Dr. Richard Land, president of Southern Evangelical Seminary, which is located in Charlotte, North Carolina, takes Dr. Richard Mouw, just-retired president of California’s Fuller Theological Seminary, to task for going too easy on Mormon doctrine:

http://www.onenewsnow.com/church/2016/05/23/seminary-leaders-disagree-about-mormons-beliefs

“The foundational doctrine of Mormonism,” declares Dr. Land, “is that God is eternal but Jesus is not.”

Curiously, it would never have occurred to me to describe that as “the foundational doctrine of Mormonism.” In a very real sense, moreover, it’s not even true. That is, it’s not a doctrine of Mormonism at all.

You could argue, for example, that, in Mormonism, the Father qua Father may not himself be eternal. More securely, you could point out that, in Mormonism, both Father and Son are eternal and uncreated, and in much the same sense.

But I’m getting far afield. I would have thought, rather, that the absolutely bedrock fundamental doctrine of Christianity — and, equally, of the Mormon variant of Christianity — must surely be something like the declaration of 2 Corinthians 5:19 that “God was in Christ, reconciling the world unto himself.”

Of course, from another vantage point, one might identify the resurrection of Jesus as the foundation stone of Christianity. But, here again, this is a doctrine affirmed by Mormonism as well as by most other Christians.

And it’s taught over and over and over again throughout the New Testament. And, yes, throughout the Book of Mormon and the other texts that are peculiar to the Latter-day Saint canon.

By contrast, there is very little in the Bible, if indeed there’s really anything at all beyond tendentious theological inferences from documents that were written for quite other intents, on which to base the declaration that both the Father and the Son are eternal.

But even if you want to single out the most fundamental distinctive doctrine of Mormonism, I would never have thought of the proposition that the Father and the Son are both eternal. Instead, I might have pointed to the notion that humans and gods are of the same species, that humanity and divinity are points on a continuum rather than radically distinct. Or, from another perspective, I might have chosen modern revelation or, much the same thing, Mormonism’s open canon and its additional written scriptures.

Moving on, though, Dr. Land’s further comment about the Mormons (the rhetorical question, “Until they get that doctrine right — the doctrine of the Trinity — how can they be approaching orthodoxy?”) is exceedingly strange.

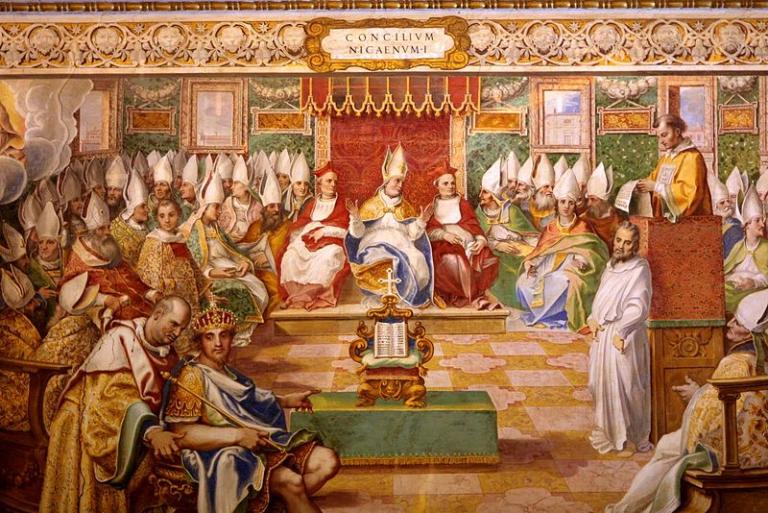

Not only does the “orthodox,” “mainstream,” Christian doctrine of the ontological Trinity seem both secondary in importance and, at best, ambiguously biblical, but its Nicene formulation didn’t even occur until the early fourth century. Generations of devoted Christian disciples lived and died — sometimes horribly killed, as martyrs — before the Emperor Constantine even convened the Council of Nicaea. (I’ll pass over in charitable silence the fact that the often raucous proceedings at Nicaea seem to have been in some ways more like the hammering out of a party platform at a contentious political convention than like a prayerful deliberation guided by the Holy Spirit.) Would most of them have been able to pass doctrinal muster with Dr. Richard Land of Southern Evangelical Seminary? I doubt it very much.

If Dr. Land is demanding, however, that Latter-day Saints affirm the existence of the Father and his divine, redeeming Son, in and through whom alone salvation is possible . . . well, we affirm our faith in them just as centrally and every bit as sincerely as any of his fellow Southern Baptists do. Mormons believe in the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost or Holy Spirit, and we believe that they are one. (The Book of Mormon and other uniquely Latter-day Saint canonical documents declare the divine unity more explicitly and expressly than does any genuine verse of the New Testament.) Surely that, rather than some incomprehensible — and very possibly logically incoherent — fourth-century philosophical notion of exactly how they are one, ought to count as “foundational.”