Presence to others: The sense of our presence to each other increased on the day the students in my freshman honors colloquium on the Sabbath observed a secular mini-Sabbath. That day, designed by the whole class, included a number of Sabbath appropriate activities: no technology; natural and candle-light instead of fluorescent lighting; festive attire; food (bagels and cream cheese, of course!); song; private meditation; expressions of gratitude; and communal text study.

Presence to others: The sense of our presence to each other increased on the day the students in my freshman honors colloquium on the Sabbath observed a secular mini-Sabbath. That day, designed by the whole class, included a number of Sabbath appropriate activities: no technology; natural and candle-light instead of fluorescent lighting; festive attire; food (bagels and cream cheese, of course!); song; private meditation; expressions of gratitude; and communal text study.

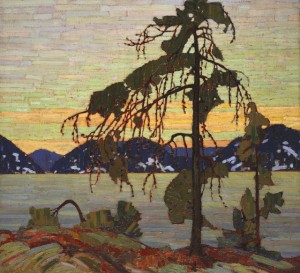

The text? This, by Wendell Berry, from A Timbered Choir: The Sabbath Poems 1979 – 1997:

I go among trees and sit still.

All my stirring becomes quiet

around me like circles on water.

My tasks lie in their places

where I left them, asleep like cattle.

Then what is afraid of me comes

and lives a while in my sight.

What it fears in me leaves me,

and the fear of me leaves it.

It sings, and I hear its song.

Then what I am afraid of comes.

I live for a while in its sight.

What I fear in it leaves it,

and the fear of it leaves me.

It sings, and I hear its song.

After days of labor,

mute in my consternations,

I hear my song at last,

and I sing it. As we sing,

the day turns, the trees move.

After I read the poem aloud, I opened the circle to observations. Silence, then a comment. Maybe there was another comment, and then more silence.

By this point in the semester (just after fall break), silence had become a regular part of our class. This particular morning, however, the silences were, for me, unsettling. But I let them be. Silence, too, time for reflection, if that’s what was happening, is part of a Sabbath experience.

The students who did speak responded to the passages in the poem about fear. They offered generalizations about how people experience fear, how people overcome fear. The comments were nice, but generalizations are easy to make and often lack authority. I wanted the class to get personal.

So, I asked. What do you fear?

I am afraid of discovering one day, too late, that I’ve led a life without meaning, said one student.

Even though I know it’s irrational, I’m afraid of the dark, said another, who, for his festive clothing, wore his Eagle Scout uniform to class.

I have an irrational fear of heights, said a third student. Just standing at a drop of ten feet makes me uncomfortable, and I have no choice but to back away. Sometimes I have dreams in which I have to crawl through terrifying architectural mazes of narrow, rail-less pathways hundreds of feet above the ground. It is an uncontrollable terror that makes no sense.

The last student to speak told of a horrible car accident that nearly took her sister’s life, and of heading to the hospital not knowing her sister’s condition, and of her fear of seeing her sister for the first time not long after she had been admitted to the hospital.

Davis, the student with the fear of heights, who was skeptical about our in-class mini-Sabbath experience, and who regarded the preparations for it to be mostly a “hassle,” wrote this about the day:

Once our reflections on the [poem] began to turn into personal experiences and emotions, I felt an open connection with the group I had not felt before. Even though not everybody…contributed, we all still had to listen to what others were saying, and that can be just as engaging as actually speaking what you feel. One of the purposes of the Sabbath is to build a stronger community. I believe our class Sabbath accomplished that by allowing us a more relaxed and free environment in which to share our thoughts. Fears we consider silly or excessive or personal can be difficult to share, and yet we managed a personal discussion where all these were mentioned for all to listen to—and perhaps, as we worry, judge, though I doubt that happened in our community.

“I still like the idea,” writes Judith Shulevitz in The Sabbath World, “of the fully observed Sabbath more than I like observing it.” Maybe Davis feels the same way.

The Sabbath is a “hassle.” For one thing, it’s a big inconvenience. In Jewish tradition, the Sabbath arrives and departs at fixed times. Not entirely unlike the sounding of a bell that interrupts, for the third time in a class period, a lively discussion and that prompts one student to say, exasperated, come on, do we really have to? No, alright, we can skip it this time, I give in. Maybe they don’t see the value in this kavanah exercise. Maybe they don’t like it. Maybe I didn’t think it through and introduce it effectively. Maybe…

It’s hard to submit to laws that seem arbitrary. Even I, author of this particular “law,” cannot abide by it. Don’t ask how I “keep” and “remember” the actual Jewish Sabbath.

Yet, I think, I hope that the students in my freshmen honors class have experienced the value of stopping, stopping in time, even when, as good honors students—having arrived on campus with an already exhausting resume of accomplishments—they feel driven to perform, produce, excel. I think, I hope they have experienced the value of learning within a community, which means, in part, learning to listen deeply not just to texts, but to each other.

Listening deeply to others, human and non-human, whether physically present or present digitally or in print, and resting from labor: these are two ways of achieving “inner liberty,” liberty from, as Abraham Joshua Heschel writes in his profound, lyrical meditation, The Sabbath,“ the will to be a slave to one’s own pettiness.” The essence of a Sabbath practice, says Heschel, is to create conditions in which one might experience, again and again and again, a taste of inner liberty.

Inner liberty: isn’t that what a liberal arts education hopes to provide students and professors alike? A liberal arts education, a Sabbath practice: their name is One.

Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this essay.

Richard Chess is the author of three books of poetry, Tekiah, Chair in the Desert, and Third Temple. Poems of his have appeared in Telling and Remembering: A Century of American Jewish Poetry, Bearing the Mystery: Twenty Years of IMAGE, and Best Spiritual Writing 2005. He is the Roy Carroll Professor of Honors Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. He is also the director of UNC Asheville’s Center for Jewish Studies.