In a recent post about why Evangelical Christianity doesn’t make you a better person, Neil Carter wrote the following:

Evangelical Christianity Has Messed Up Priorities

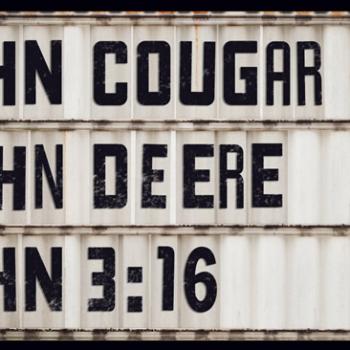

The evangelical Christian vision of heaven is based on right belief, not on right behavior. For evangelicals, it’s not the loving, caring, hard-working people of the world who get into heaven. I mean, sure, the people who get there may or may not possess those qualities, but good character isn’t what gets you in. You have to believe the right things, which is to say your theology must match evangelical theology on at least a handful of key doctrines which you can find on the back of any Billy Graham tract. Showing people love doesn’t get you in, but believing the “plan of salvation” does.

Consequently, evangelical culture rewards right belief over right character because in the end that’s what determines your eternal destiny. According to them, heaven will be filled with all kinds of unsavory characters who converted to the right theology before they died, while hell will be full of good, ethical non-believers. Because right belief tops their priority list, that’s what gets rewarded the most. Good behavior is nice, but it’s not the most important thing. Loving people matters, too, but even that seems to be reserved most for people who are already inside the fold. Loving people who are outside of it gets expressed primarily in invitations to become one of them. People on the outside must be willing to join the group if they really want to enjoy the full benefits because that’s the example that Yahweh set for them (depending on which verses you read, of course). That’s why evangelical Christianity fails to produce better people than any other ideologies. They reserve their highest rewards for things that frankly have little bearing on a person’s ability to love and accept other people.

One could even argue that this kind of exclusionary theology makes it harder for people to be accepting of others who are different from them. I’ve seen it happen time and time again. I’ll admit that the church can be very good at caring for its own, but once you find yourself on the outside of their tribe, even their acts of charity seem laced with an expectation that the gift you are receiving is intended to convince you that you must become like them if you want to be fully accepted. They naturally recoil at this charge, but think about it: What message would unconditional acceptance send to those who they believe must change or be punished forever? Can people’s kindness exceed that of the object of their worship? If God isn’t really going to accept those people as they are, why would the church?

Click through to read more. On the same theme, Tony Campolo recently wrote an article about his humanist son, whose concern for what is right often puts his parents, and of other Christians, to shame.

I am in two minds about this, because after my own conversion to Evangelical Christianity, I did both – I became one of those obnoxious, misguided people who thought that telling others “four things God wants you to know” was what it meant to love/evangelize them. But I also started volunteering at a soup kitchen, became more forgiving, and changed in other ways which I think would be considered an improvement from any perspective.

And so I think that the answer can be yes and no – and perhaps that is because Christianity is a path, and we often don’t understand fully where it is supposed to lead us when we begin on it. I suspect that is as true of other paths as of Evangelicalism.

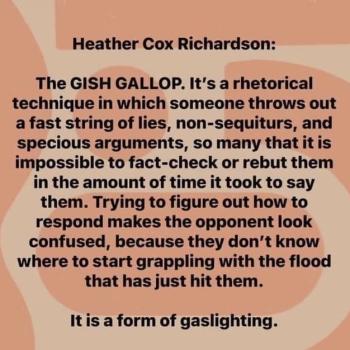

Sojourners recently had an article about Christians loving their religion more than God. That is something which can happen easily when we have had a life-changing epiphany. And again, it isn’t unique to Evangelicalism or even Christianity. An atheist who has discovered reason may not realize they are being a cheerleader for their side, and not fully embracing reason in many instances. We confuse our new worldview, which answers some questions that our previous worldview did not answer, and neglect to see that it too has shortcomings and is at best an approximation of the truth.

This also has to do with the view that Evangelicalism, Christianity, or any other worldview are about providing answers and ending our confusion. Randal Rauser had a nice post addressing an interview Lee Strobel gave, which talked about this, and ended with this prayer: “May God deliver us from the drive for superficial clarity, confidence and certainty that obscures our deeper confusion.”

The big epiphany is when we come to realize that fighting over who is right, and even dogmatically insisting that it is “us,” is itself an indication that we are just beginning on the path towards truth – because the truth is that people matter more than concepts and dogmas. And ironically, that is affirmed by most of the worldviews that people argue and fight and even kill one another over.

And so my answer to the question in the title of this post is that it can – if one does not remain stagnant and immature as a cheerleader for its ideas, but grows in maturity, and discovers the things which, even according to the key sources of that tradition, really matter most. And the same can be said if the question is asked about any other worldview, ideology, or tradition.

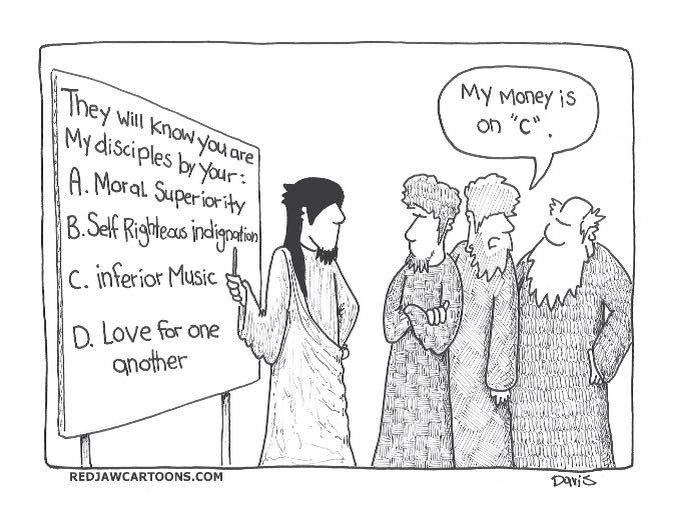

Of related interest, see also the New Humanist article on religion as a cause of violence, Jesse Dooley’s post about whether fundamentalists own Christianity, and Pete Enns’ post on why so many young people are giving up on the Bible and their faith. And finally, here’s a cartoon from Tim Davis that seems relevant: