A MEDITATION ON SPIRITUALITY AFTER RELIGIONS

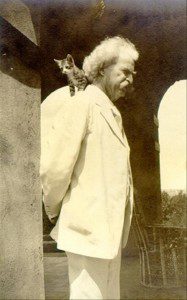

Or, Mark Twain’s Large Dream

19 March 2017

James Ishmael Ford

Unitarian Universalist Church

Long Beach, California

I love Mark Twain. I just love Mark Twain. In fact Jan and I have made Mark Twain pilgrimages twice in our lives. The first time was a tad more than twenty years ago when we lived in Wisconsin, and I served a suburban Milwaukee congregation. During the summer hiatus in our regular services, we took US 90 to La Crosse, and then turned south onto the Great River Road, which traces along the length of the Mississippi. We followed it as far as we had time, which turned out to be to Cairo, about the southern most part of Illinois. However, our main reason for the trip was to stop about two thirds of the way down the river at Hannibal, Samuel Clemens’ boyhood home.

It was resoundingly disappointing. All these years later what I recall most there is the statue of Huck and Tom that stands at the foot of Cardiff Hill. It shows the two boys walking along. We were told it represents Huck trying to slow Tom’s progression forward toward adulthood. I found that a past strange perspective, considering, well, everything about Samuel Clemens and what he thought and what he wrote about. In fact I have to admit the whole experience struck me as being slightly off. As Clemens didn’t really have a lot of good things to say about the town in his lifetime, it occurred to me that maybe it’s only reasonable that down the years the good citizens of Hannibal came to be mostly about smiling at the tourists and taking their money.

The more interesting pilgrimage location for me was the Mark Twain house and museum in Hartford, which Jan, auntie, and I finally got to see about five years ago. Clemens lived there between 1874 and 1891, and wrote many of his most famous books there, including both the Adventures of Tom Sawyer and the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Unlike with our visit to Hannibal, with its air of naked tourist attraction not particularly mitigated by anything else, this was a horse of another color. Walking through the house, and standing in his study, looking down at the same grounds, more or less that he would have viewed over and over again, and then looking at his writing desk where his imagination roiled into some of the great tales to be spun from our American culture that I felt some electric charge, which seemed to me a connection between the man who was the great writer, his insights into the human condition, all of them, and, well, anyone willing to be open to the experience. And I was. I was.

There is so much one could address about him. What I want to reflect on here is Samuel Clemens’ spirituality. To start here is a little bouquet of Mark Twain observations about religion and its practitioners, starting with perhaps his most widely quoted, “Faith is believing what you know ain’t so.” Or, how about his observation about the Bible? He tells us it “has noble poetry in it… and some good morals and a wealth of obscenity, and upwards a thousand lies.” Finally, as to practitioners of my trade he rather dryly noted, “I’ve never heard a sermon in which I could not find some good, though there have been some near misses.”

In some ways this followed his general view of humanity. Here are two examples, again, first the most widely quoted. “Man is the only animal that blushes. Or needs to.” And, a personal favorite, “A clear conscience is the sure sign of a bad memory.” It is this, how shall we call it, perhaps jaundiced view about our human condition that I think most important to notice at the beginning of this reflection.

On the face of it, we have someone who has rejected religion. But, there’s quite a lot more to it than the face of it. In fact, I think he represents the best of that category we now hear so much about, the spiritual but not religious, or, as I’m coming to prefer to call it spirituality after religions.

One could say that while Clemens left his childhood Calvinism pretty early in his adult life, Calvinism never really left him. As a good Calvinist he judged the world, and maybe most of all, judged himself and found the whole thing wanting. But, we also might reasonably ask, he judged the world and himself against what? Buried within that I believe we can find the spiritual that continued to haunt him even as he walked away as best he could from organized religions.

Now, I found it fascinating, at least in the sense of the old joke that if you want to lose your faith make friends with a priest, that throughout his life, Sam Clemens had quite a surprising number of clergy friends. Apparently they were mostly liberal Congregtionalists. For instance there was Joseph Twitchell, one of his closest friends and a friendship for more than forty years.

Another very interesting minister friend was Moncure Conway. Originally a Methodist, he became a Unitarian minister, as well as a leading abolitionist in his day, before leaving for England where he moved ever more independent until becoming minister for a non-aligned non-traditionally theist ethical-humanist congregation. And don’t forget, this is the mid late nineteenth century we’re talking about. It was in fact during those later years that Twain met this remarkable clergyman. They became friends and then life-long correspondents. In fact Clemens trusted him so much that Conway would become Clemens’ literary agent in Great Britain.

A few years ago Independent scholar Dwayne Eutsey delivered a wonderful sermon on Twain and Hinduism, at the UU Fellowship in Easton, Maryland, where he tells us how through Conway, Twain was introduced to Eastern and particularly Hindu thought. In fact two of Conway’s books both with sections on Hinduism were in Twain’s personal library. Between this and Twain’s own experience meeting yogis and other Eastern spiritual guides on his travels around the world, inspires Eutsey to suggest a deeper spirituality influencing Twain than has previously been noticed.

For me this is utterly fascinating. Having broken the strictures of a creedal faith, but in some genuine ways remaining a seeker after truth Sam Clemens was actually able to see hints of something profound in whatever tradition he encountered. And as a world traveler, he had a lot of opportunity.

So, perhaps Mr Eutsey is right suggesting that Twain’s spirituality was influenced by Hinduism in his later years. He certainly makes a good argument. But, more importantly, for me, in his sermon Eutsey also points to Clemens having a deep personal insight that may well have been informed by reading and conversations, but, more importantly which erupted out of Clemens’ heart as something more than an idea, however, good; but rather as an actual, physical experience. Think of a conversion, metanoia, kensho, think of an enlightenment experience.

And, this is the real point. Mark Twain was no doubt informed, if also repulsed by his childhood religion. Then cut loose from the formal affiliations, he was able to wander widely in the fields of the Lord, having deep friendships with several spiritual types, mostly liberal Christians and at least one Unitarian. But, also letting him encounter as equals practitioners of other traditions ranging from Judaism, to Islam, to Buddhism, to Hinduism as well as to see into the hearts of people who claimed no faith in particular.

And, what I find that did, was prime the pump. In this case that pump is the heart. He certainly saw the foibles and hypocrisies in organized religion and its practitioners, and even in those without any particular religion. He also caught hints of things of value along with those failures. Those things, if you will, against which he measured the failures. Along the way of his life filled as it was with joy and sorrow, success and failure, like all of ours, I would add, he found himself ready when life gifted him with something wondrous.

In his 1897 book “Following the Equator,” Clemens writes, “In Sydney I had a large dream, and in the course of talking I told it to a missionary from India who was on his way to visit some relatives in New Zealand. I dreamed that the visible universe is the physical person of God; that the vast worlds that we see twinkling millions of miles apart in the fields of space are the blood corpuscles in His veins; and that we and the other creatures are the microbes that charge with multitudinous life the corpuscles.” In short Twain is saying he dreamt, he felt from somewhere deep within that the universe is God and we are the life force of God. And notice not merely a dream, he called it his “large dream.”

Now the missionary then goes on to a discussion of comparative miracles, and, frankly, I lost interest in pursuing wherever the missionary hoped to go to, or Twain hoped to show us he went. The important point is the dream, the “large dream.” I’ve had a version of it, myself. I bet you have, as well. Or, at the very least have had an intimation of it here and there. I’m sure because it is the song the universe is constantly singing to us into our individual hearts. If we take this large dream together with Twain’s various allusions to a “real” God behind it all we find something. Think of the original spiritual but not religious. Think of Spinoza and Blake and all those who saw the divine in the ordinary suchness of life.

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

All of a sudden instead of a neo-Calvinist certain of his sin but not sure about what he’s sinning against, we have someone who sees us all as connected within the body of God, the primary experience of which all mystics have testified is love, and with that, of course, of course, comes a deep sense of responsibility to each other. That’s the “large dream.”

I think of Mark Twain’s large dream. It seems to me some feeling of love for all the parts was true in him, and seeped into everything he wrote, ironically, maybe, particularly within the harder words that came later. Seeing clear isn’t, of course, seeing all is nice. Clemens saw the shortcomings, and the sins, his own, as well as others. Sin being those actions that deny the preciousness of the individual or our total reliance upon each other.

Here is what I think is the best of spirituality after religions. What Sam Clemens, what Mark Twain calls us to is a relentless facing into the world, to a deep authenticity. Did he come to have a neo-Hindu sensibility? Perhaps. I like to think maybe so. But that doesn’t really matter. What he did come to that we can be sure of, is that we are all of us connected. And, with that for him, most important, that our actions count. This is the secret truth that makes religions true, and which informs any authentic spirituality.

What I believe is from that insight, from that large dream, of that real God and of ourselves as part of it, Sam Clemens called us all to an authentic life. There is no deeper calling for us as human beings. It is the way of authenticity in the face of so much that is false and self-serving. It is the song of hope in the face of hopelessness.

It is about the healing of our own hearts, and the healing of this world. And Mark Twain, of all people, like a prophet of love calls us into that mystery and joy. Something kind of wonderful.

Spirituality after religion.

Amen.