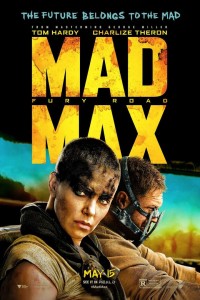

So I saw Mad Max last weekend. I knew something interesting was going on when all my friends started posting on Facebook that they LOVED THIS MOVIE and everyone HAD TO SEE THIS MOVIE. These are people, mostly women, who don’t usually plug action movies. Then I saw that Men’s Rights Activists were having conniptions over it and, well, how could I resist?

Verdict: I loved it. It’s white-knuckle action sequences all the way through, but in a way that heightens the narrative tension instead of dissipating it. The landscape is massive and terrifying, a post-apocalyptic desert that seems to stretch to infinity. The plot revolves around the Citadel, a society ruled by a warlord named Immortan Joe who’s developed a culture that worships violence for its own sake (which conveniently enables him to hoard resources for himself). The “War Boys,” bred from children to be a shrieking, gas-guzzling army, paint their faces like skulls and aim to die in battle so that they can go to Valhalla. The violence portrayed is beyond disturbing; almost immediately we plummet to the very depths of human brutality. Just witnessing it makes you feel a little less like a person. This isn’t just war–this is the bloody, beating heart of war.

So, of course, it got me thinking about the Morrigan.

Or, well–not so much the Morrigan herself, but rather the implications of growing close to a war goddess. I’ve noticed two strains of Morrigan devotion among Pagans: one that reduces the concept of war to one of “honor” and other empty platitudes, and another that embraces violence so wholeheartedly that the idea of the Morrigan having any “soft” attributes at all becomes offensive. I don’t blame people for drifting towards these extremes, though; I’m sure I do it myself. After all, our culture projects contradictory messages. We agree that war is bad, but insist that all our wars are good. We learn as children that hitting people is wrong, but our popular media portrays shooting people as awesome. How many times have characters been established as badass by picking off a seemingly impossible (human) target? None of it makes sense. No wonder we can’t reconcile the two.

So, as Imperator Furiosa raced across the desert, trying to outrun the War Boy army and get Immortan Joe’s sex slaves to safety, I thought about our relationship to violence. The extremes are laid out pretty starkly in the movie: men against women, gasoline against breast milk, death-worshippers against seed-carriers. Almost every character engages in violence, but I noticed a crucial difference: the War Boys fight for the sake of fighting (although Immortan Joe benefits materially), while Furiosa and her cohort fight in order to stop fighting. One side literally worships violence and death; the other wants to nurture life.

It’s folly, though, for a Morrigan devotee to just pick one extreme–looking for fights or wishing for peace–and ignore the other, because the Morrigan embodies both. Maria Tymoczko, writing for the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, describes the Morrigan as a “war goddess feeding on death and nourishing mother whose paps were monuments of the landscape”(1). Rosalind Clark writes that, like other Celtic goddesses, the Morrigan “combines destructive characteristics with those of nurturing, sexual power, and fertility”(2). This paradox is echoed in Pagan writing: Honor Johnson, on OBOD’s website, describes her as “a birth Goddess and a death Goddess,” one of the avatars of the Great Goddess herself; and Stephanie Woodfield, author of Celtic Lore and Spellcraft of the Dark Goddess, explores her role as earth mother alongside her role as war goddess. And make no mistake–if you know what to look for, the Morrigan’s talon-prints are all over this movie. (I’ll give my main example in the comments to avoid giving away a massive spoiler.)

So if the Morrigan embodies both life and death, violence and nourishment, then what does that mean for us?

There’s a saying I like: The more you turn towards the light, the larger your shadow becomes. (I tried to track down the origin and found only a Kingdom Hearts forum, so I really hope I’m not quoting a Disney game here.) We all have the Morrigan within us. We all have the capacity to bring forth life and abundance, and we all have the capacity to lose ourselves in brutality. We’re meant to see Immortan Joe as utterly vile, but I think what’s truly frightening about him is that underneath the monstrous veneer, he’s a human being like us. If greed, power, and a forbidding landscape can wreak such havoc on his psyche, who’s to say you or I would be immune? Think of the people who claim that they would have fought for civil rights in the 60’s, yet think it’s okay for today’s Black men to be gunned down by police. Think of the times you’ve said or done something you regretted, something that you’d previously told yourself you would never do. Violence is an integral part of us all. The ability to see yourself in even your worst enemy is a valuable gift.

But to acknowledge and honor our capacity for violence isn’t the same as condoning or indulging in it. The War Boys, feverish to snuff out their own lives to the tune of a fire-belching electric guitar and a thousand car engines, serve as a ghastly parable of the celebration of violence. When you begin to think violence is good just because a war goddess engaged in it, you begin to shed your humanity.

Which isn’t to say that violence is always overt or obvious. What’s worse: lashing out at someone and bragging about it afterwards, or lashing out at someone and then denying it because it doesn’t fit with the narrative you’ve constructed about yourself? If we run away from our violence, it catches up with us, but if we barrel towards it, we’re engulfed.

So then where’s the middle ground? Well, Buddhist writers have already tackled this subject pretty extensively, so I’ll point you to Thich Nhat Hahn, Sharon Salzberg, Jack Kornfield, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, and Pema Chödrön. Mindfulness is a fantastic tool. You can say hello to your violence, even offer it a cup of tea, without letting it drag you off to some coke party in a skeezy apartment on the other end of town. I like this quote about anger from the Interdependence Project:

You need to keep going inside and re-examining your own motivation and intention. What situation does the anger point you to? Often we displace anger at one thing onto a more convenient target or we simply explode, shooting anger out in all directions, hitting the innocent and the obstructors. What is the wise or skillful way to act?

Here’s a question to ask before you act: Am I about to improve this situation for everyone involved? If the answer is no, then that’s an opportunity to deepen your spiritual practice (even if you can’t salvage the situation). We’re not expected to be our best selves all the time, but striving for it is the only way honor the holy tension within us.

The battle crow and the abundant breast. The bringer of death and the nourisher of seeds. We all embody this paradox. Even the most barren desert can give rise to oases, and even the most verdant field can succumb to poison. There’s no right or wrong in it–it simply is. She simply is. We simply are.

(1) Tymoczko, Maria. “Unity and Duality: a Theoretical Perspective on the Ambivalence of Celtic Goddesses.” Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium. 5 (1985): 22-37. Print.

(2) Clark, Rosalind. “Aspects of the Morrígan in Early Irish Literature.” Irish University Review. 17.2 (1987): 223-236. Print.

CLICK HERE TO “LIKE” PATHEOS PAGAN ON FACEBOOK

Support great Pagan writing by liking Patheos Pagan and Asa West!