I’ve spent this past week at the Russell Lockwood Religious Leadership School, a program to help cultivate lay leadership within Unitarian Universalist congregations. Actually it is open to lay and professional, and of the thirty-two enrollees, three were clergy. I found it an exhilarating experience. If on the exhausting side.

While I was there on faculty, the commitment was for all of us to attend the full program. So, I both witnessed the program and experienced it with very little filtration. And I can report out there is something kind of exciting happening among the UUs. When I first started attending Unitarian Universalist services what I encountered was a pretty hard rationalism, and a beautiful humanist ethic. Obviously it was attractive for me, as I not only started attending services regularly, but I also ended up becoming a UU minister, serving congregations for a quarter of a century, and just now retired.

But this is a spirituality that is dynamic and so given to shifts over the years. And what I’m seeing is that while the humanist ethos is very much there, manifesting in a clear commitment to justice as the experience of love in the world, there is also more emphasis on the mystery and spirituality of love itself. The concern with engagement in the world has never been more urgent. But, it is increasingly grounded in an understanding of how the world is with which I find profound resonance.

So, as I round in both at the end of the leadership school and my own professional ministry I find myself quite optimistic for the Association and its directions. Mostly, anyway.

And then there’s me. I’m having an interesting experience of letting go, and having trouble letting go. Jan, my spouse, has been a librarian for many years, and for the past fourteen years, a deeply devoted part of the team at Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts. While her affection for the school continues unabated, and no doubt they are in our estate planning (you might think along those lines, yourself, should you be so fortunate as to be able to have an estate to plan for), and she does continue to have connections even across the country, primarily doing editing for them, as far as being a librarian goes, she has comfortably let it all go.

Me, not so much.

I am not a believer that you are something other than what you do. To me that isn’t how things are. We are the sum total of many things, but all of them are actions. (Yes, even thoughts and intentions are actions.) And, therefore, my understanding of ministry is that it is what we call in theological circles, “functional.” Of course there are senses in which I continue my ministerial life, but.

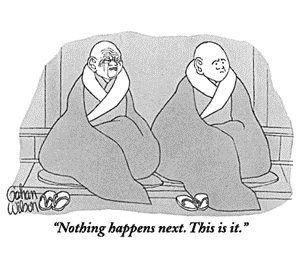

And, among the ironies for me is that I have a complete additional life (not half, but another full one hundred percent) as a Zen Buddhist, and specifically Zen Buddhist priest and teacher. In fact my major project now is helping to foster a Zen group in our new home, Long Beach, California. And it isn’t ending anytime soon, probably. Also, I write, as anyone who follows this blog knows. In fact I’m under contract for a next book, for which I am actively engaged in rewrites. (Working title is Learning the Language of Dragons: Zen Meditation and the Zen Koan, thank you for asking…)

And along with that, of course, I’ve had a spiritual practice exploring the nuances of letting go – that extends over forty years, now. Closer to forty-five for those who like to be precise. So, it is past interesting to me, at how hard I find it at the tailing end of my professional life.

I was talking with an old friend about this. She’s an Episcopal priest. She described how when she arrived at the parish she currently serves, an elderly member of the congregation was a member of the clergy, as well. In fact he had a powerful public ministry, in his day. What she shared with me, and which I’ve been struggling since I’ve heard it was how in that very first meeting after she arrived, his very first words to her were, “I used to be very important.”

I’m surrounded, I’m saturated with the realities of aging. I have a pile of pills I take in the morning, and a couple more I take in the evening. I’m about to schedule a cataract surgery. I look in the mirror and I see an old man. And, these other things are slipping away.

One by one.

So, what makes that worth sharing here?

Well, from the edge of the abyss let me remind you: we are dying. We are all of us dying. Our world is dying. And one more thing. In a very true sense, we are already dead.

And, yes, at the very same time, things are birthing. Many. Beautiful. Lovely. True. And, there is that other sense in which we are alive! And in which that life is eternal.

And at the same time cutting right through it all is the reality we are dying. It’s all an action. It’s all a doing. It’s all a verb.

And. It can be worth our time, a little of it, at least, to face into that fact.

In the Biyanlu, the Twelfth century anthology of Zen koans, the Blue Cliff Record, case fifty-five, “Daowu’s Condolences” we hear how “Daowu and Jianyuan went to a house to express condolences.” In John Tarrant & Joan Sutherland’s translation the story continues…

Jianyuan rapped on the coffin and asked, ‘Living or dead?’

“Daowu said, ‘I can’t say either living or dead.’

“Jianyuan asked, ‘Why can’t you say?’

“Daowu said, ‘I can’t say! I can’t say!’

“On the way home, Jianyuan said, ‘Your Reverence, please tell me right away. If you don’t, I shall hit you.’

“Daowu said, ‘If you like, I’ll allow you to hit me, but I’ll never say.’ Jianyuan hit him.

“Later, after Daowu passed away, Jianyuan went to Shishuang and told him this story. Shishuang said,

‘Alive, I can’t say! Dead, I can’t say!’

“Jianyuan asked, ‘Why can’t you say?’

“Shishuang said, ‘I can’t say! I can’t say!’

“With these words, Jianyuan was enlightened”

For those not familiar with koan literature this is perhaps a bit confusing. Something about death. But obviously also about something else, something that perhaps transcends life and death. Maybe.

Daowu is one of the greats. He features in another of my favorite koans, collected in the Hongzhi Zhengjue, the Book of Serenity, “Who is Sick?” with the lovely question “Why is it that Quanyin (the bodhisattva of compassion) has so many eyes and hands,” and the response “It’s like reaching behind in your sleep and adjusting your pillow.” He pops up a few other places, as well…

In the Dharma Daowu is a great uncle to Soto way in which I practice, his Dharma sibling Dongshan helped to form the school. And I feel in the sweetness of the encounter one can detect a family resemblance here. But within that sweetness there is a relentlessness. He puts the real question to us. What about death? What about life? Why does the Buddha die? I suspect more importantly, why do I die?

Not all that long ago I was talking with some people about why they entered the Zen way. I noticed pretty much all those who had been around a while, more than a couple of years, they had some question about sickness and death, some burning sense of dissatisfaction, of anxiety, of anxiousness in the face of the rush of life and death.

It drove them to the pit of practice, to not turning away, to really, really looking into their hearts. They had become real people of Zen. So, I suggest, the question in this koan is the question of Zen. And even closer to the bone, it is about you and, it certainly is about me.

I find there is something to notice in this little conversation and its follow up. Here the Zen dharma takes a rather different tack than saying the death itself is the point or giving a long sermon on the way out the door. I’ve heard both those stories, and neither resonates with me.

But this story negates neither. Of course it doesn’t spend any time there, either. Instead we get, “I can’t say.”

Me, I like to make much of the word agnostic. As old Thomas Huxley meant when he coined it, I don’t know, and, and I care deeply. This is no passive I can’t say. This is a can’t say that involves every atom in one’s being. It’s the very heart of the Zen life I’ve embraced even as a Unitarian Universalist. Facing in. Witnessing.

There are all sorts of corollaries to this can’t say on the Zen way. Only don’t know. Beginner’s Mind.

Not knowing is most intimate.

I think of my own life, my aging, my beginning to let go of some very important things for me, and how hard and how easy is. And I think of my teachers and the great pointing.

There is a presentation here. And there is an invitation. It is in fact a moment that Jianyuan missed. An easy enough miss. I see how that Episcopal priest made a wrong turn. How easy it is. How I can feel the call of that wrong turn. Grasping after that which has passed.

In life as we live it so much is happening, so much hurt, so much joy, so much dashing about here and there. It’s easy to miss the call from the heart of all that is.

But, also in the case as we receive it, there’s a second chance. Thank goodness for second chances. And third. And fourth…

And so in that second encounter an elaboration of the point to help. Alive, I can’t say. Dead, I can’t say.

And the questions. What would it look like if we just set down our idea of death? What would it look like if we let go of our idea of life?

What then?

What then?