Students in one of my classes wrote about the problem of evil this semester, and some chose to do their final paper on that topic. For many of them, the problem of evil seems to be something simple. Sure, there may be suffering, but all the joys and pleasures of life make up for them.

It seems that for at least some modern Americans, sheltered from the experiences of poverty, famine, disease, war, and other catastrophes that have typified human experience down the ages, the problem of evil isn’t much of a problem.

On the one hand, this depresses me: are some Americans really that insulated from the realities that other people not only have faced but continue to face?

On the other hand, it makes me hopeful: could a day arrive when not only wealthy Americans but most people around the globe find the notion that meaningless suffering was once commonplace hard to imagine, something that could be part of an abstract philosophical thought experiment, but are almost inconceivable as part of real life?

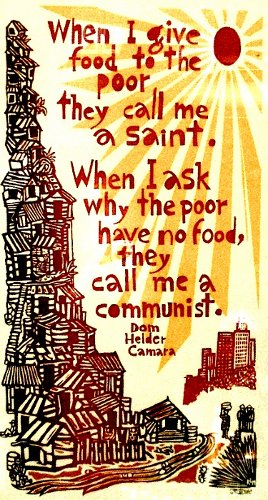

We talked about related matters in my Sunday school class this morning. We had previously started a conversation about the meaning of “daily bread” and the implications of asking for it in a world in which we can simply go buy more than we need, while others would be better nourished than they currently are if they just had what the wealthy throw away. Today I started us off with the famous quote from Dom Helder Camara: “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a Communist.” Such discussions in my class have the advantage of the presence of someone who lived most of their life in a Communist country. While it is clear that Communism as practiced in Eastern Europe was a failure, I question whether that means that the American model of capitalism should be embraced as “the lesser of two evils.” Who says that there can be only these two evils? Should we not be looking for third ways that balance justice and incentive to work in some way, rather than choosing between extremes?

We also talked about the fact that the real issues of poverty in the world are elsewhere, but even within the United States, they are not primarily on the street corner with a sign written on cardboard. They are checking you out when you shop at Wal-Mart, and making and picking the products that you buy at Wal-Mart (using Wal-Mart as but one example, and not as though it were the sole locus of the problem). We prefer cheap items to justice.

The sermon related this all to Christmas. This year alone, Christians will spend far more on presents for other people who have plenty, than it would cost to guarantee that everyone in the world had access to clean water. This doesn’t mean that we should not give presents. We can afford collectively to give the presents that we give and also get involved in providing greater access to basic necessities around the world. The problem is that we do the one but not the other.

Can the problem of evil become a thing of the past? I doubt that there will ever be a time when no one suffers undeservedly. But I think that we genuinely have it within our power to make the world a place where the suffering that has typified most human experience down the ages becomes atypical, where its universality or normativity becomes a thing of the past. It will just require that we actually put our time, money, and effort towards making it a reality.

If we can do that, so that it is not just wealthy Americans but the vast majority of human beings who are convinced that the overall positive experience of living counterbalances the pain we occasionally experience, then I won’t mind students considering theodicy to be a largely theoretical and abstract matter.

But until then, the fact that some can have that impression, while others suffer unimaginably, simply illustrates how serious the problem of evil is, rather than solving it.