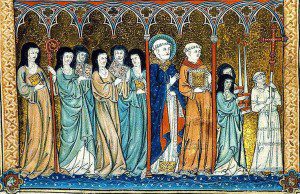

Some of our Friends of God shine like the sun, and their names are known even to an unbelieving world: Meister Eckhart, Henry Suso, Johannes Tauler, Jan Ruysbroeck. Some lie in forgotten corners of history like so many fallen autumn leaves blown into the shadows. Often, but not always, it’s the women who drift into anonymity. I’m happy to say, though, that that seems to be our problem more than it is one of the Friends of God, because all those famous men who represent the spiritual life in the 14th century had deep and dependent relationships with many female Friends of God.

Some of our Friends of God shine like the sun, and their names are known even to an unbelieving world: Meister Eckhart, Henry Suso, Johannes Tauler, Jan Ruysbroeck. Some lie in forgotten corners of history like so many fallen autumn leaves blown into the shadows. Often, but not always, it’s the women who drift into anonymity. I’m happy to say, though, that that seems to be our problem more than it is one of the Friends of God, because all those famous men who represent the spiritual life in the 14th century had deep and dependent relationships with many female Friends of God.

Here is a banal introductory comment or two: Gender relations can be prickly stuff, but the men-women quandary is not a new problem. It has been around, oh, say since the gates of Eden slammed on Adam’s and Eve’s backsides. It manifests in different ways over time. Today we hear all about the “war against women,” which, in this country, is beyond silly. Visit central Africa, and then we can talk about such a thing. The 14th century had its own versions of gender tensions.

Part of the tension lies in the radical affirmation that the way of Christ granted to women. According to Rodney Stark in The Rise of Christianity, this was one of the most compelling things about the gospel in the early church. Paul’s outrageous statement that in Christ there is neither male nor female described a wholly new community of persons defined primarily not by their human relationships or circumstances but by their relationships to one Center, Jesus Christ. I am a daughter and sister and wife and mother, but none of these things are who I really am. In Christ Jesus, I am a child of God through faith.

This teaching, however, was not toggle-switch effective. It wasn’t a light switch that turned on and banished darknesses. It was, like many of Christ’s teachings, a dimmer switch only slowly bringing light into dark corners. And the 14th century had many dark corners.

Gender relations in 14th-century Europe had their own dynamics, created in part by the wars-plagues-famines trifecta of misery. There just weren’t enough men to go around. The unremitting wars had reduced the male population, and the Church’s call to celibacy took any number of other potential husbands out of the picture. Women’s ability to generate their own income through crafts or trade was severely limited, and consequentially convents and Beguine communities filled with women.

I never would have made it as a 14th-century woman. I’m barely making it as a 21st-century woman. I’ve read about the conditions in a 19th-century convent in northern France—cold cells without heat, thin blankets, limited clothing, poor lighting, bland food—and I’m fairly miserable just thinking about it. What seems to have sustained many of these women is a venture into a unique and fertile combination of mysticism and piety, vision and holiness, ecstasy and virtue. Mysticism without piety can be hysterical, untenable, suspect; piety without mysticism can be harsh, dry, inert. Together, however, they created a sustaining rhythm that mitigated the severe realities of their living situations.

Meet Christina Ebner. When she was twelve years old, she entered Engelthal Convent in Nuremberg, and she lived there for the next sixty-seven years. Cultured, aristocratic, well-connected; ascetic, mystical, literate; prayerful, pious, and spiritually “contagious.” She offers one example of the political diversity among the Friends of God. She was pro-imperial in the conflicts of the day, whereas many of her spiritual peers were pro-papal. This, however, did not impede their spiritual friendship. In this day of increasing extremes, would that we could set aside our political proclivities and convictions for the sake of Christian unity. Imagine: In Christ there is neither Republican nor Democrat, conservative nor liberal…

Meet Margaretha Ebner (no relation to Christina), born c. 1291, and a member of the convent in Medingen. Her story stands out to me because she was, as Rufus Jones describes her, “not a person of much intellectual range…strongly emotional and sentimental, a victim of lifelong illness and plainly enough psychopathic.” Jones admits her “permanent contribution is meager.” And yet… Margaretha was a good friend of another who was a great “contributor” to the Friends of God, Henry of Nördlingen. Henry’s influence was both broad and deep as he served as a confessor, itinerant preacher, and prolific writer. He and Margaretha exchanged a vast correspondence, and these letters pass on to us an extensive vision of their times, their experiences of faith, and their visions. So, how good is it to be a Friend of God and a friend to a Friend of God? Margaretha, whose own stability was shaky and her scholarly prowess dubitable, “contributes” by sharing her life and stories with another, and listening to that other’s life and stories. I love that.

Meet Adelheid Langmann, another of the sisters in the Engelthal convent. Jones points out that her notability is attributed to her writing—Offenbarungen (Revelations)—which gave her a visibility that, he suggests, is unwarranted. Jones points out that history is an odd thing; it gives memory to those who record their thoughts or experiences, no matter how inconsequential those ideas are, yet there are always others whose thoughts and experiences are noteworthy but, unrecorded, are forgotten forever. Adelheid is famous for being notably forgettable. What a perfectly lovely kind of person to include in the community of God’s friends. What a travesty it would be if the Friends of God were a community “where all the women are strong, all the men are good looking, and all the children are above average.”

Lastly, meet Elsbet Stagel of Zurich, who, according to Jones, “had a trained and well-ordered mind, a seasoned and disciplined life.” Another historian once called her “a mirror of all virtues.” She “learned how to swim in the Life of God as an eagle swims in the air.” I want to be Elsbet when I grow up. (Living in Switzerland wouldn’t be bad, either.) Elsbet’s inner life comes to us as a rich account of prayer, the imitation of Jesus, and humble confidence in God, but it’s her storytelling that attracts me.

We have from Elsbet’s hand thirty-one biographies of her sisters, short vignettes of women of faith who are in pursuit of God’s friendship. The stories themselves are disconcerting because of their ugly (to us) accounts of self-torture in the conviction that suffering had value in itself. You’d think that the suffering of the 14th century was adequate to itself, but no, some of these women whipped themselves, some refused to enjoy the beauties of creation, some refused basic comforts like beds or hot food. But while we may feel these are unworthy examples of the spiritual life, we may still recognize Elsbet’s service to them, and to us, in telling their stories. For one of the signs of the Friends of God is that they were friends to one another, and Elsbet’s gift was her willingness to give her friends memory by listening to them and honoring their lives. Go to coffee with a friend, and simply listen to her story; ask him how he is pursuing Christ; be a Friend of God.

I do think some of the peculiarities of the women come down to us more forcefully than those of the men. Undoubtedly Meister Eckhart had his wierdnesses. Who doesn’t? But, gee, if you’re Meister Eckhart, who cares or even notices? If you’re a kooky nun, however, a lack of academic accomplishments might make your oddities more memorable.

The lovely, lovely thing is that God’s friends include the weird and the wonderful, the plain and the powerful, the ordinary and the extraordinary, the balanced and the imbalanced. In Christ we are all nothing but children of God.