I’m not Catholic, but some of my favorite books are.

I came of age during the 80s, the heyday of evangelical youth group culture. By the time I was 17, I’d descended into a Christian subculture of punks, skaters, metal heads, and goths. That felt more like home to me. We had an understanding and appreciation of the darker side of life and asked more questions than we answered. My peers understood what real temptation and real falling looked like, because they were experiencing it themselves and were willing to talk about it.

I was disillusioned with evangelical culture, overwhelmed by the lights and lasers of worship, suspicious of the clever maxims about gratefulness and joy. I needed something deeper, darker. I needed mystery and unapologetic awe, exquisite art on every surface imaginable, the constant reminder that confession is not a fearsome command, but an invitation.

The Way of Perfection by Teresa of Avila

When Teresa of Avila was a little girl, she and her brother used to run away “in hopes of attaining martyrdom,” and she would build little hermitages. A few years later, during an illness, Teresa read the Letters of Jerome, the monk who translated the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate), and decided she should be a nun. But after she entered the Carmelite convent in Avila, it took 20 years for Teresa to experience inner conversion. At this point in her life, she’d been taught by Augustinian nuns, entered the Carmelite order, left due to another illness, and returned once more. I love this about Teresa. I trust a woman who requires that many tries to find her spiritual home. She eventually tired of the worldliness that had crept into the monasteries, so she struck out on her own to build a convent, St. Joseph’s, founded on the two characteristics she believed were essential in a spiritual mature religious order: poverty and solitude. Her reforms inspired her pupil, St. John of the Cross, to push for similar reforms among the Carmelite friars.

In 1565-1566 Teresa wrote The Way of Perfection to provide instruction for the sisters. Who wouldn’t want to read a book with chapter titles like: Why we must avoid our families and how we can find our true spiritual friends?

“I do not know why anyone is in a convent if she is willing to bear only those crosses she thinks she has a right to expect.”

*Drops mic.*

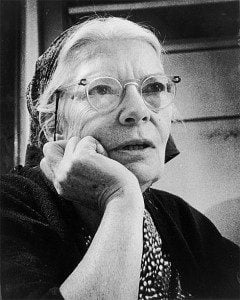

The Long Loneliness by Dorothy Day

“I think the trouble and the long loneliness you hear me speak of is not far from me . . . The pain is great, but very endurable, because He who lays on the burden also carries it.”

Mary Ward, an English nun born not long after St. Teresa established her rule, wrote this. Those three words pack a punch, reminding us of our own long loneliness. At the beginning of her autobiography is a small section called, “Confession,” where she writes, “When one writes the story of his life and the work he has been engaged in, it is a confession too, in a way.”

Dorothy Day was a nonviolent social activist, journalist, Benedictine Oblate, and founder of the Catholic Worker Movement. She loved, served, and defended the poor, and also lived with them in New York City. Dorothy Day was hardcore. Her last imprisonment was a 10 day stint for protesting against the Teamsters Union with Cesar Chavez on behalf of the Farm Workers Union. She was 76.

“There was a great question in my mind. Why was so much done in remedying social evils instead of avoiding them in the first place? There were day nurseries for children, for instance, but why didn’t fathers get money enough to take care of the mothers so they would not have to go out to work? There were hospitals to take care of the sick and infirm, but what of occupational diseases. and the diseases which came from not enough food for the mother and children? What of the disabled workers who received no compensation but only charity for the remainder of their lives? Where were the saints to try to change the social order, not just to minister to the slaves but to do away with slavery?”

Rilke’s Book of Hours: Love Poems to God

Rainer Maria Rilke was born in Prague in 1875 and endured what he referred to as “an anxious and heavy childhood.” His father insisted he got to military school, “one single terrible damnation,” which left him ill and made him a constant presence in the infirmary, providing sanctuary from the cruel bullying and brutal teasing he experienced. Soon after, at 19, he wrote the letters that would be published as Letters to a Young Poet in 1929.

Rilke visited a monastery in Russia in his early twenties. The landscape, common worship, and deep spirituality he encountered became a source of powerful inspiration, and he wrote Love Poems to God during that time. His poems express a deep longing to know God, love him, and comprehend what it means to be loved by a present and living God. He divided the book into three parts, which will greatly appeal to all of us Sick Pilgrims:

Part I: The Book of Monastic Life

Ich habe viele Bruder in Sutanen

“But when I lean over the chasm of myself–

it seems

My God is dark

and like a web: a hundred roots

silently drinking.

This is the ferment I grow out of.”

Part II: The Book of Pilgrimage

Ich bete wieder, du Erlauchter

“I’ve been scattered in pieces,

torn by conflict,

mocked by laughter,

washed down in drink.

In alleyways I sweep myself up

out of garbage and broken glass.

With my half-mouth I stammer you,

who are eternal in your symmetry,

…

It’s here in all the pieces of my shame

that I now find myself again

I yearn to be held

in the great hands of your heart–

Into them I place these fragments of my life,

and you, God, spend them however you want.

Part III: The Book of Poverty and Death

Vielleicht, das ich durch schwere Berge gehe

Since I still don’t know enough about pain,

this terrible darkness makes me small.

If it’s you , though–

press down hard on me, break in

that I may know the weight of your hand,

and you,. the fullness of my cry.