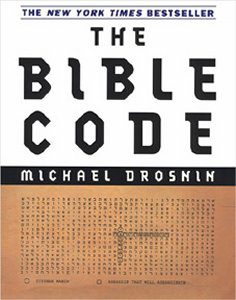

According to Michael Drosnin, author of the bestselling book The Bible Code, there are secret messages lurking in the Torah that only a computer can detect.

According to Michael Drosnin, author of the bestselling book The Bible Code, there are secret messages lurking in the Torah that only a computer can detect.

And thanks largely to his claim to have warned Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin of his impending assassination, Drosnin’s 15 minutes of fame have stretched out to three months and beyond, while his book continues to sit high atop the bestseller list.

But Drosnin has his detractors, and they have begun to speak out. The August 1997 issue of Bible Review featured sharp critiques of Drosnin’s book from two scholars: Ronald Hendel, an expert on the Hebrew Bible who teaches at Southern Methodist University, and Shlomo Sternberg, an Orthodox rabbi who teaches mathematics at Harvard University.

As with many popular books on religion, Drosnin’s stands on the shoulders of more qualified scholars. In his book, Drosnin reprints a paper by Israeli mathematicians Eliyahu Rips and Doron Witztum that originally appeared in the August 1994 issue of Statistical Science.

Rips and Witztum claimed that, if the text of Genesis were treated as one long, uninterrupted string of Hebrew letters, it was possible to find words secretly encoded in the Hebrew text. According to the principle of Equidistant Letter Spacing (ELS), a single word may stretch across verses, even chapters, in the Bible if a consistent number of random Hebrew letters appears between each of the letters in the coded word.

Moreover, Rips and Witztum claimed that pairs of related words such as “hammer” and “anvil” were encoded in close proximity to one another. They also claimed that the names of various rabbis could be found encoded in the text close to the dates of their deaths, even though these rabbis died hundreds of years after Genesis had been written down.

The findings of Rips and Witztum were first popularized in an article by Jeffrey B. Satinover in the October 1995 issue of Bible Review — ironically, the same magazine that is spearheading the current rebuttal.

These early articles prompted Jewish and Christian apologists — including Canadian author Grant Jeffrey, whose book The Signature of God devotes a few chapters to the Bible code — to argue that this research constituted “scientific proof” of the existence of God and the infallibility of the Hebrew Bible.

Although no one has yet tried to find a similar proof for the New Testament, some Christians saw in this research a confirmation of Jesus’ words in Matthew 5:18: “I tell you the truth, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished.”

Drosnin goes beyond the claims of Rips, Witztum, Satinover and Jeffrey. Those authors are careful to note that the Torah forbids divination of any kind; according to them, the Bible code cannot predict the future, but can only confirm events that have already taken place.

Drosnin, however, claims to have predicted Rabin’s assassination. He also claims to have found predictions of, among other things, earthquakes in Los Angeles and nuclear war in Israel.

But Drosnin is not above hedging his bets. Among the dire predictions buried in the text is one message that reads, “Code will save.”

“It is not a promise of divine salvation,” Drosnin writes. “It is not a threat of inevitable doom. It is just information. The message of the Bible code is that we can save ourselves. In the end, what we do determines the outcome. So we are left where we have always been, with one big difference — we now know that we are not alone.”

Some scholars who ignored the earlier claims of Rips and Witztum are taking decisive steps to rebut them, now that Drosnin’s book has ushered them into the popular culture. But not all scholars are following the hype.

Regent College professor Bruce Waltke says the search for coded messages is as old as the Kabbala, a form of Jewish mysticism, and he, for one, does not feel the need to offer a point by point refutation of Drosnin’s claims. “The whole kabbalistic way of doing things is wrong-headed and, I think, demonic,” Waltke says, “and I don’t want to be involved with it.”

Other scholars have pointed out possible flaws in Drosnin’s approach. For one thing, the Bible is not the only text in which computers may find coded prophecies. Sternberg, together with Australian mathematician Brendan McKay, claims to have found the names of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Nicaraguan President Anastasio Somoza encoded in the text of Moby Dick, overlapping such phrases as “the bloody deed” and “he was shot.”

In addition, Hendel claims that Drosnin can’t even get the surface meanings of the text right. In Deuteronomy 4:42, the verse that supposedly predicts Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination, the Hebrew words that Drosnin translates “assassin that will assassinate” should, in fact, read “murderer who murders inadvertently.” And that, says Hendel, is just one of many such mistranslations in Drosnin’s book.

Moreover, Hendel notes that Rips and Witztum performed their original research on the textus receptus, a manuscript which did not become the standard Hebrew Bible until the invention of the printing press in the 16th century. Before that, manuscripts were copied by hand, and even if the words did not change, the spelling — and therefore the number of letters — did.

“Like Shakespearean English, Hebrew spelling was never entirely uniform,” Hendel writes. “These differences in spelling make no difference in the meaning of a word; they are just alternative spellings.”

Martin Abegg Jr., director of the Dead Sea Scrolls Institute at Trinity Western University, echoes Hendel’s concerns, and says he has heard at least one person claim that future editions of the standard Hebrew text should be tailored to make the patterns easier to detect.

“If you start to have to make text-critical choices in order to make these patterns happen, that is troublesome,” says Abegg. “It just shows your bias, and to some degree it becomes circular because then there are things you have to do to the text to maintain the pattern.”

According to Abegg, similar codes have allegedly been found in phone books, and he says it is “foolish” to place too much emphasis on such findings. “We really should expect to see these sorts of things, even in DNA molecules or Moby Dick,” says Abegg. “If you can’t do that, then I suppose you would have to give some credence to what Jeffrey and Drosnin are saying, or look at it seriously. But if you can find these sorts of patterns in other sorts of literature, then I’d say it’s meaningless.”

— A version of this article was first published in BC Christian News.