THE DISOBEDIENCE SUTRA

Following the Thread of the Wise Heart

James Ishmael Ford

15 January 2012

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

“Thoreau was a great writer, philosopher, poet, and withal a most practical man, that is, he taught nothing he was not prepared to practice in himself. … He went to jail for the sake of his principles and suffering humanity. His essay has, therefore, been sanctified by suffering. Moreover, it is written for all time. Its incisive logic is unanswerable.” Mohandas Gandhi

“I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. No other person has been more eloquent and passionate in getting this idea across than Henry David Thoreau. As a result of his writings and personal witness, we are the heirs of a legacy of creative protest.” Martin Luther King, Jr.

I was maybe fifteen, possibly sixteen when I first read Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience. I thrilled at the opening paragraph with its pure disdain for external authorities of any sort. In retrospect I realize this is the principal example people cite who want Thoreau to be an anarchist.

Whatever the merits of that analysis, as I continued into the essay I found my own abhorrence of the war our country was then embroiled in was a passion shared with someone a hundred years earlier. If anything his hatred of slavery and as a close second for his vilification, the Mexican war burned even hotter than the rage in my heart.

With each page I slowly came to realize there was something more to this essay than a fantasy of autonomy. His was the lover’s quarrel with the world that many years later I found inscribed on Robert Frost’s gravestone. Thoreau was, by my best read at the time in fact pointing to some deeper truth about individuality and responsibility. Certainly, by the time I’d finished the essay I found myself being invited into some sort of relationship with the world. Precisely what, I wasn’t sure. But, this essay became a touchstone for me, almost a sacred text.

It posited a question that drove me forward. If an individual’s conscience is more important than the will of a prince or in a republic, the majority, what, then, is that conscience? I found the great matter of how we should live in this world, let me be a bit clearer, the great question of how I should live in this world turned, and continues to turn on what exactly the conscience might be.

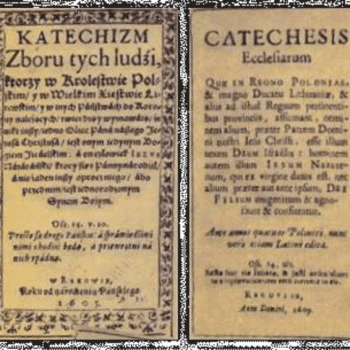

I suggest if Civil Disobedience is a sacred text it is a sutra. Sutra is the term for spiritual texts across the Indian subcontinent, used by Hindus and Jains and Buddhists. Why we should think of Thoreau’s essay, as a sutra is that the word itself, “sutra” shares the same Indo-European roots with sew and suture. Sutra is most commonly translated as thread. I think the deeper meanings of conscience are going to be found by following a thread that is introduced with this essay.

In particular for us, you and me, by following the thread of conscience, of that sense which is more important than external rules, which drives us, guides us, goads us along our way, we may discover something enormously important. What it all is is not immediately obvious. The conscience is a complex thing. As they say, a clear conscience is a sure sign of a bad memory. No doubt it is ambiguous, a mix of what we’ve been taught and other things of mysterious origins. We see that ambiguity on full display in Civil Disobedience.

It becomes clearer only as we follow the thread. First back a bit, and then forward. I feel for us within this spiritual community, the place to begin, the first stich, is with our Transcendentalist ancestors. As those here regularly know, while Transcendentalism was a great literary flowering in New England culture, it was actually primarily a theological controversy within New England Unitarianism, following the shifting of the locus of authority from sacred texts and received wisdom to the direct apprehension of the individual heart and mind. The debates of Transcendentalism were the foundational principles of our liberal religion, applied.

There were pretty much from the beginning in fact two great strands of Transcendentalism that will twist and bind and become our thread. They had to do with differing focus on self and society, in practice the tension was between Ralph Waldo Emerson’s self-culture and Theodore Parker’s social activism. By the end of the 1840s these seemed almost mutually exclusive, looking to the individual heart or mind on the one hand, and living fully engaged with the world on the other. The tension was sufficient that some feared the fracturing of the movement.

In the heat of the Transcendentalist debates, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody felt the need to draw the two strands together. In many ways she really is the mother of Unitarian Universalism. As part of this project she proposed a journal, the Aesthetic Papers, to allow the dialogue to proceed along more healthy lines than they were trending, to pull people together rather than allow them to continue to grow apart. In 1849 the single issue of the journal published what would become a critical examination of how the conscience might be informed by both Transcendentalist visions, knowing both the value of the one, and the value of the many. That essay was Resistance to Civil Government, which with slight editing would be republished generally ever after as Civil Disobedience.

Thoreau opens his essay with that romantic vision of an anarchic utopia, something that rings well with our contemporary libertarians. After tipping his hat to that world without government, he quickly moves to a world that is. He turns to a call for “better government,” government more truly healthy and supportive of the individual. Specifically he warns against majoritarianism and calls for the primacy of individual conscience against the weight of majorities. As such, he challenged the duty of submission to civil government when it offends the moral sense, asserting instead if submission to the rule of law means “…you to be the agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law.” As I’ve suggested he held up slavery and the Mexican war as examples of an evil which any one with a conscience needed to object to, and to refuse to support such things even tacitly, even if that meant prison.

Toward the end of the essay Thoreau points to the source of conscience, when he wrote, “They who know of no purer source of truth, who have traced up its stream no higher, stand, and wisely stand, by the Bible and the Constitution, and drink at it there with reverence and humility; but they who behold where it comes trickling into this lake or that pool, gird up their loins once more, and continue their pilgrimage toward its fountain-head.” These are on their way to the source of conscience. This has been part and parcel of the liberal religious way, to bring the forces of reason and intuition and to go past any revelation, any book, any vote, to see what is. And from that place to take a stand.

From my perspective I think Thoreau went a fair bit up that stream, or, if you will, followed that thread quite a ways. As much an advocate for the individual as he was, as Elizabeth Peabody knew, he also understood we are not alone, we are our brother’s keeper, our sister’s keeper. And ultimately that essay is a call to know our conscience, to grow into it, and to act from it.

Still, it would be two others who would continue on up the stream, up the thread, inspired in part by his call and his pointing, but now bringing us to something also marked with personal sorrow as well as a deeper knowing of the woundedness of our human condition, bringing with that a certain sympathy for us all. And from that place of broken hearts, calling out how we are all bound up together, wounded together by that thread, and healed together by that thread.

First, Mohandas Gandhi, known as the Great Heart. Gandhi had already well embarked on his path of non-violent resistance when he first read Civil Disobedience. It struck him immediately for its power and its urgency, although he was perhaps most taken with the term civil disobedience, from the posthumous title of the essay, which Thoreau may or may not actually have used.

I think there’s no doubt Gandhi’s developed philosophy of satyagraha, soul force, or truth force, is informed by Thoreau’s meditation, if not quite as much as we religious liberals might want. What is certain is that today we can’t look at Thoreau’s essay without thinking of Gandhi, and Thoreau’s conscience without thinking of truth force. Soul force, truth force, here we’re beginning to understand what conscience is, what deeply offended Thoreau about slavery and the Mexican war, and me the Vietnam war, and you, today?

Following the thread from that first call to disobedience articulated by Thoreau becomes, in Gandhi’s hands, richer, and deeper. It is not walking away, wishing just to be left alone. Nor, interestingly, does it call for violence as the solution.

Gandhi schools us, you and me. As he puts it, the purpose in civil disobedience informed by truth force, by our conscience at its clearest isn’t “to defeat or humiliate your opponents, but to win their friendship and understanding.” Here what we are and what we do, are simply one thing. Our actions are our witness. We’ve followed the stream and we can hear the headwaters, we traced up that thread, and this is what we find. It is the way of the wise heart.

There is still more following of that thread. Influenced directly by both Thoreau and Gandhi, and again through Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., tells us “there is within human nature something that can respond to goodness.” It is the same intuition articulated in Thoreau’s essay, enriched by the wisdom of India’s peaceful revolution, by seeing conscience as truth force.

I believe Martin Luther King gets us very close to the headwaters. He takes us up the thread very close to the knot. And he brings home to us the power of Civil Disobedience, the Disobedience Sutra. King refocuses on the power of the truth force within us, of our intimate knowing of the preciousness of the individual. And, a little of why. There’s that lovely image of a cloak of mutuality, which covers us all, that binds us all together as one. King, somehow it feels better to say Martin, Martin sings to us of love and conscience as the manifestation of love, of our deepest intimacy with ourselves, each other, and the whole blessed mess. Out of that great insight he articulated three principles “We must meet hate with love. We must meet physical force with soul force (And, throughout the struggle for justice)…we must follow nonviolence and love….” as one thing. This is the way of the wise heart.

From Birmingham, Martin sang to us of our conscience, and what it truly means. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Martin calls out from the heart of the universe, from the truths of love. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Words to live by. Now, even Martin doesn’t take us to the source. He points, or, rather from his own finding he beckons, he invites. We, each of us, must follow our own path those last steps up the stream, those last inches of the thread to the great knot. Thoreau and Gandhi and King call out to us, it can be done. We, you and I, can find our way.

They point to our conscience, your conscience, my conscience, knowing the intimate reality, we are one family, we are one. This knowing, actually it is more intimate than knowing, is the beating heart of our humanity at its best.

And, it is why when we see injustice, we must act.

The wise heart cannot do otherwise.

Amen.