“He was nobody in particular, yet everybody all at once.”

— Conrad Hyers

It is said that the Irish god Manannan mac Lir likes to travel in disguise. He roams from town to town, sometimes entertaining kings with heavenly music, other times baffling onlookers with clumsy feats of buffoonery. “One day I am sweet, another day I am sour,” he declares, as if to explain away his conflicting reputation as both wiseman and fool. His disguise is a familiar one: a hat full of holes, shoes that squish with puddle water when he walks, threadbare striped clothes, a cloak of many colors that shimmers like mist in the sun. It’s a wonder we don’t recognize him immediately. Figures like him have been with us since the beginning, holding up a funhouse mirror to our ordinary lives, mocking our heroes and transfiguring our bums. In short, Manannan mac Lir is a clown.

Clowns need no introduction, says professor of religion Conrad Hyers in his book, The Spirituality of Comedy. When they appear on the scene, everybody recognizes immediately what they are. “There are clowns who are silent and clowns who are subtle, but there are no incognito clowns.” And yet clowns are, by definition, difficult to define. Almost defiantly contradictory, they take upon themselves the myriad aspects of human society and human nature, throwing all of these elements together in astoundingly irreverent and incongruous ways. “In a kaleidoscopic identity,” Hyers writes, “the clown is many people and many moods, formed and reformed out of the same disparate pieces of humanity.” The clown is the Everyman, recognizable despite or, more accurately, because of his make-up and his mask. The clown is the familiar stranger: the god who travels in disguise under an assumed name, yet whose reputation always precedes him.

Big Shoes To Fill: A Walking Contradiction

Over the past few months, we’ve watched this pattern of embodied contradictions and oscillating opinions play out in real-time as a Creepy Clown Epidemic took the American media by storm. In earlier articles, I traced the evolving nature of this phenomenon — from the Phantom Clowns of urban legend, to the mischievous Stalking Clowns confounding police, to the public backlash and its impact on the professional clowning community. As media coverage returned again and again to this strange but eerily familiar figure, interpretations of the Creepy Clown’s meaning have swung back and forth, each new claim reacting against and

building upon those that came before it. Were the clowns real, or just a hoax? Old urban legend, or new media meme? A coordinated effort by marketers, or a grassroots trend of rumors and copycats? Attention-seekers, or anonymous pranksters? Political commentary, or frivolous distraction? Harmless fun, or serious threat? Criminals, or victims?

The answer, of course, is all of the above…. and then some. “Clowns are not ‘simply’ anything,” Hyers writes. “The clown as ‘Everyman’ is the representative of the many-sidedness of our existence and the tensions between sides — not any side or set of characteristics. The clown is omnivorously human.”

This undiscriminating lust for life in all its forms can itself be disturbing (think: the exaggerated mouths and the smiles full of sharpened teeth in so many of today’s creepy clown Halloween masks). There is something unsettling about the clown’s willingness to poke fun at anything, to upset the status quo. We might wonder: is nothing sacred? Yet throughout history, the spiritual role of the clown has always been that of trickster, the Wise Fool who can challenge social norms and bring the shadow-side of ourselves and our community out into the open to be confronted, laughed at, integrated and transcended.

In his exploration of the clown as a cultural and spiritual figure, Hyers notes that there are two distinct manifestations of the clown as a mediator of opposites. The more “complex and ambitious” type of clown, Hyers writes, is the solo clown, who brings these opposites together in his own person and contains the tension of polarity within a single figure. The motley, multi-colored outfits of these clowns speak to this radical inclusivity of contradiction. “If they wear oversized shoes, they will like as not wear an undersized hat. If they give themselves a gaudy smile, they will probably also add a tear. If they are graceful one moment, they will likely be jerky the next.” They might take exaggerated care to tiptoe across the stage, only to trip noisily at the last minute; or precisely measure the swing of their giant hammer, only to miss the nail and smash their thumb instead. One day sweet, the next day sour.

But there is another kind of clowning: the comic duo. Here, polar opposites are exaggerated and separated, embodied in two different characters who are nevertheless bound together, played against one another to hilarious effect. From the Koshare spring-summer clowns (sprouters of grain) and the Kurena fall-winter clowns (maturers of grain) of the Jemez Indians, to the

suave Whiteface and clumsy Augusto of the medieval French pantomimes, such pairs are well-known throughout history. If one is tall and thin, the other will be short and stocky. If one is a wild risk-taker, the other will worry and fret. If one is restrained in word and deed, the other flails about and never shuts up. We see these odd couples everywhere in modern times, too, in comedy pairs like Harpo and Groucho Marx, Laurel and Hardy, Abbott and Costello, Penn and Teller, Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, Simon Pegg and Nick Frost, Troy and Abed… the list goes on and on.

To these pairs, we might add: Patch Adams and Pennywise — the “caring clown” and the “creepy clown” of modern American culture. Perhaps we need look no further to explain the Creepy Clown phenomenon than our culture’s changing view of the clown, from the ambiguous trickster of sacred ritual to mere kids’ entertainer:

Before the early 20th century, there was little expectation that clowns had to be an entirely unadulterated symbol of fun, frivolity, and happiness; pantomime clowns, for example, were characters who had more adult-oriented story lines. But clowns [are] now almost solely children’s entertainment. Once their made-up persona became more associated with children, and therefore an expectation of innocence, it made whatever the make-up might conceal all the more frightening.

Everywhere we find them, clowns are walking contradictions, polarities set in dialectical motion so that we may (re)discover our own wholeness. “Our whole being is put joltingly together by the simple device of slapping opposites against one another,” writes Hyers. With our recent overemphasis on the innocent fun and “light side” of the Caring Clown, perhaps it was inevitable that the darker Creepy Clown would eventually come calling.

One Clown, Two Clown, Red Clown, Blue Clown

But why now? There is something unique about the Creepy Clown Epidemic this year. Although the cycle of clown sightings has recurred fairly regularly since at least the 1980s, there seems to be a deeper sense of urgency, uncertainty and anxiety that has driven this fall’s hysteria.

You don’t need to scratch very far below the surface to discover what it is. Almost from the beginning, commentators have noted the strong parallels between the Creepy Clown hype and the American presidential election, in which many aspects of an increasingly polarized and dysfunctional political system are on full display. Art and film often anticipate and illuminate these trends through their social commentary. Take, for instance, the recently-released Rob Zombie horror movie, 31, which one reviewer describes as “perhaps unintentionally relevant” in the current climate:

[T]he free-loving carnies and the carnage-loving clowns all arguably ought to be on the same side, as they’re at the same level of income, and loosely connected to the whole notion of traveling shows. But they’re not, and indeed, it’s partly because some on the clown side are racist, sadistic, abusive, horrible people. Regardless, though, they’re all being played by rich jerks for some minor amusement, and even once they realize this and have a chance to break the cycle, or heaven forbid, fight the actual system, they can’t stop. They just hate each other too much, while the rich go back to their rich lives unburdened.

Robert Bartholomew, a sociologist at Botany College in New Zealand, links the rise in creepy clowns to two rising forces in the US: social media, and a fear of otherness. “Social media plays a pivotal role in spreading these rumor-panics which travel around the globe in the blink of an eye,” he says. “They are part of a greater moral panic about the fear of strangers and terrorists in an increasingly urban, impersonal, and unpredictable world.”

Politicians have often played on the fear of otherness to rally their base and “get out the vote” on election day. We might even see in the Republican and Democratic candidates an echo of the tragicomic duo, a pair of opposites vying against each other, each one “playing the mask” of political showmanship while also trying to radiate personable authenticity. All of this might explain why Loren Coleman, who posited the Phantom Clown Theory, notes that creepy clown appearances often coincide with the election cycle.

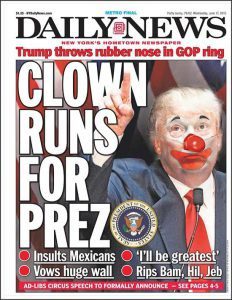

Still, this year’s election season has been one of the most vitriolic in recent history, with one candidate in particular invoking (and provoking) xenophobia, racism and misogyny as defining aspects of his campaign. For some, the explanation for this year’s creepy clown craze can be summed up in two words: Donald Trump. Yale School of Drama professor Christopher Bayes describes Trump as “all illness and artifice,” saying, “There’s something poison there. It feels malignant, and it freaks us out.”

Still, this year’s election season has been one of the most vitriolic in recent history, with one candidate in particular invoking (and provoking) xenophobia, racism and misogyny as defining aspects of his campaign. For some, the explanation for this year’s creepy clown craze can be summed up in two words: Donald Trump. Yale School of Drama professor Christopher Bayes describes Trump as “all illness and artifice,” saying, “There’s something poison there. It feels malignant, and it freaks us out.”

With his uncanny appearance — the fake spray-tan, the wild orange hair, the gaudy sense of fashion, the overblown blustering and weird gesticulations on stage — Trump is the quintessential creepy clown. Equally preoccupied with stoking fear of outsiders and resentment towards insiders who’ve supposedly rigged the system against him, he is not easily categorized according to our usual understanding of political and cultural identity. Instead, he hides behind a mask of populist “everyman” rhetoric to conceal crass self-interest and, perhaps, something even more sinister. In light of numerous allegations of sexual assault, including the rape of a 13-year-old girl and his possible connection to drug-fueled sex parties with underage teens, it’s hard not to see Trump as the “killer clown” who leers at children on the playground and tries to lure them into the woods. Even his caught-on-tape boasting about how his celebrity allows him to assault women — “When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything.” — seems like a sickening callback to the pedophile serial killer John Wayne Gacy’s confession, “You know… a clown can get away with murder.”

Clown as Savior and Escape Artist

How do we rid ourselves of these creepy clowns, real and imagined?

First, it might help to know that much of the Creepy Clown hysteria is driven by media coverage and, like all such trends, it will eventually die down on its own (especially once Halloween and the election are over). Professor of psychology at Evergreen State College, Bill Indict explains, “That’s why it comes in waves. The media propagates it, creates it, feeds it and at a certain point, gets tired of it. The media then digests it and eliminates it. And just as quickly as it started, it’s over.”

We shouldn’t necessarily see this as a criticism of the media’s short attention span, however. After all, that is the clown’s deeper spiritual and psychological role in society: to help us confront our own contradictions, bring them to consciousness, and integrate them. Hyers writes:

What we are reluctant to acknowledge, but what the clown fixes on, is that we are composed of and dream of contraries. We fantasize about complete freedom and complete security, rugged individualism and social harmony, amorous adventures and marital bliss, higher wages and lower prices, something worth fighting for… and peace and tranquility.

The ever-shifting media narratives — about clowns, and about everything — can guide us through a process of navigating these contradictions, swinging from one perspective to another, discovering the complexity of the stories we tell about our all-too-human lives. Hyers notes that clown performances often end with the clowns being chased off stage, driven out of the shared community space and sent scurrying back into the mists of chaos from which they came. “What has been welcomed so clamorously, must also be put to flight somewhat ingloriously,” he writes. “The clowns who have indulged us vicariously, must also vicariously pay a price for their profanities. The scapegrace becomes the scapegoat.”

But at the heart of this process is a longing for wholeness and a renewed sense of unity. With his colorful patchwork antics, the clown reconnects “the many fragmented shades of our existence, if only by tossing them laughingly side by side and calling their ephemeral combination a link between the heavens and the earth.” Liminality and impermanence are all part of the play. The clown straddles, skips and stumbles over the lines we draw to separate the mundane and the sacred, “mudhead and godhead,” order and disorder, stability and change, inside and outside, life and death.

In this way, the clown is also a psychopomp, leading us through fragmentation towards resolution and the redemption of a richer life. Says Hyers, “[T]he clown resembles a ghostly apparition from the spirit world, paradoxically seeking with grinning death-mask to renew life and revive our slumping spirits.” Why should we be surprised, then, to find ourselves brought face-to-face with this paradoxical figure during the season of ghouls and goblins, when the veils between the worlds are thin and the dead mingle with the living?

So maybe the solution is actually quite simple: to rid ourselves of the creepy clown, we need only rediscover the deeper complexity and ambiguity of the clown as a sacred trickster and spiritual guide. To live more courageously and playfully in the face of our uncertainty. To remember to hold our desire for categories of right and wrong, good and evil as lightly as we can. For though we might try to follow where the clown leads, we cannot hope to pin him down or hold him still. It is only when we stop insisting that the clown be just one thing that he is free to become the multiplicity