John 17:6-19 — Year B — Easter

“Except the one destined to be lost.”

In that one tiny clause, Jesus attempts to explain away his failure, the one given to him but was lost.

The one that got away. Judas Iscariot. His betrayer. His disciple. His friend.

Earlier in John, Jesus had explained exactly what the will of God was — that he should lose nothing of all that was given to him. All. No exceptions.

But now, in his farewell discourse, with his betrayal at hand, Jesus revises and reinterprets God’s will for his life.

It’s not hard to understand where Jesus is coming from. He is at the end of his three years of ministry. He is heading towards his death and is offering final blessings, final commands, and and final comfort to his disciples.

He prays that they may be one in the midst of the fracturing of his community. Prayers for unity are never so fervent, it seems, and then when we are in the midst of breaking up.So it is not surprising that Jesus would see this one failure, the one person he could not or did not protect, and explain it ultimately as a matter destiny. Fate. Maybe even the will of God.

Of course, it is a different, or at least modified, will than the one he mentioned earlier in the gospel.

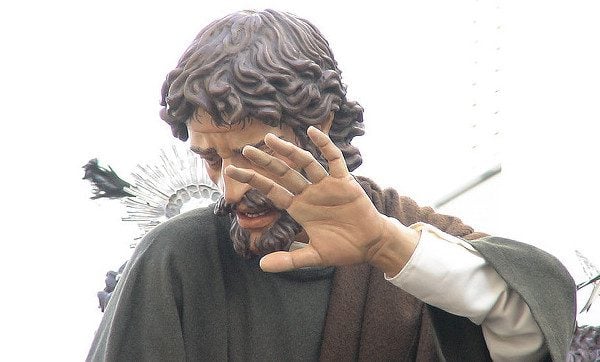

In essence, Jesus seems to be saying that it was inevitable. Perhaps this “one that got away” business represents the early Church’s wrestling with emerging theodicy, the question of why bad things happen to good people of God is Love.But if you listen closely, perhaps we can also hear the heartbreak of a man who will be betrayed by one of his closest friends. Perhaps we can also hear the disillusionment of a man who came to save the world but couldn’t even save all 12 of his closest friends.

There has to be sorrow. There has to be woundedness. It has to be that gut-wrenching emptiness when one’s highest and holiest expectations fall just short.

And here’s the thing, Jesus’ explanation for why this terrible thing happens is just as ineffective an explanation as our own for why bad things happen.

Apparently he was just as bad at theodicy as we are.

How fully human is that?

In a way it’s a relief, particularly when we look at our own fractured lives, streaked with unexplained tragedy. We can chalk it up to the will of God. We can seek some deeper explanation. But ultimately no explanation is satisfactory.

Does Jesus convince you?

Not me. But I am convinced he is hurting.

And that, honestly, is more convincing — and comforting — than any explanation he could have offered.