Blessed Santa Barbara, / Your story is written in the sky, / With paper and holy water.

Blessed Santa Barbara, / Your story is written in the sky, / With paper and holy water.

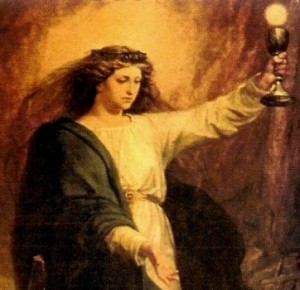

December 4 marked the feast day of St. Barbara. An early martyr, St. Barbara announced her faith to her pagan father by having three windows—a sign of the Trinity—cut into a wall of her private bath. It is said that the torches St. Barbara’s father used to torture her would extinguish themselves before they could be pressed against her skin.

My mother, also named Barbara, spent her summers cleaning the rooms of my grandfather’s motel; memories of the task still make her shudder. My grandfather refused to wash sheets or towels, and was either too drunk or angry for my mother to ask for a clean washrag.

“I cannot stand dirt,” she says, filling her sink with soapy water, reaching for the spoon I used to spoon sugar into her coffee. Her cigarette rests on the sink’s aluminum edge, its ash hovering over the sudsy water, which she will use to wash the spoon and the rest of the day’s dishes. It is a better spot for the cigarette than the counter by the stove, which, she has mentioned, is now miraculously free of grease stains.

“Baby oil! A little bit just rubs the grease away,” she exclaims, somehow forgetting how flammable baby oil is, how easily it could set her small kitchen ablaze, the file cabinet holding her life’s paperwork sidled next to the stove, the first thing to go should the oil spark.

If I were to hold my mother up to her unofficial patron, I would see two women whose lives were vastly different, one a patron of those who work with explosives, the other always on the verge of exploding—the dishes clanging together in her hands, her jaw set against whatever she believed was working against her: my father’s obstinate silence, the weight of our poverty, the childhood memories that she drank to avoid.

But the memories and her marriage to my father were too large a strain for her to hold anything together, and believing that she didn’t belong to my father or to us, she took a lover, left my father, and plummeted my siblings and me into years of abuse and neglect, her lover’s words turned sour by his fists and wandering hands, her ability to care for us compromised by her desire to be loved and known in the way she saw fit.

Iconographers believe that they are “writing,” or translating, the saint’s life into a story that, through the power of image, draws us into that life. The intention is holiness: the icon is a window into the particular movements of a holy person’s spiritual journey, and by approaching the icon with reverence, your own journey becomes more visible, more easily known and understood.

But the more I approach my mother’s life, the less I understand. During the long night stretches of nursing my son, I brood over what I remember, worrying that the same anger rising in me is what rose in my mother, that it will someday uproot me the way it continues to uproot her, our phone calls filled with her complaints about gangbanger neighbors, the length of time it has taken for me to return her last phone call.

What holds true about the writing of icons is what holds true for us: the icon is a glimpse into the fullness of the kingdom of God, and what we behold in paint and wood is what we must behold in each other. If St. Barbara is holy, it is Christ dwelling in the particulars of her life that makes her holy; it is Christ who watches us as we kiss and kneel and pray.

Do I doubt that God dwells in the particulars of my mother’s life? Do I look for vindication that she is a terrible person, or at least, that she has been a terrible mother, my own heart still racing in fear every time I hear her voice on the other line? Is it impossible, now, for me to see God in her?

It has occurred to me that, in writing about my family life, I am trying to write our icon, and that it will possibly remain unfinished in my sight, that what I perceive as impassable anger will, at the end, be transformed into something I can only long for, blind and unbelieving as I am.

In traditional iconography, it is common to depict the saint with defining artifacts from her life. St. Barbara is often shown holding a small tower, a representation of the actual tower in which her father locked her during her girlhood.

What are the artifacts of my mother’s life? Cigarettes, Heineken bottles, suicide notes my siblings found tucked beneath piles of mail?

Or would an icon of my mother show her holding flower seeds, blooms sprouting out of the paper seed packets, her hands stretched out and open?

For while it is true that my mother hates dirt, she also loves it, loves to save whatever flowers are wilting in the grocery store garden section and plant them in her yard. She waters whatever grows: morning glories, pansies, sunflowers with monstrous heads.

“Look at these guys!” she exclaims, waving a hand toward the kitchen window, the sunflowers peeking in. “They just spring right out of the ground! I love them!”

I could be jealous of the flowers, envious of how they elicit so much care from my mother. But what can I say? She presses a large paper bag of wildflower seeds into my hands; the seeds are old, but “plant them anyway,” she says, “just see what blooms.”

I keep the seeds with me for years, and finally plant them on a whim, digging two long furrows up the walkway to my front door.

And my yard explodes with blossoms of blue and white, flowers I cannot name but which remain standing after the first snowfall, their faces turned toward my windows, watching.