THERE IS NO GOD And He is Always With You A Search for God in Odd Places

Brad Warner

New World Library, Novato, 2013

A Review by James Ishmael Ford

Brad Warner thinks this might be his best book. I agree.

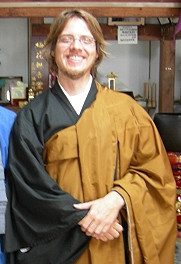

While there are a number of titles Brad Warner could use, Reverend, Sensei, by our Western standards, Roshi, he prefers to go by Brad. I haven’t read everything Brad has written, but a fair amount. And I like to make the minor claim of being the only fully authorized Zen teacher who was willing to blurb his first book Hardcore Zen back in 2003. I’ve always thought he has something to say.

Brad has a delightful biography. While his family traveled and he spent a fair amount of his childhood in Africa, he came of age in Akron, Ohio, where he aspired to be a punk rocker, and succeeded. He then followed his slightly off kilter star to Japan hoping to work in the Japanese monster movie industry, which he did. There he met the Soto Zen teacher Gudo Wafu Nishijima. Nishijima Roshi was heavily influenced by his first teacher Kodo Sawaki, sometimes better known as Homeless Kodo, a reformer of the tradition, who strongly emphasized the “back to Dogen” movement” and a strong emphasis on zazen, seated Zen meditation. A lecturer, author and translator, Nishijima Roshi has kept a distance from the denomination, and has instead established his own independent organization, although organization is probably too strong a term, as the Dogen Sangha.

Prior to going to Japan Brad spent a decade in America studying Zen with Tim McCarthy, a student of another Soto teacher, Kobin Chino Roshi. He also studied briefly with Gyomay Kubose, a Shin priest who taught a nonsectarian Buddhism. After seven years with Nishijima Roshi, the roshi ordained Brad and gave him full Dharma transmission.

Brad broke onto the American spiritual scene with Hardcore Zen, which I’ve characterized elsewhere as Zen delivered with a full-throated scream. While he has mellowed in the intervening years, Brad has made a mark presenting a pretty conservative form of Soto, with a very strong emphasis on zazen (zazen without toys, as some in the Kodo Sawaki Dharma family like to say), and a surprisingly hardnosed insistence on the importance of the full lotus posture, even on occasion suggesting anything less is not zazen, delivered in a take no prisoners style.

His style, as I’ve suggested has moderated. And by the time we come to There is No God, his fifth book, Brad’s voice is more inviting, shows some of the hesitations that come with being knocked around a bit, and in general, I think, is much more compelling. One of the things I’ve always liked about his writing is that he is quite transparent about himself as an ordinary person with a serious Zen practice. He doesn’t play the mystagogue, which, sadly, happens a bit too frequently among prominent Zen teachers. At least as I see it.

The book is framed with some references to his views on what Buddhism is and what ordination in the Japanese style means. Here he places himself at the very edge of the Zen Buddhist community. I’m frankly confused that he starts off in his introduction with a quote from Alan Watts, where Dr Watts points out he isn’t a Buddhist of any sort, but rather is an entertainer. Brad follows the quotation by saying, “This is pretty much how I feel.” Now, I think Brad means he feels similarly to Dr Watts conclusion in that quote, where he says he’s not selling anything, but rather “I just want you to enjoy a point of view which I enjoy.” I think there are going to be those who see the entertainer point as the point.

While I disagree with pretty much his whole analysis of whether Buddhism is a religion, and what exactly it means to be ordained in the Japanese Soto Zen tradition, and how we Zen Buddhists in the West might best organize ourselves, I think he does offer much, and it would be a mistake to dismiss Brad as an entertainer.

The heart of the book, There is No God, shows what I mean.

I find it unfortunate he consistently refers to his perspective on God as “the Buddhist” view, when in fact it is “a Buddhist” view, and I’m confident, a minority report, to boot. That said, his view is compelling. I think powerful. With the exception of his asserting his liberal interpretation of Buddhism is normative (a conceit he shares with Stephen Batchelor, who articulates a powerful reformed view of Buddhism, as well, but unfortunately retrojects his analysis back to the Buddha himself), while not the normative view, it is a perspective with which I find deep resonances. (A last criticism of what I really find a very important book: I also quibble with his masculine by preference language for God. There are good alternatives.)

In the contemporary lexicon, Brad is probably best described as a “new Theist,” taking a naturalistic view, rejecting the idea of a big human in the sky, but seeing the whole may indeed best be described as God. While he shies away from the term pantheist, fearing it too often is seen as materialistic, a term he doesn’t like standing on its own, he pretty much does fit into the pantheistic perspective. I think he and Spinoza might get along very well.

Brad explores a number of aspects of what this naturalistic view of the divine might mean in our lived lives. And he does it with grace and heart. He writes of a murder, and of a friend’s suicide. (Here we find ourselves tied together, as I conducted his friend’s memorial service for his family.) He pushes the reader toward a more visceral insight into what God might mean without appeal to something that exists outside of the world and the human heart, or, as he tends to prefer more traditional Buddhist language here, the mind.

I think this is an important book.

I believe it can be very helpful for Western Buddhists struggling with our natal spiritual traditions, I think it can be helpful for people in the rationalist and atheist communities, offering a larger and more heartful perspective on matters of ultimacy, and, most of all, I think it can be a powerful conversation starter for Unitarian Universalists and others who are largely of a naturalistic perspective, but are haunted by traditional spiritual language.

This is a very good book.

Flawed, like everything else.

Worth reading.

I hope you will.