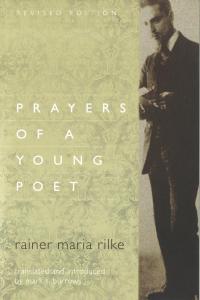

Today’s guest post is by Mark S. Burrows, translator of Rilke’s Prayers of a Young Poet.

Of Rainer Maria Rilke’s many extraordinary poems collected in Prayers of a Young Poet, #18 beckons us to an extraordinary insight, one startling for those already familiar with his writings or those for whom he is a complete unknown.

Of Rainer Maria Rilke’s many extraordinary poems collected in Prayers of a Young Poet, #18 beckons us to an extraordinary insight, one startling for those already familiar with his writings or those for whom he is a complete unknown.

To understand its frame of reference, remember that Rilke wrote these poems as if they were penned by an old Russian Orthodox monk and icon painter (or, as the Orthodox would have it, an icon “writer,” since these images were like texts to be “read” with the heart).

In this poem, the painter opens the poem sounding a note of resignation, despairing of his work as being up to capturing the divine—and who, among us, has not faced such a feeling of futility:

Why do my hands go astray with the brushes?

Whenever I paintYou, God, You barely notice.[1]

Granted that this is poetic metaphor and not literal description, what Rilke is admitting is something each of us knows something about: no matter how strong our faith is, there are days—or seasons, perhaps long ones—when God seems distant from us.

Perhaps altogether absent. Far from the reaches of our faith. Perhaps even “unconcerned” with our efforts at communicating.

Prayer that does not teach us this has not yet gone far. And, in such moments, doubling down with our efforts at believing generally has little or no effect.

God May Seem Distant to Us — But We Don’t Seem Distant to God

In the lines that follow, however, we sense a strong shift:

I feel You. You begin to tremble

on the hem of my senses as with many islands—

and to Your eyes that never blink

I am the room.

Now, on the surface of things, this is almost nonsensical: our senses do not have hems. And what is this bit about islands? And: God’s eyes blinking? Really? And, what in the world would it mean to say, “I am the room”?

I can’t answer such questions with absolute certainty, and do not come closer to understanding what the poet is after if I remain on the literal level of language, though I can tell you that Rilke favored this simple “outer” word—“room,” or Raumin the German—to speak of the dynamics of our “inner life.”

To grasp the power of this “doubling,” one has to learn to play with these images. Or, rather, let them begin to play with us.

How do we do this? Try imagining God “trembling,” admittedly a strange image. But at its root, it is one of utter vulnerability—in this case, toward us. I understand this when I think of my now grown daughters, in times when they were struggling.

And the island scene starts to make sense here, too: land separated with water, but still somehow within reach of the eyes. Every parent knows something of this, and we might well remember it—if we are fortunate—in the trusting presence of a loving parent or elder abiding with us through a time of crisis.

And so the poem begins to unfold its wisdom: to imagine God’s eyes never blinking, when I am facing a tough stretch, is a comforting image. But what follows, though as strange, opens me to depths of feeling I would not easily find along a more direct path: “I am the room.”I am the place where You, God, seek to find a home.

The poem continues with this imaginative approach, suggesting that God has “chosen” to move apart from the conventional religious “location” of angels in their ranks (and, for Rilke, their “angel-dances”), choosing to dwell in what he calls God’s “outermost house.”

Far from the conventional, from something within easy reach.

God Comes… Not to Speak, But to Listen

But perhaps we are the ones who have removed ourselves, first of all, from such a “place,” and discover—to our surprise—that God, too, is tired of being domesticated in such religious conventions as angels in their dance.

But perhaps we are the ones who have removed ourselves, first of all, from such a “place,” and discover—to our surprise—that God, too, is tired of being domesticated in such religious conventions as angels in their dance.

The last lines move the poem to a poignant place of startlement:

Your whole heaven listens within me,

for in my pondering I didn’t speak myself to You.

Here, the unexpected, given the poem’s starting point, which began with resignation or even despair: he comes to sense that God is “listening” within him.

What a strange, and yet strangely luminous image: God, envisioned in his “wholes heaven,” does not come to speak to us, but draws close to listen within us, who in the midst of our inner turmoil—from God, from ourselves, from others—had lost the capacity to speak, to “open” ourselves to God, to ourselves, to others.

What would it mean, in times of unbelief, of confusion, of inner crisis, to imagine God coming from some “distant” place to dwell within us? Or, more to the point, to listenwithin us?

This is the kind of friend we need in dark times.

And here, Rilke imagines God doing just this, in the midst of the pondering that sometimes renders us mute. God, listening within us? God, listening within you?

About today’s guest contributor: Mark Burrows is a poet, editor, medievalist, and professor of religion and literature at the Protestant University of Applied Sciences in Bochum, Germany. His poems and translations have appeared in numerous journals. His works include translations of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Prayers of a Young Poet, the German-Iranian poet SAID’s 99 Psalms, and Meister Eckhart’s Book of the Heart (with Jon M. Sweeney). His poetry is collected in The Chance of Home.

About today’s guest contributor: Mark Burrows is a poet, editor, medievalist, and professor of religion and literature at the Protestant University of Applied Sciences in Bochum, Germany. His poems and translations have appeared in numerous journals. His works include translations of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Prayers of a Young Poet, the German-Iranian poet SAID’s 99 Psalms, and Meister Eckhart’s Book of the Heart (with Jon M. Sweeney). His poetry is collected in The Chance of Home.

[1]See Rainer Maria Rilke, Prayers of a Young Poet, translated by Mark S. Burrows (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2016) [no. 18].

Enjoy reading this blog?

Click here to become a patron.