As the Planned Parenthood “fetal tissue resarch” videos were shining a spotlight on abortion in the US, putting abortion-rights organisations on the defensive and prompting queasiness and sometimes deep thought among pro-choice people, as the Republican Party were once more attempting to have Planned Parenthood defunded, and Marco Rubio was announcing his support for a complete ban on abortion, a very different narrative was unfolding across the Atlantic.

Amnesty International in Ireland, which has become about as pro-choice an organisation as you are likely to find, had representatives holding suitcases outside Goverment buildings, symbolising the women who leave Ireland each year to have abortions in the UK. It was a follow-up to an earlier campaign calling for repeal of the Eighth Amendment to our constitution, which recognises the equal right to life of the unborn. Polls show that there are high levels of support for repeal (though it depends what question you ask), and our extremely consensus-driven politics, no party with a chance of winning seats in the next general election has yet been willing to support the Eighth Amendment in their manifesto.

Why such diametrically opposed trends?

There are differences in the way the two countries pro-life movements do things. There are differences in culture and religion, differences in recent history, and radically different legal starting points (any US pro-lifer worth their salt would take Ireland’s abortion laws in a heartbeat), that account for the completely opposite vectors of momentum.

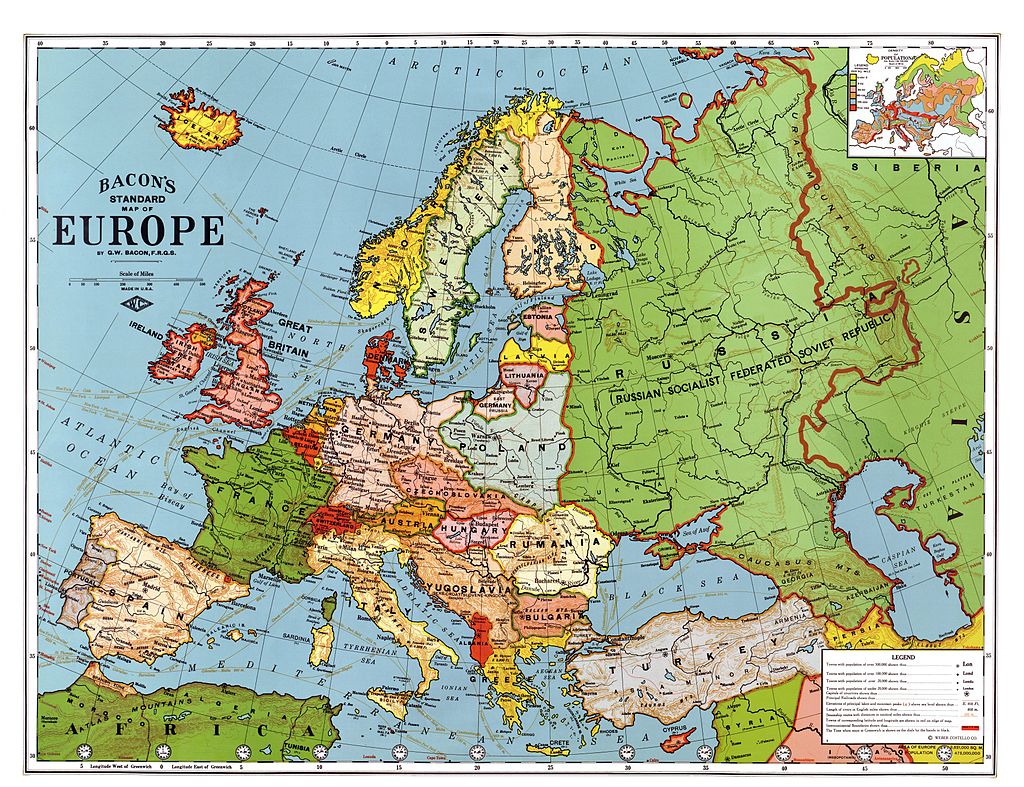

But there’s another possibility – that there is not one abolitionist trend in America, and a different, pro-choice one in Ireland; but a single trend towards what I call the European Equilibrium.

In Europe abortion is legal and easily available nearly everywhere through 12 weeks of pregnancy. After that, countries vary in their restrictions, with most limiting access to abortion as the pregnancy approaches 20 weeks, and a few allowing a woman to terminate a pregnancy as late as 24 weeks — which is right around the time when the baby becomes viable outside the womb.

Even if my wife and I could know every time a fertilized egg fails to implant and then sloughs off when she menstruates, we still would never be moved to mourn the death of a being with intrinsic moral worth. The same holds for fertilized eggs that slough off because a sexually active woman is using an IUD — or, for that matter, because a woman is breastfeeding in the first several months after giving birth. All of these activities lead to the “death” of what really is, at that pre-implanted stage, a clump of cells that is destined not to develop into anything at all.

Nine months after successful implantation, things are very different. I would even say categorically — ontologically — different. How is this possible? I have no idea. All I know is that nearly all of us are convinced that a newborn baby is a person, a creature with intrinsic dignity, worth, and a right to life that the liberal state is duty bound and justly empowered to protect — and yet also convinced that although this same creature possessed the same genetic code from the moment of fertilization, it was somehow of relative moral insignificance in those first few hours and days of microscopic life.

Between those moments (conception and birth) lies a developmental continuum that confounds any and every effort at strictly rational systematization. An abortion at six weeks is worse than one at four weeks. Eight weeks is worse than six. Twelve is worse than 10. And so forth, as we approach fetal viability — at which point, what was once a medical procedure with minimal moral import becomes a matter of murder.

Linker’s argument is completely unfalsifiable, by its structure impervious to any rational analysis or challenge. It is fideism, and its article of faith is the moral intuition that a very young embryo cannot, just cannot, be a human being with full rights and dignity.

Make that intuition just a little bit less unshakeable, allow even a sliver of doubt, and the whole thing comes apart. Why should a newborn baby, with almost no self-awareness, never mind plans, goals or abstract thoughts, be safe from some future, equally certain intuition? How can it be a moral horror to rob such a baby of, in the words of atheist philosopher Don Marquis, ‘a future like ours’ while to rob the same being of the *same future* a few weeks earlier is of little moral consequence? Once we leave some people out of the Enlightenment circle of protection, once we abandon ‘Human Rights for Human Beings’, why not go further? What about people with severe mental handicaps? What about the disfigured? (If it’s not self-awareness that counts, is it the fact that neonates *look* more humanish than embryos?) How does viability make a blind bit of difference to moral status? We do not normally determine human rights based on location. I could not survive in a snowstorm without shelter, a newborn could not survive without constant, comprehensive care, and no unborn baby less than 21 weeks old has yet survived outside his or her mother’s womb – yet that line is retreating all the time.

Is Linker’s position really that it would have been murder to deliberately kill James Elgin Gill in 1987, the year he was born after being in his mother’s womb for 21 weeks and 5 days; but that it would have been something else a couple of decades earlier? The case for the European Equilibrium is not a rational argument.

The options in this world are not and never have been limited to believing either that full moral worth inheres in the unimplanted fertilized egg from the moment of conception or that killing a fetus past the point of viability is a matter of moral indifference. The first position strikes most people who haven’t swallowed the Catholic Catechism whole, or who haven’t forced themselves into the intellectual straightjacket of neo-Thomism, as taking consistency to patently absurd lengths.

…

Between those moments (conception and birth) lies a developmental continuum that confounds any and every effort at strictly rational systematization.

It doesn’t really do anything of the sort. Maybe Linker considers the ‘rational systematisation’ that I subscribe to (human rights for humans, right to life before right to liberty, right to bodily integrity applies to dependent and non-dependent alike) to be taking consistency to patently absurd lengths. I call it refusing to subject other people to the whims of my particular moral intuitions. Once you put your view entirely beyond rational consideration, all you are left with is clashing intuitions that can only be resolved by appeal to only one principle: might makes right.

But supporters of the Equilibrium have plenty of the might that counts in a democracy. They have popular support.Whether it’s the relatively settled view of abortion policy in many (though not all) European countries, or the broad outlines of polling on the question in the United States, there’s a plausible case to be made that the European Equilibrium or something broadly, rather than pro-choice absolutism, is actually the natural resting place of democratic consensus, all else remaining as it is.

It’s not particularly common for people reason their way through a difficult moral problem: far more likely for them intuit their way to conclusions and use reason to justify them. The European Equilibrium allows people who are appalled, or at least squeamish, about dismembering beings that very clearly resemble newborn babies to continue supporting abortion rights. Linker’s intuitions about very young embryos may not be universal, as both Ross Douthat and Alan Jacobs have pointed out, but they’re certainly common enough. Ultrasounds of very early pregnancies do not show all that much: the young embryo does not engage as much emotional or intuitive empathy as the more developed unborn child.

The European Equilibrium would actually be a huge step forward for American abortion laws. But this is my fear: in the long run, it allows abortion to continue apace, allows the millions of deaths each year to go on, in a way that’s a less squeamish, less obviously evil. It makes the horror easier to look away from: and people tend to jump at any chance to be able to look away from horror.

And this is why, deep down, part of me is afraid that abortion won’t be abolished worldwide until the world rediscovers a different way of thinking and of being, until our Secular Age gives way to whatever comes next, and the seemingly unshakeable set of background assumptions about The Way Things Are And Ever Will Be – the Roman Empire of today – comes crashing down. And that is a very, very long term project.

… Or it might take nothing more than an advance in DNA imaging technology which would allow us to project what an embryo might look like when he or she grows up. I hadn’t heard of this, or even thought of it as a possibility, until this morning, after I’d finished writing most of this post. Then I read this First Things article by Richard Stith, which has made me quite considerably more optimistic. Regardless, our task is much the same: hold the line in Ireland, continue the gradual revolution in America, save as many lives as we can, change laws and hearts and minds one by one until some kind of tipping point is reached. No-one saw the fall of the Berlin Wall coming either.

It is a great and urgent task that the abolitionist movement takes on to itself. More soon.