Imagine education designed to put you in chains. Plato described it (Republic VII) and Carter G. Woodson fought it and knew in part how to defeat it. Racism in America (within my own lifetime) was a central feature of the academic curriculum in government schools.

Imagine education designed to put you in chains. Plato described it (Republic VII) and Carter G. Woodson fought it and knew in part how to defeat it. Racism in America (within my own lifetime) was a central feature of the academic curriculum in government schools.

This has not ended.

In my own career, I have seen excellent faculty denigrated and ultimately let go, because they were too “black.” If you have not, pause. Think. We have made great strides over the last one hundred and fifty years. Slavery is dead and it surely does matter if your legal status is free and not enslaved, but if you go to schools where you are viewed as a servant, then you must also reject that paradigm.

This is hard for a child to do.

I am a conservative, because conservatives taught me that ideas are the property of all thinking persons. Nobody should be privileged when it comes to thinking or information. The good fruit of human achievement belongs to us all. If you hear that Africans had magificent empires, as they did, and great Christian thought, as they always have, then all Christian persons are eager to learn of this! I long to drink more deeply of the wisdom of Ethiopian Christians that has been kept from me by racism, yet also by the sheer amount of wonderful books the world contains! I cannot know one thing well (say Plato) let alone all the marvels of the earth.

Heaven is so we can learn from everyone forever.

The content of education can never be inclusive enough, something great is always missing, but it can whet our appetite for the infinite banquet and make us ready to partake.

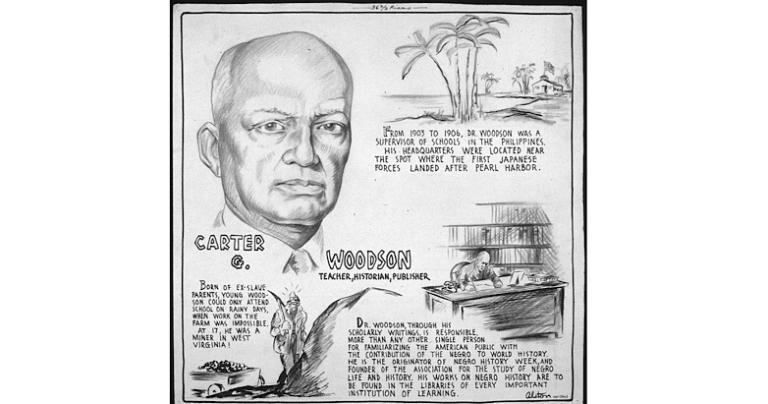

The insightful educator Carter G. Woodson wrote a must-read on education that applied to the centuries of mis-education of the African-American in America. This book must first be used to rectify this crime, but it also reveals the way an establishment keeps a minority (or majority that has ‘bad’ views) under control. I have collected some ideas from this important book, made a few comments, but mostly present them so I can continue to think about them.

Think of this as my notes on improving education for all God’s children after listening to Dr. Woodson.

Dr. Woodson captures the nature of education:

The mere imparting of information is not education. Above all things, the effort must result in making a man think and do for himself just as the Jews have done in spite of universal persecution.

We cannot think for ourselves by being slaves to the past, using great books as a dead hand on our shoulder from the past keeping us from progress, or as slaves to the future, viewing the “arc of history” as a weird force that makes what is new always better than what is old.

Dr. Woodson comments:

If Negro* institutions are to be as efficient as those for the whites in the South the same high standard for the educators to direct them should be maintained. Negro schools cannot go forward with such a load of inefficiency and especially when the white presidents of these institutions are often less scholarly than Negroes who have to serve under them.

Early in reading Woodson, the sneaky (not quite acceptable) thought occurs: “What if desegregation came and so ‘white’ leaders desegregated schools by making poor white schools like those of African-Americans?”

This fits so many evils of our time together. Yet one must never forget the evil began in slavery, racism, and schools designed to keep African-Americans in a subordinate position. If this mis-education was given to others, then the problem grew, but the origins of bad institutional, corrupt state education was in the mistreatment of the African-American student.

End it.

What should we replace mis-education with?

Real education means to inspire people to live more abundantly, to learn to begin with life as they find it and make it better, but the instruction so far given Negroes in colleges and universities has worked to the contrary. In most cases such graduates have merely increased the number of malcontents who offer no program for changing the undesirable conditions about which they complain. One should rely upon protest only when it is supported by a constructive program.

Dr. Woodson understands that true education is not just so I can do better, but so everyone can prosper. We must not use our education so we win while others lose. This is not the Christian way. In fact, the devils rely on words to enslave us to sin, to training, to giving us a slave mentality. Everywhere African-Americans were born free, but education was designed, even in “progressives” like Dewey, to enslave.

When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions.

This is a great book, one I must continue to process, but Woodon’s picture of the development of classical Western philosophy is flawed. He says:

To begin with, theology is of pagan origin. Albert Magnus and Thomas Aquinas worked out the first system of it by applying to religious discussion the logic of Aristotle, a pagan philosopher, who believed neither in the creation of the world nor the immortality of the soul.

This is just not true and not true in a way that ignores Eastern and African contribution to systematic theology. Whether in Alexandria or in Syria, the East had great doctors of the church long before Albert and Thomas. Even in the case of Thomas, Aristotle was just one influence. Plato, who did believe in the creation of the world and the human soul, and his disciples are frequently cited and influential in Thomas.

However, just as Nancy Pearcey’s main point in her newest book should not be missed because of a flawed history of philosophy, so this flawed generalization can be discarded to understand the central message of Dr. Woodson. We do not benefit by reading even brilliant people without the very inquisitive spirit that Woodson is encouraging!

Woodson is critical of schools of theology thrown up more to build the careers of the administration than the Kingdom of God. Much of this criticism could be applied to Christian colleges today with their multiplication of schools of theology and seminary programs:

No teacher in one of these schools has advanced a single thought which has become a working principle in Christendom, and not one of these centres is worthy of the name of a school of theology. If one would bring together all of the teachers in such schools and carefully sift them he would not find in the whole group a sufficient number qualified to conduct one accredited school of religion. The large majority of them are engaged in imparting to the youth worn-out theories of the ignorant oppressor.

The situation is somewhat better than in Woodson’s day, particular in the historical African-American colleges. Scholarly levels are improved, but Woodson wishes for more:

This minister had given no attention to the religious background of the Negroes to whom he was trying to preach. He knew nothing of their spiritual endowment and their religious experience as influenced by their traditions and environment in which the religion of the Negro has developed and expressed itself. He did not seem to know anything about their present situation. These honest people, therefore, knew nothing additional when he had finished his discourse. As one communicant pointed out, their wants had not been supplied, and they wondered where they might go to hear a word which had some bearing upon the life which they had to live.

Woodson is arguing for relevance. He also wishes for a dialog between what has been learned in schools and the experience of people. What Woodson calls “advanced ideas” should enter into a dialectic with study of what the lived experience of the people of God (African-American) can teach the educated. There is enough in this own observation to fill volumes.

Today’s popular culture will be, in part, the cultural heritage studied in schools tomorrow. The largest part of popular culture is not good and needs the leaven of “advanced ideas.” This is a dialog and we will never quite get it right, but it begins with trying. The educated must look for embryonic beauty and the informally educated should know the limits of training based only on personal experience.

Perhaps most critically, Woodson reminds us that much of what Americans defend as “traditional” morality was inapplicable without the servitude of African Americans. Women of color rarely had the luxury of the “stay at home Mom” household. (Of course, families like my own in Appalachia shared this experience to an extent. However, we were not kept down in the organized manner of African-Americans). Vitally, since much of “traditional” morality could not exist without enslaved labor or racism, that morality was shot through with hypocrisy. You cannot love your neighbor as yourself if you view your neighbor as sub-human and an object of exploitation.

Woodson:

The American Negroes’ ideas of morality, too, were borrowed from their owners. The Negroes could not be expected to raise a higher standard than their aristocratic governing class that teemed with sin and vice. This corrupt state of things did not easily pass away. The Negroes have never seen any striking examples among the whites to help them in matters of religion. Even during the colonial period the whites claimed that their ministers sent to the colonies by the Anglican Church, the progenitor of the Protestant Episcopal Church in America, were a degenerate class that exploited the people for money to waste it in racing horses and drinking liquor. Some of these ministers were known to have illicit relations with women and, therefore, winked at the sins of the officers of their churches, who sold their own offspring by slave women.

True family values, a vital part of the Christian message, cannot be constantly maintained in a racist society:

Some years later when the author was serving his six years’ apprenticeship in the West Virginia coal mines he found at Nutallburg a very faithful vestryman of the white Episcopal Church at that point. He was one of the most devout from the point of view of his co-workers. Yet, privately, this man boasted of having participated in that most brutal lynching of the four Negroes who thus met their doom at the hands of an angry mob in Clifton Forge, Virginia, in 1892.

Racism is present in education even when positive stereotypes shape a curriculum:

The small number of Negro colleges and universities which undertake the training of the Negro in music is further evidence of the belief that the Negro is all but perfect in this field and should direct his attention to the traditional curricula.

My own mother heard such sentiments expressed in church people who viewed themselves as progressive.

Instead of falsehoods, positive or negative, true education treats people as people. Recently, I heard of a s0-called classical school intent on telling students what to make of each great work of literature. They wanted to get the right ideas into the heads of the students. This is not education, but a horrific imitation of enslaving propaganda. Woodson saw it at work in the education of African-Americans:

In fact, the keynote in the education of the Negro has been to do what he is told to do. Any Negro who has learned to do this is well prepared to function in the American social order as others would have him with the few political positions earmarked as “Negro jobs” and to crush those who clamor for more recognition.

As a Christian, Woodson reminds all of us that the goal of Christain education must be to train servants of the people and not leaders:

The servant of the people, unlike the leader, is not on a high horse elevated above the people and trying to carry them to some designated point to which he would like to go for his own advantage. The servant of the people is down among them, living as they live, doing what they do and enjoying what they enjoy. He may be a little better informed than some other members of the group; it may be that he has had some experience that they have not had, but in spite of this advantage he should have more humility than those whom he serves, for we are told that “Whosoever is greatest among you, let him be your servant.”

The servant of the people is the educator who liberates the man. The enslaver drills and kills:

Such has been the education of Negroes. They have been taught facts of history, but have never learned to think.

Woodson reminds those of us in the “classical” education movement that we must never be reactionary. We are not looking backwards, because there is no golden age to which we can return. Especially in America for African-Americans, we must have what the Bible calls a progressive vision. We hold to eternal truths, but we keep learning how to apply them better.

In this particular respect “Negro education” is a failure, and disastrously so, because in its present predicament the race is especially in need of vision and invention to give humanity something new. The world does not want and will never have the heroes and heroines of the past. What this age needs is an enlightened youth not to undertake the tasks like theirs but to imbibe the spirit of these great men and answer the present call of duty with equal nobleness of soul.

Negroes do not need some one to guide them to what persons of another race have developed. They must be taught to think and develop something for themselves.

This idea is essential to the education I have been taught and which I try to establish in our school. We do not build around a curriculum or merely ape old masters. We pick books and media that help us follow the pattern of discussion that leads to thinking and developing something for the community in which the student lives.

We think for ourselves or we do not think. We must not imitate, not even so great a thinker as Plato, because if Plato is not setting us free to think new thoughts, then we are not reading Plato, but are gazing at the Platonic corpus. Give that corpus a funeral and read with all the heart, soul, and mind. While we must attend to politics, because we are human, we must not be political before we are human!

Our education should begin by making us free human beings.

The New Negro in politics, moreover, must not be a politician. He must be a man.

Education should bring soul liberty. Let’s make sure it does.

Read Dr. Woodson.

————————

*Dr. Woodson is using the term for African-Americans current when he was writing. I have not changed it. His argument was:

It does not matter so much what the thing is called as what the thing is. The Negro would not cease to be what he is by calling him something else; but, if he will struggle and make something of himself and contribute to modern culture, the world will learn to look upon him as an American rather than as one of an undeveloped element of the population. The word Negro or black is used in referring to this particular element because most persons of native African descent approach this color. The term does not imply that every Negro is black; and the word white does not mean that every white man is actually white. Negroes may be colored, but many Caucasians are scientifically classified as colored. We are not all Africans, moreover, because many of us were not born in Africa; and we are not all Afro-Americans, because few of us are natives of Africa transplanted to America. There is nothing to be gained by running away from the name. The names of practically all races and nations at times have connoted insignificance and low social status. Angles and Saxons, once the slaves of Romans, experienced this; and even the name of the Greek for a while meant no more than this to these conquerors of the world. The people who bore these names, however, have made them grand and illustrious. The Negro must learn to do the same.