Hurricane Harvey has left appalling damage in its wake, and, now, the massive Hurricane Irma is on its way. And a third hurricane is said to be taking shape out in the Atlantic.

If you were thinking about doing something to help out with the response but haven’t yet gotten around to it, here’s an easy way to do so:

Fully 100% of all donations to this fund are devoted to helping people. Unlike many other organizations, no part of any donation is used to cover overhead.

***

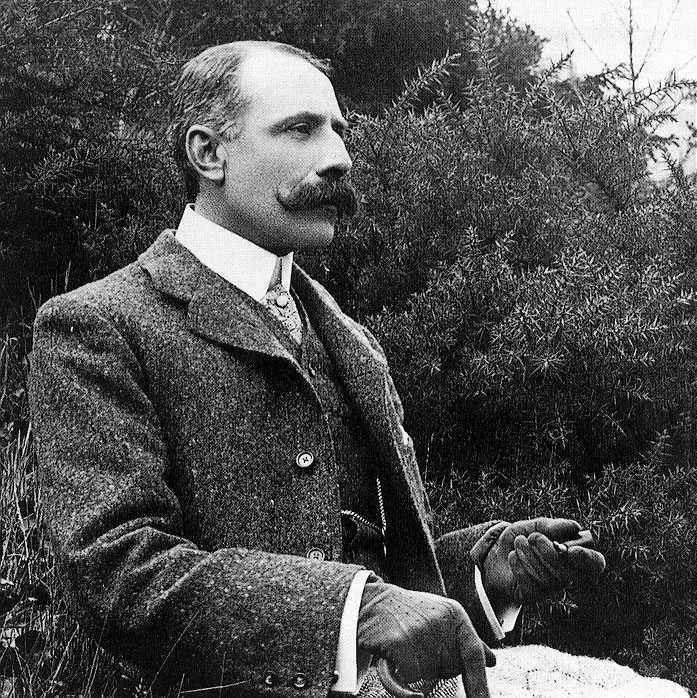

Driving back from the enjoyable lecture last night up at the Cruise Lady’s Jordan Event Center, I listened to a selection from Sir Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations on KBYU-FM. Afterwards, the host of the program related an anecdote about Elgar.

Although he certainly ranks among the greatest of English composers, Sir Edward (1857-1934) was apparently quite shy and deeply modest.

So when, at some point late in the life of Queen Victoria (d. 1901), the monarch invited Elgar to some sort of event at Buckingham Palace, he waited until the last possible moment to respond. And then he declined, saying that he felt that the distinguished aristocrats gathered at the event would not wish it to be ruined by the presence of a mere piano tuner’s son and his wife.

Perhaps it’s because I’m American and perhaps it’s because we’re living in a distinctly egalitarian age, but I find such a response — at least in the way he expressed it; not necessarily his disinterest in attending some sort of formal royal “cocktail party,” since I don’t enjoy such events either — quite mystifying.

Sir Edward Elgar should not have felt himself outclassed in the presence of a mere bunch of aristocrats who had inherited money and titles from ancestors centuries before — ancestors who, in many cases, were essentially buccaneers, extortionists, and gang leaders. Instead, Lord Nondescript, Lady Lacktalent, and Sir Reginald Bland should have been the people feeling outclassed by a man whose music is still played and admired. They are, by and large, forgotten except as dusty entries in Burke’s Peerage. And justly so.

***

I’m reminded of a story out of pre-Islamic Arabia. Perhaps I’ve told it here before, but I like it and I’m going to tell it again.

One of the great poets of the Arabic tradition is Antarah b. Shaddad, or Antar (AD 525-608). He was the son, it is said, of a Bedouin chieftain and an Ethiopian slave. True, she had been a princess, but now she was a slave, and her son was half black. He didn’t have the status of a freeborn Arab in that society.

There came a time when his father’s tribe was engaged in a fierce battle with a rival tribe, and the rivals were gaining the upper hand. Antarah was standing on a ridge overlooking the fight and, as he had been charged to do, minding the camels of the warriors.

Finally, one of his half brothers made it up the ridge and begged him to join the fight. It has to be understood that the half brothers had long been among those who had mocked Antarah for his half-slave origin. But, of course, now the situation was desperate; they needed his help. “Sorry,” Antarah responded. “I’m a slave and a slave’s son. I’m not worthy to fight alongside you.” “Okay!” came the reply. “You’re free now! Please join us!”

Antarah waded into the fight and, as you might expect, routed the enemy. Eventually, his exploits in battle won him the epithet of “the Bedouin Achilles.”

But the story I’m really after is this one:

Some years later, another Arabian aristocrat, encountering Antarah, mocked him as a person lacking a distinguished lineage. By this time, though, Antarah had achieved renown both as a warrior and as a poet. And his response to the man mocking him is classic:

“You,” he told him, “represent the end of your noble line. I represent the beginning of mine.”

When the Sadducees and Pharisees came to John the Baptist, secure in the nobility of their descent, he told them “Think not to say within yourselves, We have Abraham to our father: for I say unto you, that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham” (Matthew 3:9).