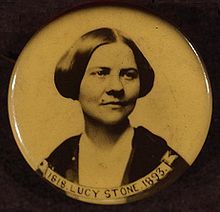

Lucy Stone was born in West Brookfield, Massachusetts on this day in 1818.

She would grow up to become one of the leading lights of the American suffrage movement and a leader for human rights in our culture.

As a child she chaffed under her arbitrary treatment for being a girl. And as she looked at how her mother was treated, she realized the future was not going to be good. Brilliant, she studied diligently on her own, but saw that she needed more formal education. As soon as she could she began teaching, saving her earnings for university tuition. In 1843, with enough money for her first year’s tuition, Lucy was able to matriculate at Oberlin College, the first school to admit both women and African Americans.

While at Oberlin she attended a lecture by the revivalist Charles Finney on the trinity. Lucy was pretty much on the spot converted to unitarianism. Probably not the revivalists’ goal in that lecture. While no longer a trinitarian she wouldn’t formally change from her childhood Congregationalism until she was formally excommunicated in 1851, not for that heresy, but for her vocal and persistent call for abolition. From that point on Lucy found a more congenial spiritual home among the Unitarians.

Back to her Oberlin years, she saw that she was earning about half of what male students were for the various jobs available, and organized a strike. She began to find a taste for public speaking. Lucy and her younger classmate Antoinette Brown organized a women’s debating club. The skills honed there would prove invaluable in future years for both women.

She threw herself into the abolitionist movement, and her first formal employment after college was working for Massachusetts’ Anti-Slavery Society. While quickly emerging as a leader of the movement, her unwillingness to disconnect her visceral sense of the injustices against women from the injustices against enslaved people made her controversial even among her co-workers. Allow me to cite Barack Obama on such things, she was quite comfortable walking and chewing gum at the same time. Others were not. In fact she and Frederick Douglass fell apart over the issue, not reconciling for years. Although eventually they did.

Lucy declared she would never be “ruled by a man.” And so she vowed never to marry, as it meant losing whatever few rights women had to her spouse. However, Lucy was won over by the persistent courting of Henry Browne Blackwell, fervent abolitionist, a co-founder of the Republican party (back when it was the progressive party, mind you), ardent feminist, and, incidentally whose brother married her old friend and ally (and first woman to be ordained a minister) Antoinette Brown, now Blackwell. Together they wrote a manifesto of women’s rights, set up a legal arrangement where she retrained her property rights, and entered into a lifetime relationship. They would have a single daughter together.

After the civil war she turned her attention full to seeking the franchise for women. She joined with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B Anthony, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, and others to form the American Equal Rights Association. As the fifteenth amendment was pushed forward the Association was split by those who supported it and those who felt betrayed women were not included. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B Anthony formed a women’s only National Woman Suffrage Association, while Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe formed the gender inclusive American Woman Suffrage Association. The split would persist for two decades, until finally the two organizations reconciled.

She died on the 18th of October, 1893. She was seventy-five.

The 19th amendment was not passed for another twenty-seven years. But, when it did, it had Lucy Stone’s fingerprints all over it.

It is a wonderment to me she isn’t as well known as most of her contemporaries in the fight. The Wikipedia article on her suggests that because the first major history of the movement was written while the split between the two principal suffrage organizations was still raw, and by an adherent of the other group, she wasn’t given the attention she deserved. And that book, A History of Woman Suffrage became the standard reference for early writers on the subject.

In recent years the omission has been corrected. Lucy Stone is one of the greats.

She deserves to be remembered.

And celebrated.