My family moved to the small town of Wytheville Virginia when I was in the fifth grade. Until that time, I had lived my entire life in the Midwest. I have fond memories of Wytheville, but it was a rural town and freely mixed religion into the public school curriculum. In the Midwest, school and religion did not mix. Sure we sang Christmas Carols and had holiday parties, but we didn’t read the Bible in class, nor watch fanciful filmstrips full of Christmases that never were.

One of the more memorable of those “fanciful filmstrips” was called The Pilgrim’s First Christmas. I don’t remember a whole lot about it, but I do remember the Pilgrims celebrating Christmas, making small presents for each other, and probably converting a few Native Americans along the way. As a fifth-grader I assumed that this was a true story. After all, they don’t lie to you in school and haven’t people always celebrated Christmas? Wasn’t it all about Jesus at the start with the rest added later?

During my high school years as I became more interested in history I found out that the Pilgrims didn’t celebrate Christmas at all. Not only that, but until the middle of the 19th Century most Americans didn’t either. Christmas as we celebrate it today is a rather “new” holiday. While Christmas has several genuinely old (and often pagan) elements, how we celebrate it today is a rather new development. Christmas is a mishmash of various traditions, both religious and secular.

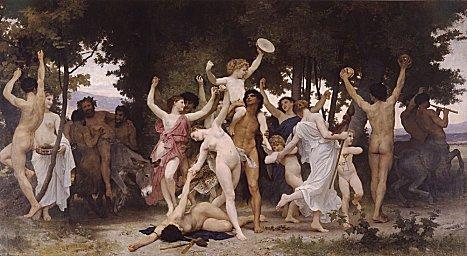

Sure, by the Fourth Century there were Christians celebrating “Christmas.” It wasn’t so much a celebration of Jesus’ birth but a Christian continuation of the Roman holidays of Saturnalia and the January Kalends. Saturnalia featured many of the things we currently associate with Christmas: large meals, holly, mistletoe, gift giving, and abundance. There was no way anyone was going to convince newly Christianized Romans to give up their holiday celebrations, so they became a part of the new holiday of Christmas, a day to celebrate the birth of Jesus.

December 25th wasn’t a date picked by chance either, it was the birthday of Sol Invictus, the Unconquerable Sun, a pagan deity who was very popular with the elite of Rome and those in the army. With Jesus’ birthday on the 25th the feasting, drinking, and gift giving was all allowed to continue, and people could all participate while paying a little lip-service to Jesus.

As Christianity spread across Europe it “Christianized” other winter festivals, adding their pagan elements to a day allegedly about the birth of Jesus. The Norse Yule was turned into Christmas and very little else about the holiday changed. Gifts were still given out, branches continued to decorate homes, and solar imagery still abounded. There was no rush to put up nativity scenes in place of the pagan branches, Yule might have been called Christmas by some, but it was celebrated the same way.

In the 16th Century the first real war over Christmas was fought, and it was a battle between Christians. Despite the yelling to the contrary, there has never been a war against Christmas fought by the forces of secular humanism, liberals, and atheists. Generally the war against Christmas has pitted Christian against Christian. The first salvo was fired by the English Puritans who waged such a successful campaign that Christmas was literally a forgotten holiday in most parts of England and North America until the 19th Century.

In the 16th Century the first real war over Christmas was fought, and it was a battle between Christians. Despite the yelling to the contrary, there has never been a war against Christmas fought by the forces of secular humanism, liberals, and atheists. Generally the war against Christmas has pitted Christian against Christian. The first salvo was fired by the English Puritans who waged such a successful campaign that Christmas was literally a forgotten holiday in most parts of England and North America until the 19th Century.

The Puritans suppressed Christmas because they knew it for what it was, a pagan midwinter holiday. They objected to the pagan imagery, the feasting, drinking, and gluttony. Due to their influence Christmas became a rather localized holiday in the early days of the United States. It was celebrated by the Germans and the Dutch, but was forgotten or seen as a small potatoes by the majority of the population. The United States Congress regularly met on Christmas until 1855, and children in Boston went to school on the 25th up until 1870. The first state to declare Christmas a holiday was Alabama, and that was in 1836!

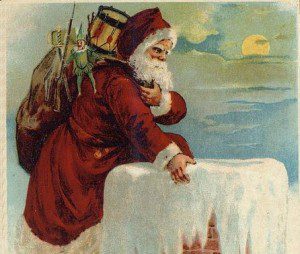

One of the exceptions to this rule was the former Dutch colony, New York. New York City played a major role in establishing Christmas as a national holiday, and none of that had anything to do with Jesus. The Dutch continued celebrating the midwinter celebration of Christmas long after it had gone out of fashion in England. When the Dutch settled the “New World” they brought their traditions with them. One of those traditions was of a mystical gift-giver related to the Turkish St. Nicholas.

The Night Before Christmas went on to become the best known poem in the English language, and its popularity helped to spread the celebration of Christmas. If you were a kid and heard that poem, wouldn’t you want to celebrate Christmas? Santa became the reason for the season, and belief in the North Pole’s favorite resident is a major reason for the spread of the holiday. Without Santa Claus, it’s possible that Christmas would have remained a forgotten holiday in the United States.

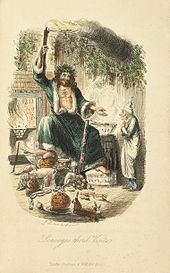

At the same time the United States was wrestling with Santa and adopting the holiday as its own, Christmas celebrations were on the rebound in Great Britain. The great Christmas re-awakening across the pond can be attributed to two things: Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol and Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert. Albert was German, and celebrated the holiday of Christmas just like he did back home in Germany, with gift giving and trees. As a celebrity, he was copied by many in England, and the United States.

Dickens’ tale, while it didn’t invent the modern Christmas, went a long way towards establishing it as a major holiday. A Christmas Carol is not particularly religious, and is mostly a secular take on the holiday. Many of my favorite moments in the story look more like a Saturnalia celebration than the Christmas typically celebrated in Dickens’ day. When you get past the ghosts (one who looks very much like the Roman Bacchus), you have a tale full of gift giving, feasting, family, and drinking. The scene where Scrooge sticks his head out of the window and has a boy run to the butcher shop for him is especially telling. Didn’t it ever strike you as odd that the butcher shop would be open on Christmas? That’s because no one was celebrating it at the time, and if they were, it wasn’t the festival it is today.

Dickens’ tale, while it didn’t invent the modern Christmas, went a long way towards establishing it as a major holiday. A Christmas Carol is not particularly religious, and is mostly a secular take on the holiday. Many of my favorite moments in the story look more like a Saturnalia celebration than the Christmas typically celebrated in Dickens’ day. When you get past the ghosts (one who looks very much like the Roman Bacchus), you have a tale full of gift giving, feasting, family, and drinking. The scene where Scrooge sticks his head out of the window and has a boy run to the butcher shop for him is especially telling. Didn’t it ever strike you as odd that the butcher shop would be open on Christmas? That’s because no one was celebrating it at the time, and if they were, it wasn’t the festival it is today.

Due to Dickens, Albert, and Moore the tradition of a Midwinter holiday was re-established in the 19th Century, but capitalism would play a major role in shaping the holiday. As Christmas grew in popularity, manufacturers began to stress the “gift giving” part of the holiday. The Industrial Revolution provided the Western World with all kinds of goodies that needed to be sold, and Christmas became a prime opportunity to do so. Retailers and advertisers spread the word of Dickens’ Christmas and used Moore’s Santa Claus to sell more toys. The role of capitalism cannot be overstated, Christmas rolled into every nook and cranny of our lives because people wanted to sell things, and then people wanted to get things, and the holiday took off.

Despite the holiday’s initial newness in the United States we have a tendency to romanticize a Christmas past that never was. Christmas can certainly be about faith and family, those are good things, and I’m glad there’s some emphasis on that in the holiday, but it’s never been exclusively about that, and wasn’t designed for it. Christmas is a secular holiday through and through (though dressed in mostly pagan outerwear), and it’s key building blocks almost never reference Jesus or a manger.

There has been a renewed emphasis in some Evangelical and Catholic circles to “Put the Christ back in Christmas,” but the truth is he never was there. The battle has always been to “Put Christ into Christmas.” There is no “back” about it, he’s basically been absent the entire time. The real War on Christmas is being fought by people suffering under the delusion that it’s always been a religious holiday. If there’s a “War on Christmas” it’s being fought by Christians who are trying to rewrite a secular past and replace it with a religious center that never was. The little picture here on the left is telling, it features Jesus inserted into a midwinter setting with the ghost of Odin kneeling beside him. I love that kind of inclusive imagery, but there are many Christians who can’t reconcile themselves to the fact that Christmas is a combination of many things. No one group owns it.

I often find myself straddling a strange fence during the holiday season. I’m certainly not offended when someone wishes me a “Merry Christmas,” nor do I think that the use of the word Christmas in some way walks over my spiritual beliefs. On the other hand I dislike hearing about Jesus being the sole “reason for the season”, when he’s kind of a late addition to the party. In many ways, Christmas is what you make out of it. If, for you, it’s a celebration of Jesus’ birth, that to me is awesome. Have at it, and I hope your Christmas is spiritual and meaningful. On the other hand if it’s a secular celebration of Midwinter, good for you, that’s what it’s always been. Christmas is not yours, or mine, it simply is, and I kind of like it that way.

I often find myself straddling a strange fence during the holiday season. I’m certainly not offended when someone wishes me a “Merry Christmas,” nor do I think that the use of the word Christmas in some way walks over my spiritual beliefs. On the other hand I dislike hearing about Jesus being the sole “reason for the season”, when he’s kind of a late addition to the party. In many ways, Christmas is what you make out of it. If, for you, it’s a celebration of Jesus’ birth, that to me is awesome. Have at it, and I hope your Christmas is spiritual and meaningful. On the other hand if it’s a secular celebration of Midwinter, good for you, that’s what it’s always been. Christmas is not yours, or mine, it simply is, and I kind of like it that way.

*There’s some controversy over Moore’s authorship with some crediting Henry Livingston Jr.