When Adam awoke at the beginning of the sixth day, his body must have been one of the first things to come to his attention. Everything else that surrounded him, the sticky leaves opening on the branches, the cool waters of the four rivers running through the garden, the sun slowly makings its way across the carefully ordered heavens, all came to him through the body. We are told that the angels understand things by “pure intellection,” that is, they understand abstract concepts without the sort of direct, concrete experiences that you an I rely on for knowledge. God, likewise, understands simply as an act of His being. Adam, however, understands through the senses. He sees a fig, picks it up, feels its skin, smells its nectar, tastes its juices, and thereby comes to have an idea of a fig.

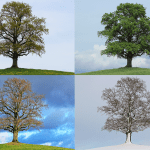

There are two interesting consequences that arise from this fact. The first is that Adam is always in some way divorced from things “in themselves.” He can’t just behold a thing from a purely objective standpoint and have an immediate knowledge of its nature and essence. Whatever it is that a fig is in the mind of an angel, it has very little to do with the fig as Adam understands it. The second is that Adam’s direct experience of things is in some sense more real than the angel’s experience. There is one kind of enjoyment that can be derived from contemplating the idea of a tree: it’s interior symmetries, the mathematical relations of its parts, the information encoded in its DNA, the logic of life by which it is sustained. There is an entirely different kind of enjoyment that can only be derived from swinging in its branches.

Whereas the angel is a mind contemplating bodies, Adam is a body amongst bodies. Yet he is also a mind contemplating his own body, and the bodies that surround him. A new kind of consciousness has come into existence, one that changes the world. Man is not merely called to “cultivate the garden” and to “till the earth” in a purely mechanical sense. He’s not just going to plough furrows and plant seeds and prune berry bushes. He is also going to receive the seeds of bodily experience into the furrows of his mind and reap a rich harvest of new insights into the Creation which God has made. Adam beholds the world with a new kind of gaze, and in beholding it, he bestows on it a new kind of meaning.

This, I think, is the meaning of the naming of the animals. Obviously God had His own names for donkeys and lions and cows: the sort of names that cause things to exist simply because the word is spoken into the void. Presumably these names were also known to the angels. Yet God calls together all of the species with which He has populated the world, and He presents them to Adam in order to gain a different kind of name. A name in human speech, a name derived from this particularly human kind of knowing. The names which Adam bestows are “perfect,” in the sense that they completely reflect and contain the entire insight which Adam has into each of the creatures that he names. It is only after Babel that this original language is lost, and a confusion of imperfect words takes its place.

This bestowing of names, or meanings, is not over after Adam has finished going over the created realm. Each human being since has been given this task anew, and each one performs it in a way that is unique. This is most noticeable in the arts, where you can immediately see that Michelangelo is seeing something very different from Modigliani when he is looking at a human body, or that Van Gogh and Gainsborough have utterly distinct perspectives on the natural world. It is all the more true of interior experience, which joins sensory impressions to spiritual thoughts in order to draw out new and different meanings from the same material. We are all audience members and participants in the greatest show in the galaxy, and each of us takes something different from the performance. All of these perspectives will be brought together at the end of time in the Communion of Saints. They will united and reconciled through the incarnate Christ, and will enter into the totality of Creation, the consummation of the world. That, however, is still far away when Adam first opens his eyes and sees the olive branches swaying overhead.

Returning to the Theology of the Body, we have reached a point where Adam is aware of two important things: he is aware of his own body, and of the ways in which the body opens and reveals the world to him, and he is aware also of his mind, which places him in a special relationship to God – a relationship that makes him different from the animals to which he has just given names.

Photo credit: Pixabay