Job confounds. A book in which God allows “the satan” to overwhelm a righteous man, purely to prove that Job’s righteousness and fear of God come not from God’s blessings, but instead are rooted in a respect for the creator. The premise thus seems simple enough: love God at all times; let not material and spiritual health and prosperity dictate whether or not you worship the Lord your god. After his servants are murdered, his livestock stolen, that is, his livelihood carried away and slaughtered:

Then Job arose and tore his cloak and cut off his hair. He fell to the ground and worshiped.

He said,

Naked I came forth from my mother’s womb,

and naked shall I go back there.

The LORD gave and the LORD has taken away;

blessed be the name of the LORD!”

In all this Job did not sin, nor did he charge God with wrong.

(1:20-22)

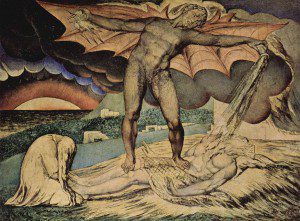

God allow “the satan” to further curse Job. This time with boils. And it is here that the story becomes interesting. It is not just that Job refuses to curse the name of the Lord; it is not just that he endures patiently. Rather, he refuses consolation. His wife scolds him; his friends attempt to make sense of the disaster, and Job, against all of what we might call common sense, refuses to budge:

He took a potsherd to scrape himself, as he sat among the ashes. Then his wife said to him, “Are you still holding to your innocence? Curse God and die!” But he said to her, “You speak as foolish women do. We accept good things from God; should we not accept evil?” Through all this, Job did not sin in what he said.

Now when three of Job’s friends heard of all the misfortune that had come upon him, they set out each one from his own place: Eliphaz from Teman, Bildad from Shuh, and Zophar from Naamath. They met and journeyed together to give him sympathy and comfort. But when, at a distance, they lifted up their eyes and did not recognize him, they began to weep aloud; they tore their cloaks and threw dust into the air over their heads. Then they sat down upon the ground with him seven days and seven nights, but none of them spoke a word to him; for they saw how great was his suffering. (2:8:13)

For many, many chapters the books drags on. Job’s friends oscillate between offering consolation and offering diagnoses. He must have done something wrong to deserve such horrors; he cannot be blameless, for who is blameless? Job, however, refuses to budge. He is, if afflicted, honest. For a time, he sounds not unlike Qoheleth of Ecclesiastes, devoted to how meaningless all seems in the face of overwhelming suffering. God himself eventually thunders forth from the sky; He scolds Job. How dare a mere man castigate the creator! How dare one with knowledge of so little pretend that his paltry existence can comprehend truth!

At first, Job complains; he talks back, so to speak. But, by the end, all is restored to him, though only after he confesses:

I know that you can do all things,

and that no purpose of yours can be hindered.

“Who is this who obscures counsel with ignorance?”

I have spoken but did not understand;

things too marvelous for me, which I did not know.

“Listen, and I will speak;

I will question you, and you tell me the answers.”

By hearsay I had heard of you,

but now my eye has seen you.

Therefore I disown what I have said,

and repent in dust and ashes.

(42:2-6)

This passage seems straightforward enough: repent and love. No human being can know all things, can expect anything, such is pride, a projection of mere humanity onto the Lord of Heaven, the God who will eventually become man. All of this is, of course, true enough, but it is best read against the Lord’s final speech to Job:

Adorn yourself with grandeur and majesty,

and clothe yourself with glory and splendor.

Let loose the fury of your wrath;

look at everyone who is proud and bring them down.

Look at everyone who is proud, and humble them.

Tear down the wicked in their place,

bury them in the dust together;

in the hidden world imprison them.

Then will I too praise you,

for your own right hand can save you.

Look at Behemoth, whom I made along with you,

who feeds on grass like an ox.

See the strength in his loins,

the power in the sinews of his belly.

He carries his tail like a cedar;

the sinews of his thighs are like cables.

His bones are like tubes of bronze;

his limbs are like iron rods.

[…]

Can you lead Leviathan about with a hook,

or tie down his tongue with a rope?

Can you put a ring into his nose,

or pierce through his cheek with a gaff?

Will he then plead with you, time after time,

or address you with tender words?

Will he make a covenant with you

that you may have him as a slave forever?

Can you play with him, as with a bird?

Can you tie him up for your little girls?

Will the traders bargain for him?

Will the merchants divide him up?

Can you fill his hide with barbs,

or his head with fish spears?

Once you but lay a hand upon him,

no need to recall any other conflict!

Whoever might vainly hope to do so

need only see him to be overthrown.

No one is fierce enough to arouse him;

who then dares stand before me?

Whoever has assailed me, I will pay back—

Everything under the heavens is mine.

I need hardly mention his limbs,

his strength, and the fitness of his equipment.

Who can strip off his outer garment,

or penetrate his double armor?

Who can force open the doors of his face,

close to his terrible teeth?

(40:10-18, 25-32; 41:1-6)

On the one hand, this reads like divine gobbledygook: I made the world full of things you can’t control. That’s that; shut up. But to my eyes, and in my own experience, this misses the point. What God tells Job to forsake is control, is the belief not only that he is the center of the universe, but more concretely that he, as a single human being in a wide world filled with horrors—worst of all other human beings—can exert his will over others.

Is this not the case? Is this not what it means to be human? If a loved one makes a bad decision, I may try to stop him or her, but I cannot ultimately make the decision for them. If I beg a friend to forgive me, I may do all in my power, but what can I really do to soften his hardened heart? Live with my guilt? Pray for compassion?

Yes, that is it: prayer. Job, in my eyes, is a lesson in prayer, fundamentally a critique not merely of pride, but of power itself. The world is as it is, filled with suffering. We try to do what is right; we make mistakes, and cannot guarantee any outcome. Every breeze, every harsh rain, every other human being—these are completely out of our control as individuals, radical, though mundane, reminders of our utter powerlessness in the face of an existence filled with others who feel themselves as in control as we do (that is, they feel themselves powerful, yet constrained by the same fact of total powerlessness).

What is left but to pray? What is left but to keep silent before the majesty of being? All we can do is let go. Fight as we must (as we cannot help but do as human beings), but always with the knowledge that control is not ours—power is not ours. Job is the truth of Christ’s words about the lilies of the field; Job is our ultimate consolation in the form of consolation’s own death.