Despite having been here from before the beginning of the Republic, with the great waves of immigration in the nineteenth century the story of the Irish in America is also very much an immigrant’s story, with all the beauty and sadness that comes with being immigrants. I believe there are few who would be reading this who are unaware of the broad outlines. Prejudice against the Irish as immigrants raged in the middle of the nineteenth century, and actually continued in various ways right to the middle of the twentieth century. We’re all aware of that sign declaring, “no Irish need apply.”

The path into the heart of this country was often ugly. In my life I think of the demonstrations in Southie during Boston’s busing crisis. And how Irish Americans paid for most all the bombs that exploded and bullets, which were fired in Northern Ireland’s Troubles. And before that there were those terrible days during the Civil War when Irish mobs rioted and lynched blacks in New York City. That hard time on the road, as one jaundiced observer tagged it, as the Irish gradually became white.

And the Irish became white. Now there’s a story. I’ve particularly thought about that, how the Irish were not always considered white, and with that, of course, with that as naturally as the dawn follows the night the question: what does whiteness means? Particularly as it matters so much, or has, I desperately want it to be dying as a marker for whether one is on the inside or the outside of the American story of one’s children doing better than oneself. Of course, we know that isn’t the way things are.

So, the invitation: to look at how things are. That’s pretty much the only way things can change. These are, you may have noticed, particularly hard times. This is the first era, perhaps in American history where the young of today, writ large, very well might not do as well as their parents did. And we stand in dangerous times. Our recent presidential election speaks of nothing so much as the despair of many, and the reckless response of those who fear they have nothing to lose. Now nothing lasts forever, not people, not countries. So, who knows how this is going to turn out?

But, as we know dangerous times are also times of change. And so these terrible times are also pregnant with possibilities. And among those possibilities, one is that perhaps, just possibly, if barely, but, I think we can do this. If we as a people take on the invitations that are set before us within the turmoil of our times, we can put a stake in the heart of American racism. And, again, we can fail. It all can go several ways, of course. Hard times also incline one to turn in, and to protect one’s own. We can get more tribal, and I mean that in the worst possible sense.

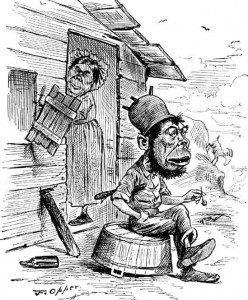

Actually one particularly ugly version of this is how the terrible treatment of the Irish by both the English and the Americans has been turned into a meme “showing” how they were treated worse than African Americans. This is done by drawing a false equivalency between indentured servitude, a terrible thing, and chattel slavery, a horror with no equivalents. But people do draw those equivalencies. Mainly, obviously, to show the historic and institutional mistreatment of African Americans is not so awful. If only they’d be like the Irish. As this pops up in my Facebook feeds from time to time, I know the lie, actually the lies it perpetuates, have not yet been put to rest.

But, we don’t have to turn inward in that unhealthy sense. Rather we can use it rather than being used by it. It can open rather than close. We can open our hearts ever wider. Hard times can remind us that that list of who is us, who is ours, can expand just as easily as it can contract. It has been part of the American genius to include, to gather together.

My father’s family is completely Irish American. It is the only coherent ethnic identity I have. So, I’ve paid attention. Once my people were caricatured as looking more like monkeys than humans. Something anyone who notices and recalls some of those images of former President Obama and his family might find more than interesting. Now one author has described our struggle into the mainstream as selling out those others who were also at the bottom of America’s economic system. Those riots and lynchings in New York were among the poorest of the poor struggling to survive in a tribal way. Another hard truth is that part of our Irish ability to assimilate into something bigger was the fact we really didn’t look all that different from the mainstream of the country at the time.

But, here’s a really interesting fact. Whatever our race we don’t look all that different from the mainstream of our time. Race really is a construct with almost no genetic significance. And while I am proud as can be of my Irish ancestry, and the rest, bottom line, we’re all related, coming as we really all have, from somewhere out at the true homeland, the true Eden, our true dream home somewhere in the vicinity of the Rift Valley. There’s a story.

So, what’s my take away for today, the Feast of St Patrick, the nation’s annual recollection of our Irishness? Well, among other things we of Irish descent should better than most see through the lies of race. Our story is one of overcoming, of becoming larger. Should. Can.

Here’s a bit of that story. We come to this country from many things, actions and situations. Violence, perhaps. Love, you bet. The great Hunger and the choice of leave or die haunts my people. Others came involuntarily. Many, maybe most came dreaming dreams of something better for themselves and their children. That’s true even for those who were here when the Europeans arrived – they, too, come from the Rift Valley. We came poor. More rarely we came rich. We came every color available to our human condition. We bring the cultures, or fragments of cultures that nurtured our ancestors. We bring words and figures of speech. All coming here, to a land of many stories, and one.

We find we need not turn on our immediate or near family to discover the family is in fact much larger. We may have a home in Ireland. Maybe all of us do, in one sense. But we also have a home on the Rift Valley. And that’s even truer. What we know is if one or some of us have done well, then the family obligation is to reach out a hand, and bring another along. ‘Tis the Irish way.

Loving our family, that hand should be held out to as many as possible. That’s the lesson, I feel. To remember the whole family. All of us. All of us…