Growing up there was a certain sort of Christian scientist who would blame Plato or Platonism for anti-science attitudes. Karl Giberson, by all accounts a fine scientist, blamed Plato, Platonism, or neo-Platonism for anti-science views of Christian leaders in “the dark ages.”

Growing up there was a certain sort of Christian scientist who would blame Plato or Platonism for anti-science attitudes. Karl Giberson, by all accounts a fine scientist, blamed Plato, Platonism, or neo-Platonism for anti-science views of Christian leaders in “the dark ages.”

Take this example from many:

We will look briefly at some of the important leaders of the Early Church and see how their particular worldviews were based on the Bible, interpreted within the context of the reigning philosophical perspective, which was an otherworldly, non-scientific school of thought that had originated centuries earlier with Plato.*

If there was ever a philosopher more interested in living well in this world than Plato, I am not sure who that philosopher would be. Most of his dialogs are intent on teaching us to live an examined and good life now. Since Plato did not believe we could escape the world we see (the world of Becoming), Plato was eager to understand that world as it is.

Giberson, however, exemplifies another common mistake when reading Plato:

Furthermore Augustine took his lead from Plato, who had taught that our limited (Augustine would say fallen) senses were inadequate to discover truth. It seemed safer to place one’s trust in the authority of Scripture rather than in the philosophies of men.**

Of course, Giberson must admit that Plato did write a work trying to explain the world we see: Timaeus. In fact, Timaeus was one of the few works to survive in the West and so for most of the Middle Ages (mostly not dark!), Plato was known as a cosmologist. What was the result?

Plato had a sophisticated philosophy of science that did not depend on finding The Truth, but finding the most likely story. He did not think that humankind would get a final explanation of everything and so encouraged theorizing! In fact, his Timaeus is a first draft on such a theory. He also put a primary emphasis on mathematics and mathematic modeling. In Timaeus he says:

Let us now assign to fire, earth, water, and air the structures that have just been given their formations in our speech. To earth let us give the cube, because of the four kinds of bodies earth is [e] the most immobile and the most pliable— which is what the solid whose faces are the most secure must of necessity turn out to be, more so than the others. Now of the [right-angled] triangles we originally postulated, the face belonging to those that have equal sides has a greater natural stability than that belonging to triangles that have unequal sides, and the surface that is composed of the two triangles, the equilateral quadrangle [the square], holds its position with greater stability than does the equilateral triangle, both in their parts and as wholes. Hence, if we assign this solid [56] figure to earth, we are preserving our “likely account.” And of the solid figures that are left, we shall next assign the least mobile of them to water, to fire the most mobile, and to air the one in between. This means that the tiniest body belongs to fire, the largest to water, and the intermediate one to air— and also that the body with the sharpest edges belongs to fire, the next sharpest to air, and the third sharpest to water. Now in all these cases the body that has the fewest faces is of necessity the most mobile, in that it, more than any other, has edges that are the sharpest and [b] best fit for cutting in every direction. It is also the lightest, in that it is made up of the least number of identical parts. The second body ranks second in having these same properties, and the third ranks third. So let us follow our account, which is not only likely but also correct, and take the solid form of the pyramid that we saw constructed as the element or the seed of fire. And let us say that the second form in order of generation is that of air, and the third that of water.***

If such early mathematical modeling looks crude today, it was still to have good fruit. Why? First, math mattered to science. Math was real and the world was slippery. If you could not do math, Plato did not want you to opine in his school. (Modern biologists should take note.) Second, the Platonic solids were assigned roles that made empirical sense given the four elements (fire, earth, air, water): fire is “cutting” and so associated with the tetrahedron. Earth can fill Euclidean space without gaps (it is the most solid of solids) and so associated with a cube. Water is hard to hold and so is a icosahedron. Finally, the cosmos is as close to a perfect sphere as possible and so is the solid shape that fills a sphere the most: the dodecahedron.

The relationship of the dodecahedron to the cosmos is a good example of what Plato was trying to say about science in Timaeus. Plato argues that the sphere is the “perfect shape,” but he suggests that the closest the cosmos can get is the dodecahedron. Just as music (incarnate math!) is almost mathematically perfect, so the dodecahedron almost fills the sphere. Our models (the best we can do) and changing reality (influenced by errors in the observer and in instruments) make perfect harmony in the model (final Truth) impossible.

Obviously, both the models and the maths Plato suggested in Timaeus were first drafts and needed work, but the revolutionary idea was there: science and mathematic modeling go together. The model may not find unchanging truth, but should capture the appearance as much as possible. The scientific revolution was born when Platonist and Christian scholars like Kepler applied Christian Platonism and good math to the natural world.

Science was born when Platonism’s love of math met the Incarnation. The Incarnation allowed Aristotle and his love of experimentation in the natural world and collecting of natural data to appeal to the educated!****

I think scientists, even Christian scientists like Giberson, are disturbed by Platonism because it puts a check on science and the illusions of scientists to finding Truth. Platonism recognizes that reality is complex. The real world is technically the eternal, unchanging world: not the world we see. The moment this is said, the scientists assume (quite falsely) that Plato must deny the importance of studying the world in which we live (the “world of Becoming”). After all, if the Becoming world is less than the real world (pure Being), then why bother?

This logical error infects scientists to this day. Of course, it is important to deal with ideas and being, including God, but humankind lives in the world of Becoming. It is true that some neo-Platonists would argue that studying the natural world was unimportant, but they did not prevail in Christendom. God had, after all, said His creation was good. God had become flesh in the person of Jesus Christ.

No Christian can say “matter is evil.” In fact, Plato did not think matter was “evil” either.*****

Instead, the Christian can theorize (tell likely stories) about the natural world and not worry too much that the stories might bump into Truth (as revealed in logic, math, and Revelation). We can expect some tension between what is and what is becoming. This sophisticated philosophy of science and knowledge can hold ideas in tension as we work out what is the “likely story” that explains how pure ideas and changing matter relate.

This is good news and it means we can follow the evidence where it leads without constant epistemological crisis or the crude “conflict” thesis of street atheism or folk Christianity. Instead, we can use the best story we have in science, even one we have reason to think will turn out to be false, while looking for alternatives. If the best story of science is that the cosmos is “old,” then we use that account when we do science. On the other hand, there are theological and philosophical reasons to wonder if that story is the best possible account of reality so we can be open to some scientists pursuing a different account.

We must never assert that our speculations are the best theory, but on the other hand, demand the right to speculate in the world of Becoming! Science moves toward Truth, but it will never (if Platonism is correct) find final truth. That job is left to logicians, mathematicians, and theologians . . . . though here too human frailty makes the Platonist and the Christian dubious that we will ever embrace only the Truth, the whole Truth, and nothing but the Truth this side of Paradise.

—————-

*Giberson, Karl (2011-01-01). Worlds Apart: The Unholy War Between Religion and Science (Kindle Locations 685-687). The House Studio. Kindle Edition.

**Giberson, Karl (2011-01-01). Worlds Apart: The Unholy War Between Religion and Science (Kindle Locations 725-727). The House Studio. Kindle Edition.

***Plato (2000-03-15). Timaeus (Hackett Classics) (pp. 47-48). Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

I have written more technically on Timaeus. I have also tried to introduce Greek thought to lay readers, especially Plato.

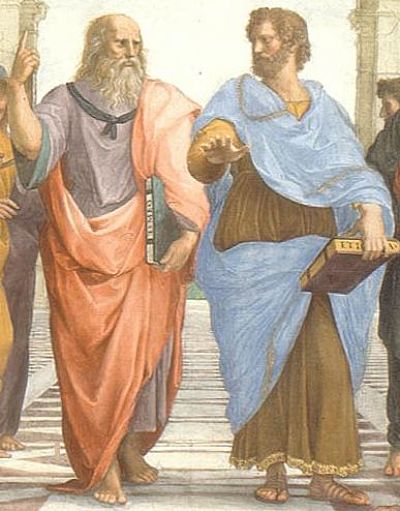

****Aristotle and Plato are too often presented as opposites. See AE Taylor for a scholar who shows that they had more in common than not. The “School of Athens” painting deceives some with Plato pointing up and Aristotle pointing down showing a difference; however, note that they are side by side and together covering all of reality!

*****In Phaedo, Socrates is presented as comforting his students regarding his death. He has some extreme language about the “body.” Note, however, in Timaeus that Socrates is just exchanging one body for another! He is moving on up!

This is the devotional portion of a lecture to The College at The Saint Constantine School.