The question of Zen’s kensho has come up several times in the last few weeks. That’s just the circles I move in, I guess.

Kensho or satori are the experiences (although some will challenge, and for good reasons, the use of that word experience) of insight into our deepest reality. While perhaps most closely associated with the Zen tradition, if there’s a natural insight into reality, then obviously it is owned by no religion.

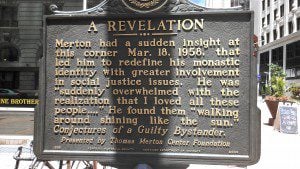

One of the coolest things for me about being in Louisville for the Unitarian Universalist annual convention has been doing a little Thomas Merton tourism. Among the features of this is the only official state marker I’m aware of that celebrates a kensho, in this case, what is often called Thomas Merton’s “revelation,” set up at the corner of Fourth and Muhammad Ali, originally Fourth and Walnut.

Merton’s account, first recorded in his journals, and then slightly polished, in his book Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, is a classic example, of what is called variously an epiphany, a revelation, an experience, a vision, kensho, satori, awakening & enlightenment. Actually, the list goes on. This is his account from Conjectures.

“In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world, the world of renunciation and supposed holiness. The whole illusion of a separate holy existence is a dream.…This sense of liberation from an illusory difference was such a relief and such a joy to me that I almost laughed out loud. And I suppose my happiness could have taken form in the words: ‘Thank God, thank God that I am like other men, that I am only a man among others.’ It is a glorious destiny to be a member of the human race, though it is a race dedicated to many absurdities and one which makes many terrible mistakes: …A member of the human race! To think that such a commonplace realization should suddenly seem like news that one holds the winning ticket in a cosmic sweepstake. And if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun. They are not ‘they’ but my own self. There are no strangers! Then it was as if I suddenly saw the secret beauty of their hearts, the depths of their hearts where neither sin nor desire nor self-knowledge can reach, the core of their reality. If only they could all see themselves as they really are. If only we could see each other that way all the time. There would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed… I suppose the big problem would be that we would fall down and worship each other.”

Now, there are several distinguishing features to these insights that separate them out from all the others we have in our lives. They always point to a deep unity. And they always have some lasting consequence in our lives. Probably the most notable marker for me of those moments I’ve experienced over the years is how they don’t fade in my memory in the same way most all other experiences do.

The Eighteenth century Rinzai master Hakuin spoke of having eighteen major kensho and countless minor ones. As a spiritual director in the Zen way I’ve discovered nearly everyone can recount an experience that falls into the bucket, if for the most part, along the lines of the minor ones. Still, common, common…

Now, I would also add that while a profound sense of unity, and rightness, and everything “falling into place,” is a universal marker of this life transforming moment, or moments, as I said, there are might be any number in our lives, Zen invites us to see through the substance even of this unity, and through minute investigation of the matter to see how the great play of individuals and things include a sense of presence as an individual, of being one with all things, and every bit of it completely without substance. But, as I find this to be, it’s moving on to inside baseball, the particular foci of my own tradition.

The point here is that this totally human experience is profoundly important.

It opens the door to a life that is more authentic than when we don’t know the connections from bones and marrow.

And we need to notice the sharp moments, the moments of forgetting all.

And, we need the hazy moon where self and other are not so clear, where I realize my life is connected deeply, profoundly to others.

And for many it is Zen that has opened this gate, through our particular disciplines of shikantaza, wato, & koan introspection.

For me, endless bows of gratitude.

And, also, then, a great disappointment for many of us has been how kensho doesn’t solve all our problems.

Partially the problem has been how the experience has been oversold. The literature is rife with assertions that having a deep insight changes the world. Philip Kapleau’s masterwork the Three Pillars of Zen is replete with stories of kensho. And it sure sounds like magic.

And particularly at the front end of the great Zen awakening in the late nineteen sixties and through the next decade or so, many of us were totally enthused with the idea of awakening, of enlightenment, of kensho and the whole shebang. Brad Warner speaks of the fascination as a kind of pornography. Other Zen writers and teachers downplay the whole thing. Joko Beck would never speak of awakening experiences as anything but “small intimations.” Other teachers go even farther and suggest kensho is totally alien to the Zen experience and a problem to be avoided.

I find this last bit very sad, a selling of one’s inheritance for a bowl of mush.

Here’s the deal. Zen without kensho is not Zen. It’s that important.

But kensho doesn’t cure cancer. Although it reveals my unity with cancer and hurt and longing as well as with joy and peace.

Instead what we get is a discovery of our ordinariness. And, like for Father Merton, finding our deepest connection.

And, if we have a character disorder, if we are angry or lustful, we continue to be those things.

So, for us, in our time and place, we need to continue to deal with those things as best we can. Here psychology in particular can be helpful. The insights of insight can help clarify what we need to work on, but the work still needs to be done. Although I’m also a believer in the power of vow, and the binding of oneself to communities of practice – and discipline, where the vows are sometimes the expression of our awakening, sometimes, pointers on the way of compassionate action, and sometimes, in the great play of seeing and forgetting, just the rules that keep us from harm and harming.

Finding the right balance is the path.

I suspect one life time won’t prove to be enough…

But, with insight, that’s okay…

It’s the crack in everything that let’s the light shine in…