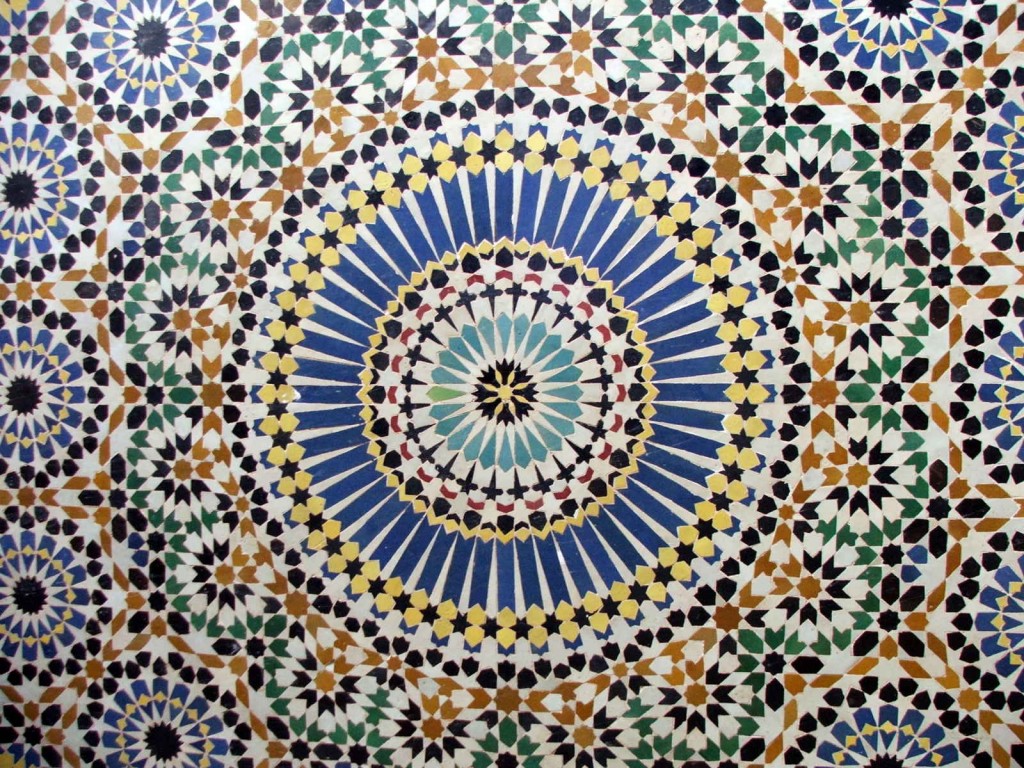

(Wikimedia Commons)

For a time, Dr. Glen Cooper, a former student of mine, was a colleague in both the Middle Eastern Texts Initiative and, thereupon, the Department of History at Brigham Young University.

I was delighted to see this profile of him in BYU’s alumni magazine:

Dr. Cooper’s field is a very important one, as scholarly disciplines go. It’s important both intrinsically and, given the lack of awareness among a sizable proportion of Americans regarding Muslim contributions to world civilization — which provides the soil in which, for too many, a deep hostility has grown — for its relevance to contemporary relations between the West and the world of Islam.

The fact is that the West and the Islamic world have always been deeply intertwined, and that Dr. Cooper’s work in the history of Islamic science and my own interest-area of the history of Islamic philosophy demonstrate that fact with exceptional clarity. The Muslims inherited Greek philosophy, logic, medicine, mathematics, and science, and then, having made significant advances in all of those fields, exerted enormous influence on the West as it began to climb out of the relative darkness that befell Europe in connection with the fall of Rome. Today, though, the West has largely forgotten its debt to people like Ibn Sina (Avicenna), al-Biruni, al-Khwarizmi, Ibn al-Haytham, and Ibn Rushd (Averroes).

I very much wish that Brigham Young University could get Dr. Cooper back. He’s an extraordinarily well trained and well regarded scholar who would be a real asset to Islamic studies at the University, and who would certainly fulfill the University motto that “The World is Our Campus.”

“It will suffice here to evoke a few glorious names without contemporary equivalents in the West: Jabir ibn Haiyan, al-Kindi, al-Khwarizmi, al-Fargani, al-Razi, Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Battani, Hunain ibn Ishaq, al-Farabi, Ibrahim ibn Sinan, al-Masudi, al-Tabari, Abul Wafa, ‘Ali ibn Abbas, Abul Qasim, Ibn al-Jazzar, al-Biruni, Ibn Sina, Ibn Yunus, al-Kashi, Ibn al-Haitham, ‘Ali Ibn ‘Isa al-Ghazali, al-zarqab, Omar Khayyam. A magnificent array of names which it would not be difficult to extend. If anyone tells you that the Middle Ages were scientifically sterile, just quote these men to him, all of whom flourished within a short period, 750 to 1100 A.D.”

George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science, vol. 1 (Baltimore: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1927).

“I have to deplore the systematic manner in which the literature of Europe has continued to put out of sight our obligations to the Muhammadans. Surely they cannot be much longer hidden. Injustice founded on religious rancour and national conceit cannot be perpetuated forever. The Arab has left his intellectual impress on Europe. He has indelibly written it on the heavens as any one may see who reads the names of the stars on a common celestial globe.”

Robert Briffault, The Making of Humanity (London, 1938).

“Looking back we may say that Islamic medicine and science reflected the light of the Hellenic sun, when its day had fled, and that they shone like a moon, illuminating the darkest night of the European middle Ages; that some bright stars lent their own light, and that moon and stars alike faded at the dawn of a new day – the Renaissance. Since they had their share in the direction and introduction of that great movement, it may reasonably be claimed that they are with us yet.”

T. Arnold and A. Guillaume, The Legacy of Islam (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1931).