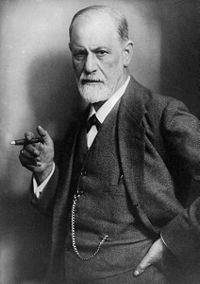

In Richard Beck’s recent book, The Authenticity of Faith, he considers whether a truly authentic faith is possible. Freud had dealt a heavy blow to Christianity by offering up scientific explanations for what motivates religious belief. Believers are drawn to religion because it functions to repress our existential anxieties. Afraid of death? Don’t worry, there’s an afterlife. Need some meaning and  purpose for your life? Christianity gives you plenty (God loves you and has a wonderful plan…). Feel insignificant in this big bad world? You are one of the elect! Struggling with the problem of evil and suffering? God’s in control and has a plan for everything. Christianity (and other religions too) helps you repress your fears and deal with your anxieties. That, said Freud, is the reason for religious belief.

purpose for your life? Christianity gives you plenty (God loves you and has a wonderful plan…). Feel insignificant in this big bad world? You are one of the elect! Struggling with the problem of evil and suffering? God’s in control and has a plan for everything. Christianity (and other religions too) helps you repress your fears and deal with your anxieties. That, said Freud, is the reason for religious belief.

Beck suggests that Freud’s analysis is the greatest apologetic challenge facing Christianity today. Not proving the existence of God (as if that were possible) or arguing for the perfection of Scripture or rationally explaining the mystery of the Trinity or solving the problem of evil. The new apologetic is to show that Christian faith is real, or authentic–it’s much more than a handy instrument of repression for weak souls. It’s hard to disagree with his analysis. As a fan of Kierkegaard, I’m already cognizant of the limitations of classical apologetics for eliciting belief. And for Kierkegaard, the problem of “Christendom” was precisely the lack of authentic faith. His entire project was aimed at the deconstruction of idols and the recovery of existential authenticity: the “self” before God.

Freud’s influence can be seen all over the internet, on blogs and discussion forums. Religion is a sham. It’s a prop. When are you going to wake up, realize your (self) deception, and own up to the existential meaningless of this world? It’s a material world, just like Madonna said. Critics don’t seem to be talking about errors in the Bible or contradictions in key doctrines anymore. They go straight for the jugular.

Beck does not see Freud’s challenge as a fatal blow to religion, however, but an opportunity. He asks, “What would religious faith look like, experientially and theologically, if it were not engaged in existential repression or consolation?”

Beck shows that there are people out there–believers–who do are not motivated to believe in Christianity because it gives them an existential prop. Rather, they believe in spite of their honest realization of the absurdities of life and they face up to to the intellectual and emotional challenges of the flux and flow of existence, while yet retaining belief in God. They are, in Beck’s term, “Winter Christians.”

These Winter Christians are akin to Kierkegaard’s “knight of faith,” in Fear and Trembling, who believes in God not because of what he gets in return, but in spite of–or even on the strength of–the absurd.

These Winter Christians are akin to Kierkegaard’s “knight of faith,” in Fear and Trembling, who believes in God not because of what he gets in return, but in spite of–or even on the strength of–the absurd.

I’m wondering, though, if it’s possible to be a “fall” or “spring” Christian and still have an authentic faith? If the only way to be authentically Christian is to be a winter Christian (or a “knight of faith”), then my only option, like Johannes de Silentio (Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous author of Fear and Trembling), would be to simply “admire” the knight of faith or the winter Christian and go on my merry (summery) way.