A typical plot complication on reality shows involves the unexpected twist, a challenge that the credulous competitors never saw coming: The next leg of the race will occur underwater, in an eel-ridden cove, says the host; the next round of the bake-off will require the incorporation of mountain oysters in a rendition of Crepes Suzette. The idea is simple: the greater the skill, the greater the capacity to overcome.

A typical plot complication on reality shows involves the unexpected twist, a challenge that the credulous competitors never saw coming: The next leg of the race will occur underwater, in an eel-ridden cove, says the host; the next round of the bake-off will require the incorporation of mountain oysters in a rendition of Crepes Suzette. The idea is simple: the greater the skill, the greater the capacity to overcome.

If there were a reality show writing competition (imagine that), the curve might come by way of a forced employment of cloying conceits: “Write a profound story using a waterfall, a widowed grandfather, a daisy—aaaaaannnnnd a basset hound puppy. You have thirty minutes. Break my heart.”

Then the topper would require that it be set around Christmastime. For if anything can lose flavor faster than cheap Christmas candy, it’s a maudlin Christmas story.

Unless you’re a master, that is.

Because if you’re a master, not only can you set the tale at Christmas, but you can also revolve it around a young boy’s death, and for extra measure include—wait now—wait for it: a moth emerging from a cocoon.

I never tire of telling people about Nabokov’s short story, entitled—audaciously—Christmas. Few have read it. Most are put off by the name. But once they’ve looked it up, they always remember.

The short narrative involves a Russian estate holder returning home to entomb the body of his recently deceased son.

As the story opens, Sleptsov (“blindness” in Russian), is sitting in a corner of his great manor’s annex, a cozy branch attached to the main structure, now closed tight for the winter. He cannot remember having been there before, and finds it comforting, akin to the kind of unlooked for solace that might be offered by a perfect stranger, whose words can somehow ease a mortal pain even better than those of a brother.

But there is much in store for Sleptsov on this cold Christmas Eve night, one in which he claws at the corners of his sorrow. For grief is like that unvisited annex of the house; when it comes, it is always a condition in which you have never been before, a place that you never meant to go. It traps you, leaves you swallowing and blinking wildly at a reality that presses close with a poker’s heat.

Still, that is the very place, of all places, where the inversion occurred—where what Eliot calls “the birth that seemed like a death” took place, and where the death, that is in fact a birth, took place.

Sleptsov moves through the dazzling brightness of a snow-filled world, amazed to be alive after what has transpired. How can he still see and hear? How can he breathe? The worst has happened—worse than his own death or any fear of it: the death of his child; but the world carries on regardless, and he in it.

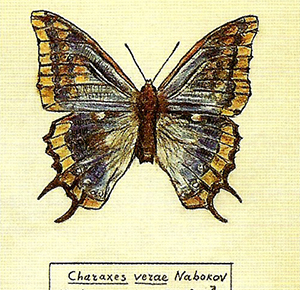

Alone, with only a kindly servant, Sleptsov has the great house opened. He walks through its somber halls, the furnishings wrapped with the drapes of the summer’s closing. The sepulchral shadows are barely disturbed by the flicker of his candle, and memories of the boy he has lost rise about him in pale flames. From his son’s study, he takes the butterfly net that still smells of summer, a notebook in which he had catalogued his conquests, and a chrysalis inside a tin box, one of his last purchases.

Back in the annex, the servant has placed a small green Christmas tree on the table. But the very sight of it hurts Sleptsov; he wants it taken away so that he can be alone with his sorrow. Then, turning through the pages of the notebook, he finds something that pushes his heart to its limits. His boy wrote not just of the butterflies that he loved to capture, but also of a secret love that he had for a girl—something Sleptsov had no idea about, and now will never know.

The grief of learning too late is one thing, but learning that there were aspects of the beloved he had no inkling of—that there was a universe of depths unplumbed? These things can bring the heart to bursting. For is grief not the pain of having nowhere for the love to go? There it swells, stifles, and chokes in the throat, dammed forever.

“I—can’t—bear—it any longer,” Sleptsov cries.

And with the unendurable pain comes the curious conviction that he will die this very night. Yes. Death. How simple it will soon be. He closes his eyes, and a miracle-bereft life stretches emptily before him.

Then—at the breach of agony—it happens.

It happens “because a man overcome with grief had transferred a tin box to his warm room, and the warmth had penetrated its taut leaf-and-silk envelope; it had awaited this moment so long, had collected its strength so tensely, and now, having broken out, it was slowly and miraculously expanding” to the point that it takes “a full breath under the impulse of tender, ravishing, almost human happiness.”

And isn’t that Christmas? Isn’t that love? Isn’t that testament to what is greater than nature? It would burst the grave’s ground, wouldn’t it? Wouldn’t it explode the barren chasms of space and shame the quasars with its radiance?

Because there is nothing vaster than this. The synonym for vastness is love, a power exclusive to the human soul.

In death, we grieve, like fresh cracks in dry skin, like picked scabs, blossoming with blood’s roses. But in grieving, we love, and thereby love lives—sore and longing—yet vital and unendable and rich, so rich, of promise. For in this rock-ribbed, hoary night, it spreads its cry like sun-warmed wings, like the sons of David, born of dawn.