“By proving contraries,” Joseph Smith once declared, “truth is made manifest.” For many, the very phrase “Mormon feminism” is itself a “contrary.” If so, then perhaps Mormon feminism is precisely the kind of place we should look for truth.

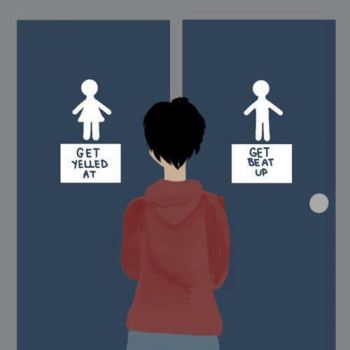

First, some necessary qualifiers. Women hold positions of significant leadership in every LDS congregation, but they do not hold (nor have they ever held) priesthood office in the Church. By definition, women are excluded from the Church’s key decision-making bodies, from ward bishoprics to the First Presidency. Women do participate in governing councils on every level, but always under the leadership of men. How much their voices are acknowledged, furthermore, is largely determined by how much space and influence they are granted by their male priesthood leaders. All-male priesthood quorums are the locations of power and authority; women’s and children’s organizations are “auxiliaries.”

Reflecting on these very real structural challenges, one of my non-LDS feminist students has repeatedly asked, “Why don’t Mormon women go on strike?” There are probably as many different answers to that question as there are women who choose to remain active in the LDS Church. Mormon women stay for social reasons, spiritual reasons, cultural reasons—all the reasons why anyone gets or stays involved with any religion.

For many (not all) women, part of what attracts them to and keeps them within Mormonism is the distinctive brand of feminism deep within the core of the tradition. Although this feminism is fleshed out in relationships, conversations, and movements, it originates in a philosophy that seeks out those elements of the tradition that promote the empowerment of women and the equality of the sexes.

Here I will only consider some of the theological foundations of Mormon feminism rather than the lived experience of Mormon women and feminists. Without wanting to reduce Mormon feminism to ideas—and certainly not presuming to speak for all Mormon women or all Mormon feminists (which includes men)—I want to sketch out four ways in which I see Mormonism giving life to feminism, and feminism giving life to Mormonism. Indeed, at some points it can be difficult to tell where one ends and the other begins.

First, Mormonism redeems Eve. It does so by proclaiming that there isn’t all that much that she needs to be redeemed from. Hers was a “fortunate fall,” a conscious decision that put the wheels of God’s plan of salvation in motion. In the Mormon Eden narrative, Eve is not tricked by Satan so much as she rationally weighs the decision before her, and she chooses the path of knowledge of good and evil with its attendant sin and sorrow, joy and salvation. Mormon scripture and prophets have unequivocally declared that Eve made the correct choice—the one that God wanted her to make—and then got Adam to do the same.

But what to do with God’s curse on Eve: “I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee” (Genesis 3:16). A feminist reading of this passage reveals God’s decree to be descriptive, not normative—the world as it would be, not necessarily how it should be. In a fallen world, the daughters of Eve would be cursed with the slings and arrows of childbirth and motherhood; they would largely be reliant upon men for their security and wellbeing (and thus would have desire toward him); and those fallen men would rule over them, often in a patriarchal and abusive manner. The suffering of women would largely come at the hands of men–as it turns out, Eve’s curse was actually Adam’s curse all along.

Second, Mormonism deifies women as women. I’m not talking about the Victorian pedestal that Mormon men have often placed Mormon women on—a pedestal that in the end resembles more of a prison. Mormons believe in a Heavenly Mother who reigns in heaven side-by-side with Heavenly Father (God). Furthermore, Mormonism proclaims that faithful women will, in the words of early Mormon feminist and Relief Society Presidentess Eliza R. Snow, be “crowned in the presence of God and the lamb” to become “Queens” and “Priestesses.”

To be sure, the doctrine of a Heavenly Mother, though repeatedly affirmed throughout the history of the Church, is largely undeveloped, and LDS prophets have publicly taught that Mormons should not pray to her. Nevertheless, as demonstrated in a recent BYU Studies article, “leaders and influential Latter-day Saints have explored her roles as a fully divine being, a creator of worlds with the Father, a coframer of the plan of salvation, and a concerned and involved parent of her children on earth.” The doctrine of the deification of women is also a central core of LDS teaching and temple ritual. If being a woman is a core part of identity, as most strands of feminism insist, then Mormonism is distinctive if not singular in asserting that women do not have to give up that part of themselves when they go to heaven.

Third, modern Mormonism is responsive to feminism. Though it takes only a few strokes of the keyboard to uncover countless affirmations of Mormon patriarchy, any careful observer would notice that the discourse has changed significantly in recent decades, and continues to evolve. Take for example the language about gender roles in the home. The LDS Church’s semi-canonical The Family: A Proclamation to the World states,

By divine design, fathers are to preside over their families in love and righteousness and are responsible to provide the necessities of life and protection for their families. Mothers are primarily responsible for the nurture of their children. In these sacred responsibilities, fathers and mothers are obligated to help one another as equal partners.

This is the very definition of paradox: fathers preside, but fathers and mothers are equal partners. Similar language is found in the most recent issue of the Ensign, the Church’s official monthly magazine for adults:

The husband’s patriarchal duty as one who presides in the home is not to rule over others but to ensure that the marriage and the family prosper. . . . The husband is accountable for growth and happiness in the marriage, but this accountability does not give him authority over his wife. Both are in charge of the marriage.

Where there may be some degree of message confusion here, on a deeper level I see “proving contraries” in operation. What seems to have emerged in contemporary Mormonism is a paradoxical ethic of egalitarian complementarity. The Church stands firm on the notion of difference rather than radical sameness when it comes to the sexes, and often relies on traditional patriarchal language to express distinctive gender roles. At the same time, it insists on an ultimate and functional equality, particularly within a marriage. Then again, complementarity and difference trumps egalitarianism in the ecclesiastical structures of the church. Thus, the paradox.

Finally, insofar as Mormonism offers a substantive critique of certain forms of secular feminism, it does so by questioning the foundational assumption of the radical autonomy of the individual. This is not so much a beef with feminism as it is with certain fruits of the secular Enlightenment. Mormonism is hardly antagonistic to the individual, but it also insists that the self is not the arbiter of all that is true and good. Community matters, children matter, God matters.

In sum, Mormon feminism manifests the redemption of Eve and Adam (and all their sons and daughters), proclaims the literal deification of women, wrestles with the paradox of equality in difference, and insists on rooting the self in the bonds of human community and communion with God. And that, at least in part, is why Mormon feminism—the seeming “contrary”—is true.