What It’s About: This is a recapitulation of the exodus from Egypt–a remembering of God’s acts of salvation in the past. At the same time, it points to God’s salvation in the present–the present of the writer of this part of Isaiah. Just like when God led the people of Israel out of Egypt, God will lead the exiles back from Babylon to the land they call home. The Christian use of this passage (and many others from Isaiah) adds a third temporal dimension; Christians believe that this passage describes the kind of saving work that God will do (is doing, has done) through Christ.

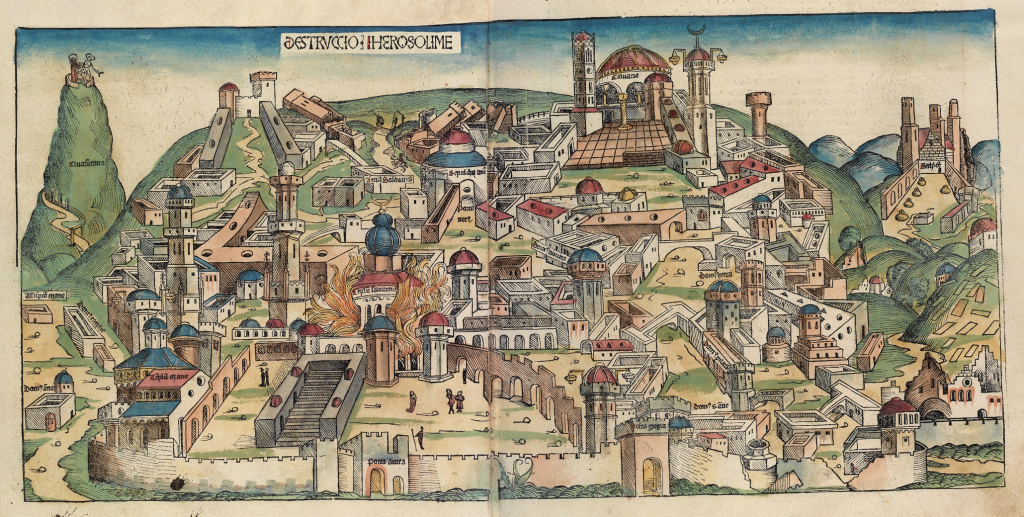

What It’s Really About: Even when Christian theology claims this passage as foreseeing Jesus, it’s important to keep in mind (and honor) the context out of which (and into which) it was first written. That context was the world of 2 Isaiah (Isaiah 40-55), which was written to and for exiles in Babylon. Babylon (the global superpower) had just decimated Judea, destroyed the temple, and carted off the elites into exile. 2 Isaiah speaks to those people in exile, with a backward look toward the ruins of their cities, polities, society, and religion. This passage, then, is a creative synthesis and a profoundly hopeful statement; it looks to Israel’s past to find reason to look forward to the future. It envisions a second kind of exodus, this time not out of Egypt but out of Babylon.

What It’s Not About: It’s not about the sea this time. In the exodus from Egypt (found in, well, Exodus), the great obstacle was the sea. In this case, the great obstacle is desert. The geography of the region is peculiar; most of the space between Jerusalem and Babylon is arid, and not the kind of place you’d like to try to traverse with a large group of refugees. That’s why it’s often called the “Fertile Crescent;” the central space around which the crescent stretches is not fertile at all. So Isaiah is arguing that while God was the one who “makes a way in the sea” in the exodus from Egypt, God will now be the one who will “make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert.” The saving act of God is similar, but the geographical and political circumstances are different.

Maybe You Should Think About: In what way does the story of Jesus participate in or reflect these stories of liberation? How is the kind of salvation or deliverance brought by Jesus similar to–or different than–the exodus from Egypt or the deliverance of the captives from Babylon? Christians have usually insisted that Jesus is another step along the pathway of salvation that God has walked; just as God saved Israel in Egypt, and just as God delivered the captives from Babylon, God is working to deliver and save in the life of Jesus Christ. But these are really very different ways of thinking about what salvation or deliverance means. The first two are communal and particular; the last is significantly more individual and universal (at least in certain ways of thinking). It’s not all that self-evident that these kind of salvation and deliverance are the same; it’s up to Christians to explain why they are, or why they don’t need to be.

Philippians might help to make sense of that.

What It’s About: This is one of the places where Paul rehearses his credentials–the kind of passage Krister Stendahl characterizes as Paul reminding his audience that he has taken all the honor courses. Paul has an impeccable pedigree, as he is quick to remind us; no one is more zealous, righteous, educated, or dedicated than he is. But in this passage, he turns all that good education and experience to a rhetorical flourish–to say that it means nothing in light of his newfound knowledge of Christ.

What It’s Really About: Paul is making a point about righteousness–and it’s one that many Christians will fail to grasp at first read. Righteousness, he says, comes not from something you do (and he reminds us that he has done it all). The righteousness Paul is after is of a different, non-behavior-based sort. It is, Paul writes, “righteousness from God based on faith.” The English is a slightly awkward rendering of slightly awkward Greek, and the “based on” is a compromise rendering of an ambiguous Greek preposition. So all the honors courses in the world won’t gain you this righteousness; you can’t behave your way into it.

At this point the heirs to the Protestant Reformation are standing up and cheering, but there is bad news for them too. Sola Fide is a cornerstone of Reformation interpretation of scripture, and it famously led Martin Luther to view biblical texts like James with skepticism. But there is a significant debate among scholars about what Paul means when he says “faith” (“pistis” in Greek). Christians have usually assumes that this faith is the believer’s faith, and that it consists of just that–believing in things. In that way of reading, this passage becomes a call to reject works of the law and to embrace right belief. But many, many scholars (especially those who are not bound by confessional Protestant traditions) have begun to understand that Paul’s “pistis” often or usually refers to God’s own faithfulness, and/or the faithfulness and faith of Christ. In that way of reading, this passage becomes a call to understand that Jesus’ saving faithfulness has occurred, and that it has opened up a way for gentiles to reach salvation. That way is not the way God made for the Jews; gentiles do not need to follow the law. That would be marching off in the wrong direction.

Notice, by the way, how much sense this perspective makes of the Isaiah passage above. That passage is about faithfulness–God’s faithfulness. God was faithful in the exodus from Egypt, God was faithful in returning the exiles from Babylon, and God has been faithful, in Christ, in opening up a way for the gentiles.

What It’s Not About: It’s not anti-law, it’s not anti-Jewish, and it’s not anti-semitic. Yes, Paul is discounting his own law-saturated pedigree, but remember the audience. Audience, audience, audience. He is writing to gentiles, about the salvation of gentiles. The law is for the Jews; Paul is utterly clear about that, and he views it positively in that light. Just like God makes two ways of salvation, one for the desert and one for the sea, God has a way of saving the Jews (a covenant and a law), and a way of saving the gentiles (Jesus and Jesus’ faithfulness). So don’t read this as anti-law, or, God forbid, anti-Jewish. It’s not.

Maybe You Should Think About: What is Lent about, if what is in view is Jesus’ faithfulness and faith, and not solely our own? What does it meant to walk with Jesus as he makes a faithful journey?

What It’s About: This is the story of Mary’s anointing of Jesus’ feet at Bethany. It’s similar to stories found in Luke 7:37-38 and Mark 14:3-9, but there are important differences, so be sure not to conflate them.

What It’s Really About: This is all about foreshadowing. It foreshadows the treachery of Judas, who in this story is greedy and deceitful, and it foreshadows Jesus’ death and burial. This part of John (chapters 11 and 12) serves as a hinge for the gospel, the point at which the narrative turns to the endgame in Jerusalem. It sets up the stakes with the raising of Lazarus (remembered in this passage), and stories like this one serve to heighten the drama and expectation of how Jesus’ story will conclude.

What It’s Not About: Some of the most fascinating parts of the bible are the parts that are on the shakiest ground. The English of verse 7, “She bought it so that she might keep it for the day of my burial,” adds in words that are not present in the Greek. Your bible probably has a note on this; in the NRSV it is note m, which reads, “Gk lacks She bought it.”

It’s true; the Greek says nothing of the sort. In Greek Jesus’ words can be woodenly translated something like “Said Jesus: leave her alone, for the purpose of the day of my burying, she kept it.” You can see why the extra words were added; the sense isn’t quite complete in English when you rely solely on the Greek. But it’s a useful reminder that translations are always interpretations. And remember: Jesus spoke Aramaic, so even the Greek is already a remembering and a translation.

Maybe You Should Think About: Verse 8. Verse 8 is troublesome; it’s one of those places where you wish that Jesus had kept going, and explained himself. It’s a difficult saying on its face, and it’s difficult to reconcile with, say, the notion of the kingdom of God as an inbreaking phenomenon. But generally, this is probably just a jab at Judas, not at the idea of social and economic justice. Jesus is combating Judas’ self-interest, and not advocating self-interest.