MY ZEN BUDDHIST EASTER

A Sermon

James Ishmael Ford

16 April 2017

Unitarian Universalist Church

Long Beach, California

I served most of my years as a parish minister among our New England congregations. They are generally more traditional in their structure, and, frankly, more comfortable with our Christian origins and heritage than either our Midwestern or Western churches usually are.

What that meant was that I was always expected me to preach about Easter on Easter Sunday, and they tended to want a real Christmas Eve service, candles, lessons, carols, the whole thing. Also, for that Easter Sunday sermon, despite our much vaunted “freedom of the pulpit,” they generally expected me not to go for a bunny rabbits or the “it’s all about the Spring” sermon. They seemed to like watching me twist around and struggle with what this holiday can mean to a crowd that despite liking our Christian origins, today includes humanists, Jews, pagans, Hindus, Buddhists, and, yes, if not traditional Christian, certainly friends of Jesus. You know, us, Unitarian Universalists, the spiritual but barely religious.

And I’ve gotten used to that exercise. So, with some genuine respect for what the tradition is, and acknowledging we UUs very much have a connection to the Christian inheritance, what can Easter mean for us that motley spiritual crew that are barely religious? Of course, we are Unitarian Universalists, so maybe a quick review of what that story is might be in order at the beginning. The Gospel of Mark is generally considered the oldest of the canonical gospels, the time-hallowed stories of Jesus and his ministry. The sixteenth chapter of Mark tells the story of Easter in its most unelaborated version.

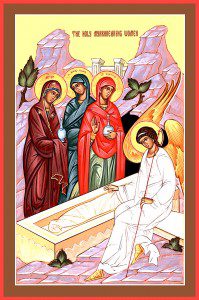

And when the sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome… came… at the rising of the sun (with) sweet spices, that they might… anoint him.. (They were worried who they could get to roll the great stone away from the entrance. However, when they arrived) they saw that the stone was (already) rolled away… And.. (inside) they saw a young man sitting… (there) clothed in a long white garment; and they were (afraid). …(He said) to them, Be not (afraid): You seek Jesus of Nazareth, (who) was crucified: he is risen; he is not here… (Go and) tell his disciples and Peter that he (goes) before you (to) Galilee: there (you shall) see him… And they went out quickly, and fled from the sepulchre; (trembling and amazed): (none saying) any thing to any man; for they were afraid.

That’s it. Now, people don’t like to let things hang quite like they do in this story, and so, somewhere along the line ten more verses are added on. They are largely what would be called “theological,” that is they line out what this story is supposed to mean. As a bit of an aside I find it interesting it’s at these added in parts we get things like handling serpents and drinking poison.

Me, I’m very taken with the actual unvarnished version. In the plain telling it looks a lot like something happened to the women, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James in Mark, but therefore also of Jesus for those who aren’t concerned that he would have siblings, and Salome. Something distressing happens. The tomb is empty. That could be explained easily enough. But, then who is the man in the white robe? And what does that line “he is risen” mean? What does it mean that he would be seen in Galilee? And, most of all there’s that hanging ending. What about that trembling, and amazement, and fear? What about that silence? Talk about an invitation into the world of not knowing, the mysterious source of all learning.

The Zen Buddhist priest Norman Fischer tells of attending an interfaith conference hosted at Gethsemane Abbey a Roman Catholic monastery in Kentucky, perhaps most famous as Thomas Merton, the spiritual writer and social justice activist’s monastery. Norman, a Buddhist who was raised Jewish, was surprised at the number and actually at the graphic quality of the crucifixes he saw everywhere in the monastery. And so, he asked the monks why such a terrible and sad symbol and why so many of them? He wrote of their responses, “Most… said that they did see suffering in the crucifixes, but they also saw love, and they saw redemption, they saw freedom, and they saw joy. The cross wasn’t just sad; it was much more than that, also.”

Then Norman concluded, “This, I suppose, is the theme of Easter.” For me add in that empty tomb, that man making a strange assertion, and the women leaving trembling, and filled with amazement and fear, and yes, silence; and I think Norman is pointing right. The whole pageant of Christianity plays out from this event.

Now, as a Buddhist (of the naturalist and rational sort, by which I mean not inclined to the supernatural and finding reason a great light of human life) I also find in the Easter accounts, particularly Mark’s a hint of something deep and true, part of that treasure trove of human culture. It is about something terribly sad, and at the same time something else, as well. It’s all about our facing into not-knowing, fronting the mystery of our lives.

And it’s personal, real personal. As some here know Jan and I moved my mother and her sister, my auntie in with us shortly after I began parish ministry, now looking on thirty years ago. My mother died five years later. Auntie died the day before Easter two years ago, actually bare months before we came out here to Long Beach. The second bedroom in our condo was supposed to be hers. Actually we still call it “auntie’s room.”

She is very much on my mind today. She was a believer. She believed in Easter, not as a metaphor for something psychological, as profound as I find that can be, but as a simple factual truth. As she lay dying in the midst of Easter tide, through Maundy Thursday, through Good Friday, she knew she was in some very real sense going home, going to a risen Jesus who would embrace her with physical arms. And this marks what I’m saying today. It gives my rationalist, naturalistic Buddhist and Unitarian Universalist heart caution. And it points beyond the mere details of the story, to things I myself believe are true, deepest true.

I believe that our human condition is characterized by hurt. Now, I don’t find a lot of help in the damaged goods view of that hurt, as we get in the idea of original sin, except in so far as we have eaten the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil, and with that dualistic mind have very much cast ourselves into a world filled with pain and desire, loss and longing. But, I also see that our human condition is at the same time always open to something else, to a great healing. In Buddhism it’s called enlightenment, or, and I prefer the word, awakening. And, I believe I also see that sense of awakening in the Easter story. In fact I believe Easter is the Christian story of awakening.

Let me introduce another story that might illuminate what this means. It’s a famous Zen koan collected in the early Twelfth century anthology, the Blue Cliff Record. It’s the sixth story in the collection and it’s all about awakening. It’s really short. Yunmen asked his assembly, “I don’t ask you about before the 15th of the month. Tell me something about after the 15th.” No one spoke, so he responded himself, “Every day is a good day.”

This isn’t a complete non sequitur. The 15th is the time of the full moon, and is a common metaphor in East Asia for the moment of awakening. Also, it probably doesn’t hurt to note that Yunmen lived in harsh, politically unstable times, where armies were on the march and famine and hunger and danger the common currency of the day, So it would be very hard to find the phrase “every day is a good day” meaning “don’t worry, be happy.” No smiley faces in this assertion.

In some schools of the Zen tradition people who’ve been acknowledged as teachers, after a ceremony that takes place in private at midnight, the next day they’re often expected to give a talk on this koan. Also, just a little on that word koan. Koan has entered popular use within our English language meaning a thorny problem, or, for those a little more familiar with it as a spiritual thing, often as a question that has no answer. Neither is what koan really means, at least within the context of its use as part of a spiritual discipline. In that primary sense a koan is a statement about reality, and an invitation into presence. A koan is a pointer to the real, the deepest real, and with that an invitation to come and stand in that real place.

And this is most important. It is within presence we find our awakening, our waking up from the slumber of a life that has been distracted from the most important matters. We slumber with our apparently endless desires. We slumber with our anger and hatred. We slumber as we figure something out as true and defend, fiercely that idea of true, sometimes even to the death. Sometimes our own, too often someone else’s.

Waking up is waking up from all this grasping at wanting and resenting and hating, and knowing for sure, into something else. And, and this is most important: this waking up is also our common human experience. It comes to us as Christians. It comes to us as Jews. It comes to us as Muslims, and as Hindus, and as Buddhists. It comes to us without any religion at all.

Did my auntie find this place? I don’t know. She seemed a bit too sure of the literal reality. But, then, it’s always seeing through a glass, darkly. This is why a psychological definition for this experience isn’t quite on point, either. We’re speaking of what that interdependent web really is, the one, the open, the boundless. And we only ever come to know it through the particular, or more specifically as the particular. You. Me. Eating. Walking. Playing with a child. Standing up to one oppression or another.

And, so, Easter. The Easter of those women. The Easter of auntie struggling for her last breath. The Easter for Jan and me and those long hours sitting at her bedside. The Easter of our friends coming and helping prepare her body, washing it, and dressing her in her Sunday go to meeting dress, and with a shawl closed with one of her favorite dragon broaches.

Easter as this moment, as this mind, as this heart, filled with all its sadness and all its glory. And with our fully opening ourselves to what is, with that complete disruption of what we thought was the way things are. And with that awakening into something new: mystery piled upon mystery. Wonder, and joy, and, yes, absolutely, fear.

And with that back to the story. The Mary’s and Salome experienced a terrible and wonderful moment; a complete disruption of what they thought was so. Where they, each of them, had an awakening, each in their own way, as themselves and no one else, finding the one awakening. Everyday is a good day.

With Easter we’re being invited into a new place, a moment, a stance that can change how we live in this world. I find Easter is a response to the invitation to not turn away from any part, the hurt, the agonies, the failures, the sweet and joyful moments. To open up, and to open up more, until even death is just a part of the mystery.

Find that, and then, the stories tell us, there is a new birth. Like Spring. Like Easter. Like the mind of Easter. Like the heart of Easter.

Amen.

And, absolutely, Hallelujah.