Bill Hamblin has done a great service in providing a detailed outsider’s critique, repeating some of the frequent objections to the Documentary Hypothesis that gives us a chance to discuss and hopefully to reach greater clarity on the issue. Since Hamblin has shut down and deleted comments for anyone whose names don’t seem real enough to him, and (more important) since his 20-part attempted takedown of the Documentary Hypothesis (the theory that the first 5 books of the OT are the result of the combination of 4 independent documents) is too unwieldy to treat all at once on his blog, I thought I could summarize the points here and treat it as a whole while providing an open forum where all of Jupiter’s children who behave themselves are welcome to participate—even, and especially, Bill Hamblin (if that is even his real name).

Bill Hamblin has done a great service in providing a detailed outsider’s critique, repeating some of the frequent objections to the Documentary Hypothesis that gives us a chance to discuss and hopefully to reach greater clarity on the issue. Since Hamblin has shut down and deleted comments for anyone whose names don’t seem real enough to him, and (more important) since his 20-part attempted takedown of the Documentary Hypothesis (the theory that the first 5 books of the OT are the result of the combination of 4 independent documents) is too unwieldy to treat all at once on his blog, I thought I could summarize the points here and treat it as a whole while providing an open forum where all of Jupiter’s children who behave themselves are welcome to participate—even, and especially, Bill Hamblin (if that is even his real name).

I will also reiterate here my invitation to host a roundtable looking at specific texts so that we are not just sending volleys of assertions about what the theory is and isn’t or does or doesn’t claim. Of course, anyone remotely interested in this topic should consult first Joel Baden’s excellent and eminently readable The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis (Yale 2012), which does both of these things, giving an overview of the method and then walking the reader through specific texts to illustrate it. One can see similar ideas treated here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

First off, I think there have been some misunderstandings about what the DH is, which have led to some of Bill’s attacks, and I will try to clear those up. Even with these clarified I imagine Bill and I will still disagree, but it might get us closer to a conversation about key issues instead of red herrings. Below I try to summarize Bill’s posts in a couple of sentences and then react to each claim. There are so far 20 posts, so this will be an inordinately long treatment to digest in one sitting. For those sane ones of you who don’t want to wade through each post and reaction, I will summarize my critique here (for details on any one of these, see the individual treatments below the general summary):

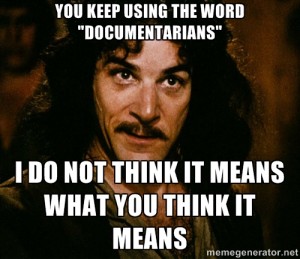

1) Hamblin does not seem to be familiar with the basic definition of the DH nor with the practice of source criticism given his preoccupation with authorship and empirical validation. (To be fair to him, his dogged focus on authorship may be due to his engagement with Bokovoy’s book, but I’m not sure. If this is the case, I should point out that Bokovoy’s book is not a work of Documentary analysis; it is a religio-historical use of Documentary analysis.) At the very least, Hamblin seems to understand “Documentarian” as any scholar who denies the singular Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch. Rather, the DH is, simply put, the hypothesis that the first 5 books of the Bible were woven together from four (4) originally independent sources, which themselves told the overarching story of the people of Israel. It is an attempt to solve the very particular problems exhibited in the first 5 books. Within that there is certainly debate and argument about how that took place, but I think neo-documentarians are converging on consensus. Hamblin’s confusion is most apparent in post #17.

2) He consistently misrepresents the methodology and treats results of analysis as if they were presuppositions and assumptions. (I do not think this is an attempt at deception, however. I think it is a genuine misunderstanding.) He seems to think that biblical scholars invented the idea of different authors and went looking for texts to prove their theory, all because they can’t admit that Moses himself was probably the author or at least originator of all these texts. Thus many if not most of these points are not really about the DH at all, but about the damage that the results of source analysis did to traditional claims of authorship. Put another way, even if we admitted every single one of Hamblin’s points, the DH wouldn’t change at all because he hasn’t dealt with what the DH is or how exactly scholars have come to the conclusions that he is so skeptical of. What every careful reader of the Bible has agreed on in the past 2 millennia is that the text has problems. Where they differ is in their solutions to the textual problems. The Documentary Hypothesis arose out of a careful reading of the text and an attempt to solve those problems. It is not the result of the application of some invented literary theory that can be applied to any text—it is a direct result of the need to address major narrative issues. This cannot be emphasized enough.

3) It strikes me after having read all these posts is that Hamblin’s beef isn’t really with the DH at all, but rather with the general historical assessments of Biblical Studies, which is duly skeptical about things like Mosaic authorship and historicity. This is not strictly speaking a concern of the DH, but it is widely held in the field. So when he talks about anachronisms, he’s speaking not to Documentarians (for whom anachronisms are mostly uninteresting on their own) but to biblical historians. Those historians might make use of the results of the DH, but they are making claims that mostly fall outside its purview.

I try to summarize each of his posts fairly and dispassionately and then, in brackets, offer a (sometimes impassioned) reaction, mostly so that anyone wanting a reaction to any of the individual posts can get it here, since I and other knowledgeable people can’t comment on his site:

DH 1: The Documentary Hypothesis

Hamblin sets forth his definition of the DH: “that the first five books of Moses… were not written by Moses, but were composed later by unknown editors/redactors out of preexisting texts, textual fragments, and oral traditions.”

[And here we’re off to a bad start; as I noted on his site, this is not a proper definition of the DH. It is that four originally mostly independent documents were interwoven to give us the first 5 books of the Hebrew Bible. The DH has virtually nothing to say about the pre-existing texts or oral traditions that made up the documents themselves. Think of someone taking the 4 gospels and weaving them into one grand narrative. The DH attempts to uncover those documents (hence the name), not the traditions that made up the individual gospels. There are other types of criticism that address pre-existing fragments and oral traditions (i.e., form criticism, tradition criticism, etc.). What this reveals is Hamblin’s preoccupation with authorship, which muddies his understanding of how source criticism is done and speaks volumes about his priorities. To be sure, this is also a preoccupation of Bokovoy’s, which is likely why Hamblin is exercised about it. But I can’t reiterate strongly enough that the DH proper is an effort to make literary sense of the penultimate stage of the text, not to come to a definitive understanding of some hypothesized author. It is to solve the problem of why the text before us is so garbled. Hamblin never treats this raison d’etre of the DH once in his whole series!]

Hamblin interprets a variety of biblical passages (OT and NT!) to make the claim that the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch “was assumed by nearly all biblical authors”(!). He claims the clearest example is Deut 31:24-26, which says that Moses wrote “this law”, though he says it probably just refers to the book of Deuteronomy.

[Once again, this is a puzzling place to start discussion of the Documentary Hypothesis. But to his points, there is no clear evidence that any biblical author thought Moses wrote the first 5 books. Hamblin deleted my attempt to point out that in the Bible the Hebrew word Torah doesn’t refer to the first five books (as it would come to later), but rather to “instruction” or “teaching”. So when Deut or Ezra or Paul refer to the torat-Moshe, they’re referring to the instructions delivered by Moses, the body of legal material in parts of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, or Deuteronomy. The texts that speak of Moses do so in an exceedingly limited way, and always about writing down the instructions given by God, not the whole story of the Israelites from Genesis to Deuteronomy. I’ll say it again, there is no biblical author that demonstrably says he thought Moses wrote the Pentateuch as we now have it. The burden of proof is on Hamblin’s camp.]

Hamblin links to two reviews of Bokovoy’s book in the Interpreter, one by a promising young undergraduate in Biblical Studies and the other by an interested student of the bible without formal training so far as I can tell. Both reviews are generally positive and even-handed.

DH 4: Ancient Concepts of Authorship

Hamblin asserts that it is rare that the originators of ancient teachings wrote them down (think Socrates/Plato or even Jeremiah/Baruch), and this fact should be remembered by source critics, who say Moses didn’t write the Pentateuch.

[The purpose of the DH is not to make claims about authors. Its purpose is to make sense of problems in straightforward readings of texts. Claims about authors only follow the separation of texts, so I’m not sure that this point is relevant at all to the division of the texts into sources. In other words, how exactly would it affect the DH to remember that teachings often originated with people who didn’t write them down? The DH argues there are 4 documents, not non-Mosaic authorship per se. That is a conclusion of the result of the documentary analysis, it is not its target!]

DH 5: Tradition and Authorship

Extending point 4, Hamblin reiterates that ancients understood authorship differently from moderns, and that “a fundamental assumption of the Documentarians—those who support the Documentary Hypothesis—on the other hand, is that the scribes are the “real” authors of the biblical texts.”

[At this point I’m not sure whether he has read actual “documentarian” analysis, because this is not assumed by any source critic I am aware of, living or dead. Again with the authorship!]

Hamblin reminds us that scrolls and books are not the same thing. “The ancient decisions regarding the physical division or combination of texts into scrolls/books often was only marginally related to questions of authorship.”

[What this has to do with the practice of source criticism escapes me.]

Hamblin points out that just because everyone agrees that there are lost books (e.g., Jasher), doesn’t mean that Documentarians can go around finding hidden books therein. He also first broaches the subject of “vehement” disagreement among Documentarians “over the specifics of what exactly the Documentary Hypothesis really means.”

[Once again, I am aware of no single biblical scholar who makes the claim that they are finding lost books like the ones mentioned in Kings as a basis for source analysis. As for the problem of disagreement among “documentarians” there really isn’t that much vehement disagreement among documentarians properly speaking. The vehemence that he is referring to is between documentarians and non-documentarians, i.e., those who say there aren’t 4 documents. I’ll treat this more below.]

Hamblin admits that multiple authorial hands had to have been at work in the Pentateuch, since it narrates Moses’ death and burial and it has many “to this day” phrases that presuppose a time long after Moses. He seems to understand this to have been a light retouching over top of a fundamentally Mosaic text. He concludes that “documentarians should note that such editorial comments would not be necessary unless the authors/tradents/editors/copyists/redactors were drawing on ancient documents or, minimally, ancient oral traditions that the editors themselves realize are already archaic to their contemporary audience.”

[“To this day” phrases, like Moses’ death, have nothing to do with the isolation of sources. They did serve to warm people up to the idea that the traditional view of Moses as author was not quite accurate, but they did not form the basis of the isolation of sources. Documentarians don’t need to note anything about what this says about scribes drawing on ancient documents, because these items are not criteria for the analysis!]

DH 9: Dating Ancient Texts pt. 1

Hamblin spells out the ways scholars date ancient texts, which almost never have a copyright on the title page: examining 1) explicit references to dates in the texts, 2) synchronisms between the Bible and dates known from stuff outside it, like Pharaoh Sheshonq, and 3) the last dated event described in the text.

[The Pentateuch contains virtually none of these compared with Samuel-Kings, and when it does, it usually points much later. In any case, this has nothing to do with the Documentary Hypothesis. In fact, it is rather the other way round. The first full-blown exposition of what we call the Documentary Hypothesis today was put forth by Julius Wellhausen in the 19th century. It wasn’t what Wellhausen initially set out to do. What he wanted to do was to write a history of ancient Israel, but he realized he couldn’t do that without making sense of the texts. So he set about doing that and, drawing on earlier work that recognized sources in the Pentateuch, set forth his division of the sources. After the sources were divided he then set about making chronological sense of them as a way of talking about the broader history of ancient Israel. This is why his seminal work is called Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels, because it’s the stuff to be dealt with before we can talk about history! This is the textual work, in other words, that allows historical conclusions to be drawn. Hamblin has put the cart before the horse.]

DH 10: Dating Ancient Texts pt. 2

Hamblin’s fourth point about dating relates to anachronisms (like saying Caesar conquered France, a modern term, when it was in fact called Gaul in his time). “Documentarians often posit that chronological data, specific dates, or historical allusions in a text do not necessarily reflect the original date of the text, but could have been inserted at a later date in the process of editing and redaction. As many scholars have noticed, this creates a major methodological problem for the Documentary Hypothesis.”

[It would only create a methodological problem if it were part of the methodology, which it is not! Dating is done by biblical scholars in general, documentarian or not, but is not the basis for claims about the division of the sources. This has no bearing on the working out of the Documentary Hypothesis, only on the conclusions drawn therefrom. Again, such anachronisms served to warm people up to the idea that the text isn’t as old as tradition says, but anachronisms themselves contribute nothing to the isolation of separate sources. It’s the other way round. Documentarians only care about the relative dating of the texts to each other, and as far as these source analysts care, it could have been done before Moses or yesterday. That is, it matters a great deal to the source division to say whether D knew J and J knew P, but absolute dates do not. They could have been written days apart from each other; all that matters to the DH is relative literary sequence.]

As an addendum to posts 9 and 10 Hamblin speaks of the problem of true prophecy. He makes no claim as to what this has to do with the DH, and for good reason, because it doesn’t relate directly. See my surviving comment there for detailed reaction to these points.

Hamblin argues that there is no empirical evidence for the DH, which for him means “manuscript evidence”. He discusses the Septuagint evidence before moving on to Genesis 1 and 2, where he claims that the dual name Yahweh Elohim disproves the hypothesis, which reveals he apparently assumes that name division = source division. He concludes “Either way, it is important to recognize that when we examine the actual variant ancient empirical textual evidence for the alleged distinction between an Elohist chapter 1, and a Yahwist chapter 2, the hypothesis fails.”

[12 posts in, and even though we have yet to see an accurate description of the DH, we finally get to a text. This is maybe where I have most to say, and for more detail see my surviving comment there. Also, David B correctly reacts in detail to the Yahweh-Elohim problem. This is the most bewildering of posts, because it seems to assume that we should expect manuscript evidence of the DH in existing copies and ancient translations. He ignores entirely the textual evidence for multiple sources, though. One example: Deuteronomy 10 quotes only E’s version of Exodus 34 (when in the text we have of Exod 34 J and E, which were separated independent of Deut 10, are interwoven). We have Psalms quoting one version of the plagues. And, astonishingly, Hamblin neglects the fact that the LXX happens to know only one version of the David & Goliath story in 1 Sam 17, where the traditional Hebrew has both intertwined. This is not specifically DH, but it proves that multiple stories were interwoven from different sources. In a humanities discipline, this is more empirical than one could normally hope for.]

Here he points to two problems: 1) that scholars claim the DH has achieved scholarly consensus in the field and 2) that “An accurately description of the state of scholarly consensus regarding the Documentary Hypotheses, would be more like this: “Those scholars who share a certain set of theoretical and methodological assumptions about the Bible have a consensus that one of several dozen versions of the Documentary Hypothesis is probably correct.””

[So we should not be persuaded by the argument that since scholars agree, it’s true. Fair enough. But, by the same token, we should not be persuaded away from the core because there’s variation at the edges. His analogy about doctors each having a different diagnosis is not apt here. What might be better is of biologists arguing over whether a certain population constitutes a new branch in the species or not. Such argument doesn’t per se destroy the notion of species or even of our general ability to identify differences among them! But again, the bigger problem is that he fails to grasp what the DH is. I will spell it out again. It is the theory that the Pentateuch was composed by the weaving together of 4 core documents. Within this there is indeed variation when it comes to individual verses as well as to steps in the compilation process—i.e., whether there was an earlier stage (a JE redaction, for example) and especially whether there is detectable editorial activity (i.e., did an editor compose his own material to add to the 4 sources?). These are not different documentary hypotheses, these are arguments at the margins. It is true that the trend in biblical scholarship is currently toward non-DH models, and here is another point of misunderstanding. It is not that the Europeans reject the DH in favor of traditional explanations. Rather, they reject the DH and substitute instead an even more bewildering array of hypotheses, which are genuinely different models. But they are all trying to explain the fundamental problems with the text. They do agree that there is at least one source with supplementary material added somehow. But they are not Documentarians. In fact, at the most recent national conference it was joked that the only thing that unites these Europeans is their rejection of the DH! They are now being called non-Documentarians, but again, not because they see any merit in traditional ascription of single authorship. Hamblin seems to have genuinely misunderstood both the DH and the field here.]

Here Hamblin continues to attempt to import scientific methodology to attack the DH, as if we were dealing with materials that can be run through replicable experiments. He says that the methodology is bad because it’s not falsifiable. He points to the invention of the Redactor to explain any piece of text that doesn’t accord with the understanding of the sources.

[While I disagree with the need for the literary analysis represented by the DH to match standards of scientific inquiry geared toward entirely different data, he is right to point to the redactor as a problem. It is one that has been addressed by the Neo-Documentarians, who almost entirely reject the notion of a redactor composing large tracts and inserting them here and there. If we think Kuhn’s work on the progress of scientific knowledge has any merit, we should not be surprised to see a nonlinear progression in something like the DH. Cracks appear and multiply until the theory is either refined or supplanted by something better. We are now seeing it refined dramatically, and it certainly has not been replaced by anything more compelling.]

The point: The DH is unverifiable because “there are no definitive criteria by which it can be decided which particular version of the DH, if any, is correct.” As a side point, he notes that efforts to find sources in Islamic literature and the Iliad were abandoned long ago, so why are they still doing it in Biblical Studies?

[Two things: 1) as Hamblin says, this is the case for all humanities. People make arguments in an attempt to persuade. There is very little proving of anything. 2) As someone so infatuated with standards of proof should know, the fact of the abandonment of efforts to isolate sources in other texts has absolutely nothing to tell us about efforts to isolate sources in the Pentateuch. Why does Hamblin need to go outside Biblical Studies? One could make the same argument from efforts to isolate sources in Joshua, which was once popular but has been largely abandoned! Why do we not just give up on the Pentateuch? For the very simple reason that it responds to problems in this text. Different models were proposed for Joshua because it exhibits fundamentally different features of composition. The methods that generate the DH are only applicable to texts that bear the same features, and if not a single other text in the entire world were composed like the Pentateuch, we should not expect people to continue using methods similar to those that gave us the DH! In other words, other results from other fields have no intrinsic bearing on the DH. The reason that it continues in the study of the Bible is that it successfully explains problems in the text.]

Hamblin’s point: Source criticism is “a massive exercise in circular reasoning” because, I infer, he thinks that source critics assumed that priests talk about priestly stuff, therefore any priestly stuff is the result of a priestly author, which proves that there is a priestly author. He takes issue with the idea that only J knows Yahweh, and only E knows Elohim, that P was the only one interested in genealogies or sacrifice or temple. “You define the P author by his priestly interests, and therefore any passage of interest to priests must have been written by P.”

[This is where it becomes painfully obvious that Hamblin has no idea how source criticism is really done. No one defined a priestly author and then went looking for one. The idea of a priestly author came because when texts were separated there was one that tended to include vast amounts of intimate detail about priestly duties, where the other sources for the most part didn’t. The above quoted sentence is reductio ad absurdum and is unfamiliar with actual practice. He apparently thinks that any talk about priestly stuff means that the dull source critics mindlessly assume it must be coming from an author who is a priest. As a counterpoint, I offer a prime example (that he promptly deleted from his thread when I raised it there): If it’s so circular, why do documentarians universally see Noah’s sacrifice after the flood not as P, but rather as J? Answer: because their arguments are not circular. The way source criticism is done is by making arguments for why the texts present the problems the way they do. Any assertions about the characteristics and interests of an author are made after sources have been isolated. In the past some scholars (after Wellhausen) indeed let these characteristics drive the analysis with bad results. Those are being corrected, and anyone paying attention to current DH debates will have heard documentarians (scholars who see 4 sources) say things like “of course J, as a native Hebrew speaker, knew the word Elohim, and occasionally used it in his writing” on the way to showing how previous generations have gotten off-track by assuming too much. But this does not prove that the entire theory is circular. It would be nice to see Hamblin back up his sweeping assertions with quotes from scholars in the act of circularity. Although he did, in the comments to this post, have trouble reading Joel Baden, or at least quoting him in full. Finally, once again, he calls everyone who sees at least one author at work a “documentarian”. Carr, Schmid, and every other non-documentarian would disagree.]

And a PS: In the comments, which I am banned from, Gregory Smith (if that is his real name) says that he should expect a growing consensus after decades of work if a theory is viable. Hamblin then says Greg is exactly right. I would encourage both of them to read the seminal work of Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, which debunks exactly this idea, using case studies which show the appearance of cracks in the dominant theories and the unraveling of consensus to be hallmarks of progress. The lack of consensus in Pentateuchal studies grew from problems with the application of the theory (like the unnecessary proliferation of redactorial activity), to be sure, which are being corrected in ways that make the case even stronger than it was made in the past.

DH 17: What is the Documentary Hypothesis?

In a post that might more helpfully have come first, Hamblin accuses supporters of the DH of using the rhetorical ploy of defining it as vaguely as possible. “For them, any theory that posits multiple authors in the Pentateuch is DH.” [If he had let me comment, he would know that the opposite is the case!!!] He goes on to show his utter confusion at the situation: “Only a theory that posits a single author for the entire Pentateuch is not DH. I hope I have understood them correctly. They also seem to imply that anyone who accepts source criticism as a useful method is a Documentarian.” Continuing, he cites Baden vs. Schmid as evidence that the DH is hard to attack because it’s a moving target with “Documentarians” so far separated from each other.

[Irony of Ironies! It’s the vague understanding that has allowed nearly every shot of his to miss its mark because he’s not aiming at the DH. He has not understood them correctly at all. Baden is a (neo)-documentarian and Schmid is very much not, by his own admission! Schmid was recently labeled, with others, “non-documentarian” because he, like so many of his European colleagues, are vociferously opposed to the Documentary Hypothesis. This misrecognition, I fear, explains some of the odder claims Hamblin has made in this epic series of posts. One had hoped that, given the title, Hamblin would have actually made an attempt to define the DH. Schmid and others do see fractures in the text that are the result of scribal activity and have proposed a bewildering array of theories, none like the other, to explain how it came to be. The Europeans’ lack of consensus makes the DH look like E=MC2.]

In which Hamblin reports a biblical studies joke that this biblical scholar has never heard. [Not sure where to find the punch line or the humor. Egg-laying, indeed, and a ridiculous metaphor.]

Hamblin gives us all a lesson in the distinction between ontology and epistemology and in criteria historians use (epistemology) for determining historical reliability (ontology).

[What this has to do with the DH he plans to tell us in the next post.]

He tells us that texts about Moses don’t prove Moses was real just like the lack thereof wouldn’t prove the opposite.

[Still not sure what this has to do with the DH. The un/reality of Moses has nothing do do with source criticism. Maybe we’re waiting for historicity 3?]

And here we have come to the end, for now. See my summary comments at the beginning for overall reactions. Once again, I invite Bill to comment here, and maybe to do an open forum on a key text. I hope that these comments help Bill and his readers and our readers to come to a clearer understanding of what the DH is and isn’t.