at how beautiful it was. I expected, after seeing so many picture-postcard scenes of the Irish countryside, that the Burren would just feel empty and sad. But that was not the case at all. Yes, it was empty, and I suppose it even had a sadness about it. But it was a lovely sadness, a gorgeous emptiness.

The lesson here for us as we encounter aridity in our prayer is that such times of dryness may actually be invitations to find beauty and meaning even in the emptiness, the austerity, the sense of aloneness or the sense of fidgetiness and distractedness. Most important of all, is to discover that God loves us just as we are: desert-like warts and all.

God is not just interested in a never-ending succession of happy times, where we put on a brave face or our party hats and approach prayer as just another way to greet life with a smile, no matter what’s going on inside. God wants our hearts, not our masks! God wants us precisely when we are bored, or fidgety, or restless, or distracted, or unhappy.

God wants to pour God’s love into us in whatever state we may find ourselves in. Aridity in prayer is a gentle invitation to bring our lives in their messy imperfections to the God who so dearly loves us.

Of course, part of the challenge of dryness in prayer is that we don’t feel anything — so if God is loving us through the aridity, it seems like we are the last ones to get the memo. But what we lack in awareness, we more than make up through growing in faith. Faith, by its very nature, requires times of darkness, or unknowing, or dryness, in which we get to “work out the faith muscles” — and just like a physical workout at the gym, we experience it as painful, or difficult, or fraught with resistance.

But at a level deeper than our awareness, our muscles are growing. And so it is with faith: the “resistance training” that aridity or other times of darkness or unknowing bring to us, allow our faith to grow, even at a level deeper than our conscious awareness.

So what, then, to do? When I am waist-deep in the sands of the desert, what should be my response, my “prayer game plan”?

My friend is right: the key here is patience, perseverance, and I would add, trust. Part of what makes the dry times so unpleasant is the fact that we can’t fix or manage it. So we’re invited to respond not with our American “can-do” mentality, but with something much more primal: the opportunity to simply trust in God, God’s presence, God’s work in our hearts below the threshold of our awareness.

Such trust works best when we approach it mindfully. In other words, when our prayer takes us into the desert, pay attention to the fact that you have hit a dry spell. Don’t try to fix it, or wish it away, or pray it away (as if you could). But don’t ignore it, either.

You might find yourself in a place where lamentation emerges from your heart and your lips. Alleluia! Lamentation is such a beautiful way to pray and something that our culture often forgets (because we are so busy reassuring God that we’ve got everything under control, even when all hell is actively breaking loose).

So I would recommend to anyone struggling along the path of aridity to keep these three key elements in mind:

- Trust that God is in control, that aridity is a normal aspect of a mature and serious prayer practice, and that beneath our conscious awareness, the Spirit is using such dryness to help us grow in faith and love;

- Attentiveness to the fact that what arises, arises; by being present to the darkness or dryness or distraction or unknowing, our prayer is authentic even if it doesn’t necessarily “feel” good;

- Lamentation — or whatever else arises — recognizing that God desires us to be authentic and honest in our prayer, so praying into the dryness and unknowing is perhaps the most direct path through it.

I hope this is helpful!

Do you have any suggestions for how Christians can deal with dryness or aridity in prayer? If so, please leave your thoughts as a comment to this blog post (or share with me on Facebook or Twitter). Thank you!

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.