It’s no secret that I love Dorothy Day. She has helped me make sense of a Church that can often seem riven by division, academic equivocation, and a strangely-conservative politics. I don’t see much negative about Day, but she’s long been subject to criticism: she was a liberal (never mind her Anarchism and avowed anti-capitalism), she hated the sexual ethic of the Church, she opposed what it means to be an American.

Her Byzantine analogue (and who knew she had one?), Fr. David Kirk, has largely been spared such attacks. Perhaps it’s because there are fewer Byzantines; perhaps it’s because he wrote less (though one has to admire the snap of a title like Quotations from Chairman Jesus). In writing this piece to carry his legacy to more people, I might run the risk of opening him up to attack. I hope not, but his life and legacy seem so beautiful to me that it’s incumbent upon me to use my meager soapbox to say a meager something.

So who was he? One could say a priest, an activist, even a saint. It might be best, therefore, to start with a short biography.

Fr. Kirk was born in Louisville, Mississippi in 1935 to Baptist parents. The racial tensions of the South of his youth would come to shape him. At the age of 12, he supposedly befriended a black man named Clint who was accused of murdering his wife. Young Fr. Kirk brought him food in the woods where he was hiding until Clint (whom I presume he thought was innocent) could escape to Louisiana.

This might seem a strange story with which to lead, but it begins to illustrate a major theme in Fr. Kirk’s life, one could even say the thing that brought him to the Melkite Church and drove his lifelong work for the poor: radical community and hospitality (especially with regard to race). An anecdote to this point:

According to Dr. Albert J. Raboteau, a member of the Emmaus House Board, Father David had a life-long interest in interracial justice. As editor of his high school newspaper in Mobile, AL, he spent several weeks attending the local black high school to investigate first hand the inequities of segregation. In 1956, his junior year at the University of Alabama, Arthurine Lucy’s attempt to integrate the school was met with mob violence. He joined with several other students to shield her as she moved about campus. His correspondence with William Faulkner during that same year elicited a letter—later published—detailing the famous author’s views on segregation. (OCA.org)

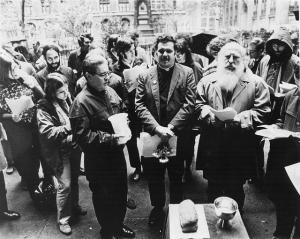

To continue with his biography: he became a Melkite Catholic (one of the twenty-three Eastern Catholic Churches) in 1963 and was ordained to the priesthood. Fr. Kirk became active in the Civil Rights Movement (even getting arrested with Martin Luther King Jr. once). He moved to New York City to work with Dorothy Day, who told him he was more needed in Harlem. Thus he went there and Emmaus House was born. Over time 60 Emmaus Inns were founded—apartments scattered across the City, intended to help women escape abusive, crack-infested environments.

What is Emmaus House?

The work of Emmaus has involved a traveling kitchen to feed the homeless; job training; Emmaus Inns (apartments for the homeless); legal services for the homeless; and a residence for the homeless.

All of those who live at Emmaus must get the counseling they need, take some responsibility for their education, and do work to help sustain the community. (Incommunion.org)

It is much like a Catholic Worker House (on which it was modelled): it provides for the homeless in a multitude of ways, making available food, medical care, legal assistance, housing, and more. It takes seriously the corporeal and spiritual works of mercy, bringing them together by offering a place for material consolation and a spirit of hope. As one resident put it:

My name is Winifred Daniels. I used to smoke crack and I used to drink. Father David used to call it, the community of wounded. We all are wounded in one way or another and we’re here to help one another. (NPR.org)