Ronald Osborn’s book Death Before the Fall is one that I put off reading for a while, because its title and subtitle seemed to be narrowly focused on things that I was not as concerned about as I once was. But the volume is not in fact just limited to a treatment of things that should be obvious – that animal death and suffering are a reality regardless whether one embraces evolution or some pseudoscientific form of creationism, and that even within the Genesis 2-3 story, if there were no death, there would be no need for a tree of life to prevent it. Rather, Osborn’s book is a wide-ranging investigation of the phenomenon of so-called “biblical literalism,” using this one topic as its starting point and dominant (but not exclusive) example.

Already in the introduction, Osborn offers personal experience combined with sharp insight. Growing up in Africa as the child of missionaries, he got to witness the phenomenon of death first hand to an extent that people in urban America typically do not. And despite being taught that lions became carnivores as a result of the fall, having the chance to see lions, Osborn realized even while still young that the change in both the nature and the physiology of lions to make them carnivores would have to be something that God did, even if it was purportedly done in response to human sin.

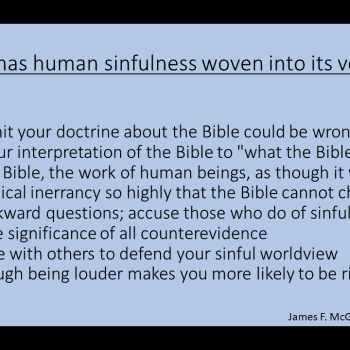

The first part of the book uses the Genesis story to show the problems with so-called biblical literalism. What Osborn writes on p.52 nicely summarizes his outlook:

Accepting arguendo the literalist claim that we can make the chronologies of the two creation accounts perfectly conform on purely linguistic grounds, such a “scientific” reading unfortunately cannot be sustained on narrative grounds without producing a picture of God’s creative activity that is inadvtently comic and that greatly detracts from the beauty and theological seriousness of both creation stories when read on their own terms. I do not wish to make light of the beliefs of others and crtainly not the words of Scripture. But when self-appointed guardians of the faith place senseless obstacles in the paths of honest seekers after truth, I see no reason not to name the folly.

Osborn then goes on to show the absurdity that results from attempts to harmonize Genesis 1 with Genesis 2-3 or to read either chronologically. He also provides quotes illustrating the inappropriate dogmatism of his own Adventist tradition, which of course invented young-earth creationism in the first place.

Chapters in the first part of the book focus not only on careful study of the Genesis story, but also the similar role of literalism in ancient Gnosticism and modern young-earth creationism, and the perspective of important theologians in the Jewish and Christian traditions on the literal meaning of Genesis.

The second part of the book is dedicated to the theological question of theodicy and animal suffering, recognizing from the outset that it is a serious problem, and highlighting that it is not a new issue raised by modern science, but one that the author of the Book of Job already wrestled with, as did other ancient authors. The conclusion returns to the starting point – upbringing in Africa in the Adventist tradition – and emphasizes the need to rediscover Sabbath as a principle not merely of reest but of justice for human and animalkind alike, not as a solution to the problem of suffering but as a response to it.

And so I recommend Osborn’s book Death Before the Fall precisely because it is not only an attempt to show the absurdity and dishonesty involved in so-called “biblical literalism,” nor even some of its more neglected implications, but also offers a robust and compelling alternative which combines careful attention to the Bible, theology, and science, with a practical concern for social justice for all living things.