CLOUDS OF WITNESSES

A Memorial Day Meditation on Abraham Lincoln, the American Republic, and the Great Dream of Human Possibility

James Ishmael Ford

29 May 2016

Pacific Unitarian Church

Rancho Palos Verdes, California

Jan and I’ve been to this nation’s capital four times. One of the few things we’ve done every time was visit the Lincoln memorial. If we go again, one of the few things we will surely do is visit that shrine. And it is a shrine. I believe in a way different than any other monument in our capital it is a shrine, in some genuine sense it is a holy place.

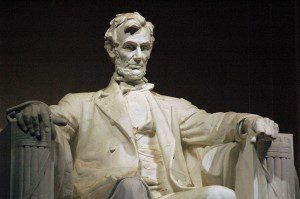

The Memorial is patterned on the Parthenon and like the Parthenon it stands as an enduring symbol of the dream of democracy and freedom. Yes, emphasis on dream. But, imperfect in manifestation, it remains a burning ideal. For me symbolic of that meeting of ideal and actual, within, instead of the goddess Athena, at the heart of this monument sits Daniel Chester French’s statue of a worn, exhausted Lincoln gazing out at the Republic which he preserved and redefined, having washed it in blood and tears, if far from thoroughly enough, of its founding sin.

While many of the monuments in the capital are impressive, I think particularly of the eloquent sadness of the Vietnam memorial, the only other monument in the capital that even approaches the significance of Lincoln’s, to my mind, to my heart, is that of General Ulysses Grant, sitting atop a great war horse, not with a sword outstretched leading a charge, but also exhausted, slump shouldered as if worn down in a torrential rain, or carrying a horrendous burden, significantly with his back to the halls of Congress, facing out, standing ready to defend the Republic, Lincoln’s republic.

For me too many of Washington’s monuments have that sense of Roman triumphalism about them, an aura I find somewhat distasteful. While massive, no doubt, the worn figure of Lincoln within that great monument frozen in white George marble standing at the end of the long reflecting pool sings another song. On the walls flanking the statue are the complete texts of his Gettysburg Address and his Second Inaugural. For me they rank with the Declaration of Independence as the documents that in fact justify America.

Inspired by the one, Lincoln wrote the other two. He really is that important to what it is that our nation might be. Jefferson’s document and Lincoln’s two present the aspiration of what we can be. I should add, present our aspiration in the face of what we too often are.

No doubt among the many, many reasons Barack Obama used Lincoln’s Bible for both his inaugurations, thoughts of Lincoln’s importance to all of us led to that choice. I vividly recall the last time I stood before that statue, a cold and blustery day; the wind whipping right through me. Nonetheless I stood back into the open so I could drink in the whole image. I’m not massively sentimental, but I felt my eyes welling wet.

Today, the Sunday of our Memorial Day-long weekend, as we are beginning a presidential race like no other I’ve experienced in my lifetime, I’d like to reflect on Lincoln as a thread of memory and focus running from what led to that monument, through President Obama’s small gesture as a sort of compass, giving our hearts a true north. These are hard times with uncertain outcomes facing us, frankly none entirely good. Today I want to speak of Lincoln and what he stood for as the spirit that informs our republic, often forgotten, too often, but still, always, to shift the image, a burning coal, the dream of what we might be, and at our best, are.

Unitarian Universalist ethicist and theologian, Ronald Engel frequently used the term “Democratic Faith” to suggest our religious principles and those that informed the founding of the Republic each drawing from the same sources. UU minister Joshua Snyder underscores how this vision which he thinks can be summarized by the slogan of the French Revolution’s call to liberty, equality and fraternity, and which I find summarized nicely as freedom, tolerance and reason, speak to a “larger tradition, of which we Unitarian Universalists are but one institutional incarnation.” I’m acutely aware my deep resonances with those UU principals speaking to an inherent worth ascribable to every individual and our intimation of interdependence as an insight held by many more than simply we UUs. That dual insight of the worth of the individual and our profound interconnection are the essence of a Democratic Faith. And in his weaknesses as well as his strengths, Lincoln can represent it all.

Joshua suggests, “Lincoln stands in this larger tradition even if he does not stand in our own institution. And so,” Joshua suggests, Lincoln’s “views are of interest to us.” Or, should be. I know I read these words in Joshua’s sermon on Lincoln, and I felt a deep recognition. I thought of that cold, cold day staring at Lincoln’s statue, and those deep emotions that bubbled up from I know not where. I do know how I felt a deep sense of gratitude that there are guides for us all around, not only our own exemplars, the Thoreau’s, the Fuller’s, the Emerson’s, the Peabody’s the Parker’s, as precious as they all are; there are so many more who’ve drunk deep from the well of freedom, reason and tolerance, ready to share that wisdom waiting only our willingness to notice, to pay some attention.

One of the things that most impresses me about Lincoln is his raw humanity, how he carried the many hurts that marked his life. On the web I found some of Bill Clinton’s remarks transcribed from a talk, it feels like he was speaking extemporaneously, that touched on Lincoln’s wounded humanity. “It’s really interesting. Lincoln had, you know, serious depression problems. And when he lost a son in Illinois; then he lost a son in the White House; then his wife lost three of her half brothers fighting for the Confederacy.

Then, she suffered all of her trauma. And then he had all the blood of the Union streaming from his decisions.” I read this, particularly “all the blood of the Union streaming from his decisions,” and I felt that same feeling as when staring at his statue in Washington. A trembling. I don’t like it when I can’t quickly put words to feelings. But sometimes, that’s the way it is. And here it was.

When I encounter things like this, stews of complex and often contradictory feelings rising as some image presents I feel a need to look closer. And I think, I feel there is something here. Lincoln not only was informed by great personal suffering, his actions, which continue to seem to me to have been right, nonetheless led to a flood of blood across this country. Many, many died or were maimed, maybe a million people. People were forced to do things against their will, their property taken, their lives impoverished. While others were freed from bondage; best estimate seems to be four million people.

What about that, all of it?

And also, what about the shifts along the way? Lincoln was a moderate, not a radical. Early on he believed the Constitution would not allow the abolition of slavery where it already existed, and his first election platform only called for slavery to be blocked in new territories. I have friends who think he really was just a political hack that got lucky, at least so far as history is concerned. What about that?

I think the “what about that” is how there was a nimbleness in Lincoln’s character, which allowed him to address the changing conditions as they arose. And I consider this a prime lesson. I look inside myself and I try to find that nimbleness. And you know, I suspect I find it in myself only as I hold my own opinions more lightly than I sometimes do. Not without passion, but lightly.

So, for instance, while I was in the position to be one of the principal religious voices in the run up to achieving marriage equality back in Rhode Island, during the struggle I tried hard, not always successfully, but constantly, to recall how those who were opposed to it were not evil. Rather they were caught up in stories of tradition and faith that otherwise had much value, but they couldn’t untangle this bit of blindness and hatred from the wiser parts. And, you know, given different circumstances, different life experiences I could have been one of them. Each of us could have been. The truth is we are all woven of the same stuff, our individual histories only slightly different.

Sharing the same stuff, we all also share the sins of oppression. My hands are not cleaner than anyone else’s. In the case of that struggle for marriage equality in Rhode Island I was just more fortunate in winning just enough perspective to see a bit more quickly than the majority how these patterns of the past were oppressive of human dignity.

And I think that’s so for most all of us in this hall addressing anything that challenges a status quo, any status quo. It’s hard to rise above one’s conditioning and the stories we’ve been told since childhood. And as we launch into this political season filled with so much ill will and so much fear and where one campaign is completely about that fear, we need to recall this. Without good fortune and good friends at the right moment, it’s extremely difficult to gain that broader perspective that allows us to be generous and open. That acknowledged there is a way. I try hard to commit to being open, to being ready to be surprised, shocked and edified, to hold things lightly, passionately but without crushing them. This is a spiritual discipline I find in Lincoln’s personality, and try to find in my own.

My old friend and colleague Tom Schade, for years a minister in our congregation in Worcester, Massachusetts, now like me retired, and like I plan on doing, writing provocative blog postings on our liberal tradition has “come to be drawn by the picture of Lincoln as someone whose positions kept evolving as time and the river flowed toward him. Adherence to principles matters a lot,” Tom acknowledges. But. “I think it more important to be able to see what is the right thing for this moment in time.” Tom sums his point up by quoting one of his mentors. “Sometimes, you have to put aside your principles and just do the right thing.” I read this and immediately I returned to standing in the cold and staring at that statue. This is an audacious assertion. This is a dangerous assertion. And it is the only hope we have of moving beyond the status quo, beyond what was always right to a new right, to a newer and broader vision of justice and care and engagement.

Here we come back to that call to openness, to not following one dogma or another as completely and unassailably true. As an example the late UU theologian and minister Forrest Church observed, “Abraham Lincoln was not a believer in humankind’s intrinsic goodness. Though non-doctrinal in theology, he stood squarely in the Puritan tradition of self-judgment, believing that we are united not by righteousness but by sin.” I think about that, and it causes me to pause. I think our vaunted UU confidence in humanity’s goodness needs to be tempered. For most of us, certainly for me, I think we need a little more self-judgment.

There is just too much evil in the world to pretend something like sin doesn’t exist. Sin is a difficult term for us, I understand. But if sin can be seen as turning away from the good, the openhearted, the insight of the value of the individual and how all individuals are related; then we open the doors to change. Lincoln’s approach was not to vilify his opponents as the only sinners, but to acknowledge his own complicity, our communal complicity in the evils of the world. Nor did he stop there. Instead he offered a next step, toward that nobler possibility which is also our inherent potential, which is always in our hands.

Lincoln’s Second Inaugural address delivered bare months before his assassination is a summary of what I think we can hope for in our lives, both our interior investigations, and in our manifestation of that interiority. It spoke to how we might engage our lives. It spoke to the deep currents that make the American experiment something worth defending, as well as how that should be done.

He spoke to how we might approach the great questions facing our nation and world today, shadowed by terrors and visions of terrors yet to come. Here we are in an era of war and prejudice, of extremes of wealth and poverty. We must be engaged. There is no place to go where we are not connected. Our choices are only how we will engage, passive or active, standing against the current, or using the current. Lincoln, shadowed by his own death, a prophet of Democratic Faith, tells us how we might do it.

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

I read those words, again and again. And the bitter cold of that time in Washington cuts through me once more. And, of course, I tremble. These words speak to a world in turmoil, a broken and bleeding world. And. And. And. They speak to the possibility of something deeper that may guide us through the horrors of it all, toward something dreamt of from the dawn of our humanity. It is the wisdom of a Democratic Faith.

It is our faith.

On this day, this Memorial Day Sunday, surrounded by clouds of witnesses, may we think on these things.

And, I have my hope for us all. An aspiration. A prayer.

May we rise to the occasion; because nothing less than the fate of the world depends upon it.

So be it. Blessed be. And, amen.