I don’t know whose idea it was for Valentine’s Day to fall on the first Sunday of Lent this year, but in a way it makes sense. I’m currently reading  Rachel Kadish’s novel Tolstoy Lied; I started reading it because the main character, Tracy Farber, is a professor in a large academic department who is close to her tenure review. Kadish is an academic herself—in my experience only those who have lived in the insanity and pettiness of the academic world are qualified to write about it. Kadish is nailing it. But thirty-something main character Tracy is also in love for the first time, with amusing implications. She thinks too much, is unable to settle into the unfamiliar emotions, and is generally overstressing about everything she and her new love say and do. I recommend that Tracy go on a Lenten retreat. And perhaps do some research on the original Saint Valentine.

Rachel Kadish’s novel Tolstoy Lied; I started reading it because the main character, Tracy Farber, is a professor in a large academic department who is close to her tenure review. Kadish is an academic herself—in my experience only those who have lived in the insanity and pettiness of the academic world are qualified to write about it. Kadish is nailing it. But thirty-something main character Tracy is also in love for the first time, with amusing implications. She thinks too much, is unable to settle into the unfamiliar emotions, and is generally overstressing about everything she and her new love say and do. I recommend that Tracy go on a Lenten retreat. And perhaps do some research on the original Saint Valentine.

So who was this Valentine guy? As is the case with many early Christian martyrs, little is known about him. It’s possible that the stories surrounding Valentine are actually an amalgamation of the experiences of several different persons— “Valentinus” was apparently a popular guy’s name in the third and fourth century Roman Empire. One persistent story is that Valentine ran afoul of an edict from Emperor Claudius II that all Romans must worship the twelve Olympian gods. This isn’t as restrictive as it sounds–I learned a few years ago from a classicist colleague and friend that the Romans were very tolerant of other religions just as long as everyone went through the motions of worshiping the state-approved gods as a statement of community and political solidarity. Eight centuries earlier Socrates got in trouble for apparently failing to obey a similar law in ancient Athens. But as one might expect from a Christian looking to be a martyr, Valentinus would not obey Claudius II’s edict and was thrown in prison. While waiting for his execution, Valentinus’ jailer—noting that the prisoner was a highly educated man—took advantage of the situation and brought his blind daughter to Valentinus’ cell for lessons. Somehow the idea of home schooling in a prison cell seems entirely appropriate.

“Valentinus” was apparently a popular guy’s name in the third and fourth century Roman Empire. One persistent story is that Valentine ran afoul of an edict from Emperor Claudius II that all Romans must worship the twelve Olympian gods. This isn’t as restrictive as it sounds–I learned a few years ago from a classicist colleague and friend that the Romans were very tolerant of other religions just as long as everyone went through the motions of worshiping the state-approved gods as a statement of community and political solidarity. Eight centuries earlier Socrates got in trouble for apparently failing to obey a similar law in ancient Athens. But as one might expect from a Christian looking to be a martyr, Valentinus would not obey Claudius II’s edict and was thrown in prison. While waiting for his execution, Valentinus’ jailer—noting that the prisoner was a highly educated man—took advantage of the situation and brought his blind daughter to Valentinus’ cell for lessons. Somehow the idea of home schooling in a prison cell seems entirely appropriate.

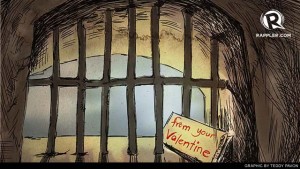

The jailer’s daughter Julia was very bright and learned a great deal in a short time, including that Valentinus believed that the God he worshiped and who was responsible for him being in prison actually answered prayers. “Will God heal my blindness if we ask?” Julia wanted to know, and sure enough when she prayed with Valentinus, there was suddenly a brilliant light in the prison cell and for the first time in her life, Julia could see.  The evening before his execution, Valentinus sent a note to Julia urging her to stay close to God—he signed it “From your Valentine.” And the rest is history. In addition to being the patron saint of engaged couples and happy marriages, according to the History Channel website Saint Valentine is also in charge of beekeeping, epilepsy, fainting, the plague and travelling. Lots of multitasking going on in saintland, apparently. But I can see that—other than the beekeeping, all of those other things fit with love relationships.

The evening before his execution, Valentinus sent a note to Julia urging her to stay close to God—he signed it “From your Valentine.” And the rest is history. In addition to being the patron saint of engaged couples and happy marriages, according to the History Channel website Saint Valentine is also in charge of beekeeping, epilepsy, fainting, the plague and travelling. Lots of multitasking going on in saintland, apparently. But I can see that—other than the beekeeping, all of those other things fit with love relationships.

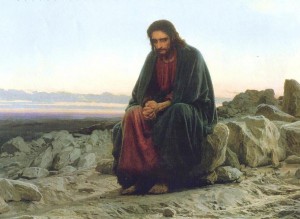

At first look, yesterday’s scripture readings are far more appropriate for the first Sunday of Lent than for what Valentine’s Day has become in our contemporary world. But maybe not. T he gospel reading from Luke, for instance, describes the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness. Moral of the story—the temptations of material things, power, and fame are always seductive and present, seeking to distract each of us from where our focus should lie. Stripped of everything, including his freedom and eventually his life, but also stripped of everything that might distract him from his central focus and belief, Valentine became a channel of transcendent goodness and power. Yesterday’s Psalm 91, one of my favorites, reminds us that our strength is to be found in divine shelter, shadow, and quietness rather than in the more obvious sources of manic energy and stress. Paul reminds us in yesterday’s passage from Romans that “the word is near you, on your lips and in your heart.” The energy of Lent, as well as of yesterday’s readings and the Valentinus story, is all about renewed commitment and inward exploration—none of which guarantee outward success, but without which full humanness is impossible.

he gospel reading from Luke, for instance, describes the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness. Moral of the story—the temptations of material things, power, and fame are always seductive and present, seeking to distract each of us from where our focus should lie. Stripped of everything, including his freedom and eventually his life, but also stripped of everything that might distract him from his central focus and belief, Valentine became a channel of transcendent goodness and power. Yesterday’s Psalm 91, one of my favorites, reminds us that our strength is to be found in divine shelter, shadow, and quietness rather than in the more obvious sources of manic energy and stress. Paul reminds us in yesterday’s passage from Romans that “the word is near you, on your lips and in your heart.” The energy of Lent, as well as of yesterday’s readings and the Valentinus story, is all about renewed commitment and inward exploration—none of which guarantee outward success, but without which full humanness is impossible.

Each of the past three Ash Wednesdays I have posted an essay on this blog about why I think that Lent is a bad idea. For those who observe Lent, practices are often trivialized and simplified so that anyone can do it and feel good about themselves, just as Valentine’s Day in the twenty-first century makes a mockery of its ancient roots.

But this year I’m remembering the first time I ever did anything for Lent. Over twenty-five years ago I attended an Episcopal men’s silent retreat during Lent, an experience that I look back on now as being the first of an unexpected series of events over the years that incrementally awakened and changed me internally.  I first read Simone Weil at that retreat; studying, teaching, and writing about her thought has shaped me in more ways than I can count. I gained insights into why teaching is my vocation at that retreat. I first poked my toe into the waters of silence as spiritual practice at that retreat. Most importantly, at that retreat I for the first time began to suspect that God could be a reality in my life at a deeper level than intellectual assent. It has taken many years for this to develop—I’ve noted before that my encounters with the divine are more like a gentle drizzle than a steady rain—but I’m not the same as I was. Thanks, Lent.

I first read Simone Weil at that retreat; studying, teaching, and writing about her thought has shaped me in more ways than I can count. I gained insights into why teaching is my vocation at that retreat. I first poked my toe into the waters of silence as spiritual practice at that retreat. Most importantly, at that retreat I for the first time began to suspect that God could be a reality in my life at a deeper level than intellectual assent. It has taken many years for this to develop—I’ve noted before that my encounters with the divine are more like a gentle drizzle than a steady rain—but I’m not the same as I was. Thanks, Lent.

One need not be Christian, or religious at all, to experience the healing value of what Lent offers. Finding a space of silence, quietness, attentiveness, and deliberation in the middle of a world that values none of the above is a challenge—but one worth taking up. This is why I recommend that Tracy go on a Lenten retreat. It beats finding all the above in a prison cell.