This week’s lectionary is a little bit different. This week, in contrast to most other weeks, there is the option to go in two pretty different directions. You can choose to observe Palm Sunday, which is a fairly triumphant day full of procession, Hosannas, and glory—even if it ends in solemn anticipation of Jesus’ suffering that is to come. Alternatively, you can choose to observe Passion Sunday, which moves the story of Jesus’ death right up to the present. Here, you’re recounting Jesus’ trials and sufferings on a Sunday, a bit ahead of schedule for holy week. The lectionary provides for both, so we will look at both options below. We’ll start with the text for Passion Sunday, and then consider the Palm Sunday texts at the bottom.

Isaiah 50:4-9

What It’s About: This is one of those prophetic passages that deals with persecution: how does someone who is being set upon by his (or her) enemies cope with the events? The Christian tradition has often taken these texts as prefiguring the suffering of Jesus on the cross, which is why this one shows up in the lectionary for Passion Sunday.

What It’s Really About: It’s really about that person’s enemies at that place and time, but that hasn’t stopped Christians from reading them as relating to Jesus. And that’s legitimate—but we shouldn’t forget that these texts come from a specific circumstance that wasn’t Jesus’ suffering.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about whatever Mel Gibson thinks it’s about. Mel Gibson and others who make films about Jesus often look to these texts from the Hebrew Bible to fill in details about Jesus’ passion. So films will sometimes have people pull out parts of Jesus’ beard, since it’s presumed that these verses are previewing the actual events of Jesus’ life. But that’s not really a fair reading of this text, on its own merits.

Maybe You Should Think About: How does the identity of the “me” in verse 4 relate to the rest of the text? Is there something about the task of teaching that makes the rest of all this inevitable? Or predictable? It’s an odd detail, the teacher thing. What’s up with that?

Psalm 31:9-16

What It’s About: Very much the same thing that was going on in the Isaiah text! Here, someone is surrounded by his (or her!) enemies, and is crying out to God for help.

What It’s Really About: Someone who offends sensibilities. Look at verse 11: horror to the neighbors, dread to acquaintances. Think about who fits that description, and the description of someone people flee from when they see them in the street. That’s who this is about.

What It’s Not About: It’s still not really about Jesus’ suffering. Well—it is and it isn’t. It is about Jesus’ suffering, in that this psalm is a stand-in for all the suffering that persons undergo at the hands of others. But it’s not about Jesus’ suffering, in any historical sense. But that’s good news: it can apply to anyone! And Jesus’ suffering can be a sign to us, in the same way that the suffering of this psalmist was a sign to early Christians.

Maybe You Should Think About: Verse 12 has a couple of interesting lines. “I have passed out of mind like one who is dead,” and “I have become like a broken vessel.” I guarantee that there are people in every community who have felt that way, or who currently feel that way. In Lent, and especially on this Palm or Passion Sunday, the focus will be on Jesus’ suffering. But Jesus is not the only one who has ever suffered. What can this psalm say about the everyday suffering, isolation, and pain of normal people?

Philippians 2:5-11

What It’s About: This is one of the most concise, poetic expressions of Christology in the New Testament.

What It’s Really About: This is from one of Paul’s letters, but most scholars don’t think Paul actually wrote it. Rather, most people think that here Paul is quoting something or someone. This is often called the “Christ hymn,” because this was a bit of material—perhaps a hymn or poem or proto-credal statement of some kind—that Paul embedded in his letter. By doing this, Paul would have been able to communicate something to the audience of his letter that he wouldn’t have been otherwise able to do: he would have signaled to them a kind of common tradition and common belief and understanding. In the so-called “Christ hymn,” we may have one of the earliest statements about Jesus that survives from the ancient world.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about the Apostles’ Creed or the Nicene Creed, and it’s certainly not about the Westminster Confession or some other modern statement of faith. It’s important to understand that every creed or statement of faith (if that’s what this even is) belongs to its place and time. Here we have something remarkable, but it’s not quite exactly what Christian theology later came to espouse. It’s good to be ok with that; Christianity did not spring fully-formed from the head of Jesus.

Maybe You Should Think About: If you choose to preach on this, maybe you should consider how this bit of early Christian kerygma meshes with your own tradition’s statements of belief. How much water has gone under the bridge in the intervening millennia? What do you believe now that Paul would have omitted, rejected, or been confused by?

Mark 14:1-15:47 (or 15:1-39)

What It’s About: This is the passion narrative. This is the earliest version of it we know, from the earliest evangelist, Mark. And here the passion is immediate and rushed—almost sweaty and desperate in its pacing and imagery. If you are doing Passion Sunday, this is what you are reading.

What It’s Really About: One of the nice things about the lectionary is that it invites us to read the gospel accounts on their own merits, without conflating them with each other. This is especially valuable in the case of Mark, since Mark so often gets steamrolled by its daughter texts Matthew and Luke. But here, there is a chance to hear Mark’s passion story on its own terms, unadorned by later readers and redactors. And Mark’s story is stark. It is panicky, in places, and in it the story of Jesus’ death is nowhere near as certain as later Christian theology made it out to be. This is the story before many of the nice theological bows had been tied onto it, and it can be jarring to take it on its own terms.

What It’s Not About: This is not about a smooth story that is tailor-made for Christian theology and liturgy. Mark’s account almost has the quality of a draft, or better yet, of an account jotted down on a bar napkin before it could be forgotten. Mark makes very few attempts to smooth things over. That’s not to say the text isn’t artful. Look at the way Mark begins this section with the woman with the alabaster jar. If you were reading (or more probably, hearing it) this text for the first time, that story might not strike you as important. But as the narrative progresses through chapters 14 and 15, the woman’s actions would take on more and more gravity, until the full weight of her anointing had become clear. Likewise with Judas. Ironically the disciples in Mark don’t get much credit, being portrayed as bumbling idiots. But Judas here has agency and purpose that stands out, and that gives the first-time reader a sense of doom that we might be able to appreciate on our tenth or hundredth or thousandth reading (or hearing).

Maybe You Should Think About: Raphael’s School of Athens is one of my favorite pieces of art, for a lot of reasons. It is an ode to reason and classical culture, yet it is painted on the walls of the papal apartments. It’s a who’s who of western learning, and yet the scene it depicts is pure fantasy, corresponding to no period of history and no gathering that could have ever existed. But one of my favorite parts of it is the young man at the lower right, just to the left of the column, looking directly at the viewer. Many people think that this is Raphael’s “signature,” his way of leaving his mark on the painting.

Think about that, and then consider Mark 14:51. What’s going on with that guy? Why is he mentioned, in such precise, embarrassing detail? One of my favorite unprovable theories about the bible is that this is the author of Mark, inserting himself into the story in the only way he fit. Perhaps “Mark” (all the gospels are anonymous, but we’ll call him Mark out of convention) was a young man during Jesus’ ministry, a hanger-on to Jesus and the disciples. And maybe he was loitering nearby during the events in these chapters, and he played the small part mentioned here, and he inserted it into the story. I don’t know if that’s true, but I hope it is. And if it is true, here’s something to think about: what is our angle on this story? Where do we fit in, even if it’s only in the corner, looking knowingly at the viewer. Where is our place?

Bonus Palm Sunday Texts:

Psalm 118:1-2, 19-29

What It’s About: This is the pomp! This is the circumstance! This is your triumphal entry!

What It’s Really About: This is one of many psalms describing ceremonies, processions, and festivals about which we no longer know very much. Sometimes we can discern that one has something to do with the coronation of a king, or was connected to a certain holy day. But mostly these contexts are lost. In the case of this one, two things make it compelling reading for Palm Sunday: that it describes a procession, and that it seems to be about someone very important—a cornerstone, as the text puts it, for the whole enterprise!

What It’s Not About: It wasn’t written for the occasion of Palm Sunday, and that is important to remember. Look at verse 27: we are talking here about Israelite religion, at least in its original context. But Christians have read this to be about Jesus, and its celebratory tone translates well to any triumphant occasion.

Maybe You Should Think About: You know that kids’ song based on verse 24? Maybe you should sing it? Maybe you should sing that, joyfully and triumphantly, as the kids parade in with palm branches. That seems like just the right tone to set for a Palm Sunday procession.

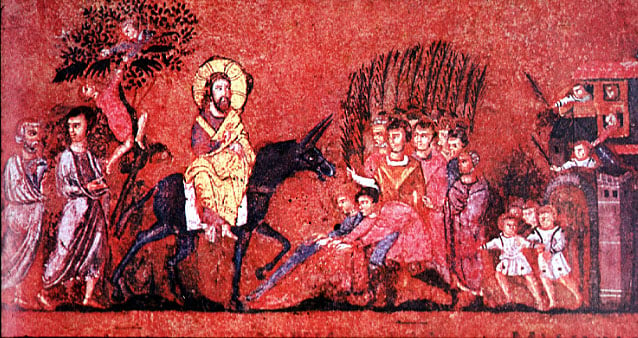

Mark 11:1-11, John 12:12-16

What It’s About: Here we have two stories of Jesus’ triumphant entry into Jerusalem—one from Mark, and the other from John. And they’re somewhat mixed up! The one from Mark is longer and more ornate and the one from John is shorter and has bumbling disciples. Sometimes the old truisms don’t hold true.

What It’s Really About: This is really about setting the scene for Jesus’ conflict with the authorities in Jerusalem. This is really as “messianic” as Jesus ever gets, with this procession with the trappings of kingship and invocations of the name of David. It’s no wonder that this set into the motions the events that led to Jesus’ death.

What It’s Not About: It’s actually not about palms, really. One of the possible translations here is “straw.” Ever think about having “Straw Sunday?” It doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.

Maybe You Should Think About: Where does this come from? Preachers often spend a lot of time on where this goes—the question of how the crowd can go from this adoration to the rejection that follows in a few short pages. But it’s also fair to ask where all this acclamation comes from. What has Jesus done to precipitate this dramatic welcome? How has he provoked this messianic reception? It’s not completely clear from the text. Why does Palm Sunday happen?