Three Apples Fell From Heaven

A meditation on the Centenary of the Armenian Genocide

by Janice Dzovinar Okoomian

Delivered at the First Unitarian Church of Providence

April 26, 2015

Paree Louees: Good morning.

Three apples fell from Heaven.

One is for a free and responsible search for truth and meaning; one is for justice, equity and compassion in human relations; and one is for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.

Now, you might recognize these three apples as three of our Unitarian Universalist principles, and indeed that is what they are. And, I am talking about apples today because “Three apples fell from Heaven” is the tagline with which all Armenian folktales end. It’s up to the storyteller to decide what the apples represent and whom they are for.

Today, these apples are falling from the Heavenly tree in order to help me talk to you about the Centenary of the Armenian Genocide in which, between 1915 and 1922, 1.5 million Armenian citizens of Ottoman Turkey were exterminated on the orders of the Turkish government. Four years ago James & I gave a joint sermon on the Armenian Genocide; and I am honored that James invited me to return today for the Centenary.

Today I want to reflect on what I think the spiritual implications of this issue are for us as Unitarian Universalists. And I’m going to invoke those three of our UU principles: the fourth, the second, and the seventh – those are our heavenly apples. I hope to offer some insight on how we as Unitarian Universalists should approach this genocide in its specificity, and all genocides collectively. Certainly, genocide is a social justice issue that demands response; but it is equally a spiritual issue, as perhaps the most extreme expression of our human capacity for evil.

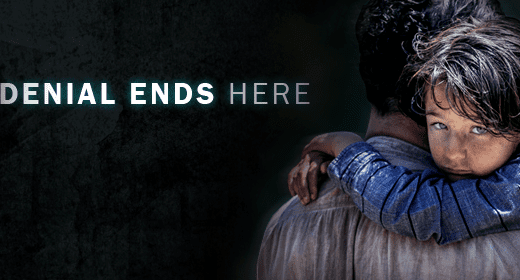

The Armenian Genocide raises for us not only the matter of the genocide itself, which was as horrific as genocide always is, but the problem of the ongoing active denial by Turkey, and by some of its allies (including Israel); and the silence of some of its other allies (including the U.S.).

To be sure, many around the world do recognize the Armenian Genocide, including such luminaries as Pope Francis and Kim Kardashian (and I will leave it to you to determine which of those two has more clout). But of course the important and necessary acknowledgement must come from the Turkish people and government.

Many Turks will say that the claim of genocide is exaggerated; that Armenians died because it was World War I. Some even say that the genocide went the other way around – that Armenians betrayed Turkey by siding with the West in the war, and that they killed more Turks than vice versa. Historians agree that these claims are false and that the record is clear.

Nevertheless, Turkish children for generations now have been taught this false history. Armenian architectural monuments dating back in some cases thousands of years have been destroyed by the Turks, in an effort to eradicate the physical evidence that testifies to the existence of the Armenians in Anatolia long before the Turks arrived in that part of the world.

This year, the Turkish government decided to hold a commemoration of the World War I Gallipoli battle on April 24th. The Gallipoli battle began on April 25th, 1915 and is considered by Turks a great victory in their nationhood and in their war against the West. The decision to commemorate Gallipoli on the date of the Armenian Genocide Centennary is just the latest example of Turkey’s hundred-year denial campaign.

So much for the historical landscape.

Why do the Turks spend so much energy denying what their ancestors did? After all, the Turkish people alive today are not the ones who ordered or carried out the Genocide. Still, to admit that your ancestors tried to wipe out another people means admitting that in direct or indirect ways you are the beneficiary of the suffering of others. The land you own, the wealth you have, your sense of the goodness of your nation and your people – these are all built on the ashes of the people that your people destroyed. You might fear that if you acknowledge the truth, then the victims might come and demand reparations – they might take away your land, your wealth, your nation. And you might fear more deeply that your very sense of self – your soul – might be tainted by the dark stain of injustice.

These fears sound to my ears very like those which prevent some white people in America from acknowledging our white privilege; or the fears that make some men deny that they have male privilege. But facing truths about how we are implicated in injustice is, I believe, exactly where we all need to go, and it’s where the Turks need to go as well.

It would be good for the Armenians to find reconciliation with the Turks, but can you forgive those who harmed you if they don’t admit that they harmed you? No. You can’t. A perpetrator must admit wrongdoing if they are to be forgiven.

Bishop Desmond Tutu puts it like this:

“Forgiving and being reconciled to our enemies or our loved ones are not about pretending that things are other than they are. It is not about patting one another on the back and turning a blind eye to the wrong. True reconciliation exposes the awfulness, the abuse, the hurt, the truth. It could even sometimes make things worse. It is a risky undertaking but in the end it is worthwhile, because in the end only an honest confrontation with reality can bring real healing. Superficial reconciliation can bring only superficial healing.”

But because Turkish people have been so unwilling to face the truth, they and the Armenians have long been at an impasse, locked in a stranglehold of Us/Them from which we can’t find a way out.

Genocide scholars say that the last phase of genocide is denial that it took place. As William Faulkner wrote about the American South, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” So in a very real sense, the Armenian Genocide is not over. I want to suggest that this is true not only for the Armenians, but also for the Turks.

But.

In recent years, something new has begun to happen in Turkey. An opposition movement of Turkish intellectuals and activists has been growing, and on Friday they held their annual ceremonial observance of the Genocide in Istanbul, which was attended by three thousand people, Armenians and Turks. One of the organizers, Levent Sensever, said: “We want to demonstrate to the world that while the Turkish government may not be ready to come to terms with this country’s past, we as citizens of Turkey are ready”. (Levent Sensever of DurDe). There was no violence at this demonstration, although elsewhere on the same day, a group of Turkish students who organized a commemoration on their university campus were tear- gassed and beaten with clubs by police.

These brave souls in Turkey, who are risking their freedom and their lives to speak the truth have taken big bites from the first two apples: “a free and responsible search for truth and meaning” (that’s Number 4); and “Justice, equity and compassion in human relations.” (that’s Number 2).

So perhaps, just perhaps, we are witnessing the arc of the moral universe bending towards justice, as Theodore Parker put it when predicting the abolition of American slavery. I think this will be a long road, but I also believe that there is cause for hope.

There is still one more apple – the Seventh Principle — “Respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.” And in order for us to bite this apple, I need to tell you a story.

This is the true story of a remarkable woman named Fethiye Cetin. Fethiye was born around 1950 in southeastern Turkey, in the province of Elazig, which had been one of the historic Armenian provinces in Ottoman Turkey.

When Fethiye was a law student in Ankara, her grandmother, Seher, disclosed to her that her name was not in fact Seher but Hranoush, that she was Armenian, and that she had been saved from the death march by a Turkish soldier, who literally grabbed her from her mother’s arms, and went on to raise her as a daughter and a Muslim. She became what the Turkish people in her town called “a leftover of the sword”. Hranoush was in fourth grade when the Genocide destroyed her family, but she lived the rest of her life as a good Muslim woman, and became a respected member of her town. She lived to the age of 95 and had numerous children and great-grandchildren. Hranoush forgot her mother tongue and her religion, but she never forgot her family, although she never saw any of them again.

Hranoush chose her granddaughter Fethiye as the one to whom she would tell her story, possibly because she sensed that Fethiye, who was critical of the Turkish government, would be receptive to hearing the truth. Nevertheless, learning the truth about Hranoush’s past turned Fethiye’s world upside down. The details of the story came out over many private meetings, but Fethiye writes “At the time, I didn’t discuss what [my grandmother] told me with anyone else, and neither did I discuss the shock waves it send through my own life” (Cetin 62). Everything she thought she knew about her identity and her family was called into question.

Hranoush hoped that Fethiye would help her find her own parents, Isgouhi and Hovaness. Isgouhi had survived the march and eventually joined Hovaness in New Jersey, where they began a new family. They tried to find the children they lost in Turkey but were unsuccessful. Sadly, Hranoush died before she could find her relatives in America, but Fethiye did eventually find her New Jersey cousins, and she went to visit them, and the graves of her great-grandparents, Isgouhi and Hovannes. There she placed flowers, and then she apologized to them. Her cousin said to her “Fethiye, you don’t have anything to apologize for. You didn’t do anything wrong.” But Fethiye replied: “I am apologizing to the Armenian part of my family on behalf of the Turkish part of my family. Because my Turkish family either were perpetrators, or they were bystanders, or they benefitted from the eradication of the Armenians. So I am apologizing”.

This is, I think, the most extraordinary element of Fethiye’s story, and it takes us right to the heart of the matter. Fethiye could not think of herself as a descendant only of perpetrators or only of victims. She had discovered that she embodied both groups. And there it is right there – the interdependent web of existence, embedded in Fethiye’s DNA. Victim and perpetrator are one, and Fethiye faced this truth with eyes wide open.

Fethiye’s New Jersey cousin Richard also had to come to terms with the fact that it was no longer possible to think of Armenians and Turks as two wholly different and opposed peoples. With Fethiye and all the family at the dinner table, Richard remarked: “I must have been four or five years old when I first heard what the Turks had done to the Armenians. All my life, I’ve been afraid of Turks. I nurtured a deep hatred of them. Their denial has made things even worse. Then I found out that you were part of our family but Turkish at the same time. Now I love all parts of this big family and I’m desperate to meet my other cousins and even make music with them.” (Cetin, 113).

In 2004, Fethiye published a small memoir about Hranoush, called My Grandmother. And after the publication of the book, a tsunami began to form. Fethiye began to receive letters from Turkish people, who wrote to say “I am like you – I have an Armenian grandparent.” In the 11 years since the book came out in Turkish, Fethiye has received hundreds of letters, and they continue to pour into her mailbox. The book has been reprinted seven times and translated into English. And now there is a new book published this year called The Grandchildren, which consists of the testimonies of some of these other Turks about their grandparents. By some estimates, 2.5 million Armenians live as Muslims in Turkey, hiding their ethnic identities but secretly practicing national ceremonies and beliefs. Others have begun to be baptized and “come out” as Armenian. There is sometimes backlash, but it hasn’t dissuaded people from owning the truth of their identity.

So things are beginning to rise and move in the Turkish population that have been still and covered over for a hundred years. It’s not all Turks, and it’s certainly not the government. Not yet. There needs to be continued pressure and protest. But it’s a beginning. And what I think is most important to keep front and center is the sacred knowledge that we are one human people. When we think of ourselves this way, we can’t commit genocide. It’s only when we forget the interdependent web and begin to think in terms of “Us” and “Them” that we humans can do unspeakable things to each other.

Desmond Tutu again: “When we see others as the enemy, we risk becoming what we hate. When we oppress others, we end up oppressing ourselves. All of our humanity is dependent upon recognizing the humanity in others.” It is not only the Armenians who are being held hostage by Turkish denial. It’s also the Turks.

Finally, as important as it is to acknowledge and seek justice for the Armenian genocide in its specificity, it is equally important that we stand up and do all we can to oppose or prevent genocide wherever we see it. Tolerance or ignorance of one genocide helps to make others possible. The Armenian Genocide was the first genocide of the 20th century, but it was both preceded and followed by many others. Here is a partial list (with my hope that I haven’t omitted any) of the genocides that followed the Armenian one: Stalin’s forced famine (1932-33; 7 million people killed); The Rape of Nanking (1937-8; 300,000 people killed); The Nazi Holocaust (1938-45; 11 million people killed); Biafra (1967-1970; 1 million people killed); the Cambodian Killing Fields (1975-79; 2 million people killed); Ethiopia (The Tutsis, 1975-78; 1.5 million people killed); Rwanda (1994; 800,000 people killed); Bosnia-Herzegovina (1992-95; 200,000 people killed); Darfur (Sudan, 2003; 400,000 people killed).

We are all implicated in genocide, whether we be victims, perpetrators, or bystanders, even if we live on the other side of the world or in another time period. When members of our species try to eradicate whole groups of us, the whole interdependent web of human existence is compromised.

So what I hope for us all is that together we face truths that must be faced; that we commit ourselves to justice; and that we open our hearts to reconciliation.

Three apples fell from heaven: one for truth, one for justice, and one for the knowledge that we are all, everyone of us, linked together in the cosmic dance.

Amen.

Work Cited: Cetin, Fethiye. My Grandmother: An Armenian-Turkish Memoir. NY: Verso, 2008.

Copyright 2015 by Janice Dzovinar Okoomian.

Janice Dzovinar Okoomian earned her doctorate in American Civiliation at Brown University. She teaches Women’s Studies and Cultural Studies at Rhode Island College. She has published widely, mostly about Armenian American women’s literature, racial identity, and the body. Dr Okoomian is a member of the First Unitarian Church in Providence.