This is Bill.

(courtesy of Pixabay)

What words would you use to describe Bill? Dashing, perhaps? Handsome? Preppy? Skinny? A stick figure? Fair enough.

I bet I can think of a word you didn’t use to describe Bill. I bet nobody said “shorter.” I’m pretty sure nobody said “taller” either.

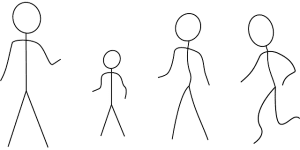

Ah, but what if I told you Bill has three brothers?

(Also courtesy of Pixabay. Bill is second from the left.)

That’s right. Bill is shorter than George, Frank and Stanley. George, Frank and Stanley are taller than Bill.

Oh, but you say, I couldn’t have known that by looking at Bill. “Taller” and “shorter” aren’t qualities Bill has in himself. “Taller” and “shorter” are qualities Bill has in relation to his brothers, or that his brothers have in relation to him.

Wait, so you’re saying that Bill’s status as “taller” or “shorter,” is relative to the size of his sisters? Not something he has in himself?

What are you, some kind of relativist?

Of course you are. Practically everyone is. Because, the fact is, quite a few things really are relative. Peanuts are deadly to some, and not to others. They’re not deadly in themselves. Cilantro tastes like soap to me but not to Rebecca. It doesn’t taste like soap in itself. If people didn’t exist, there wouldn’t be any debate as to whether soy is healthy or poison. It’s only healthy or poisonous relative to us.

Ah, you may ask, but what about morality? Relativism is fine for stick figures, but morality is never relative. Moral relativism is the horror of our age.

Funny you should ask.

There are definitely real, objective moral rules out there. The moral teachings of the Church are not optional for Catholics, and we all ought to strive to live a moral life according to those teachings. But guess what? You have to apply those teachings to your own personal situation, and the Bible and Sacred Tradition don’t spell out exactly how. The Vatican and the Bishops release statements periodically on all kinds of issues, but they can’t tell you exactly what to do in every situation. A lot of applications could be right in some situations, but wrong in others. There is a time to speak and a time to be silent, a time to cast away stones and a time to gather them up.

That’s right. In practice, in day-to-day life where we actually work out our salvation with fear and trembling, morality is sometimes relative: relative to a situation, or to a person, or to your state in life. Applicable to Bill but not to Stanley, and especially not to Stanley’s sister Janine. And this is scary.

We don’t like this, at all. It’s hard work. We have to use our minds, and exercise the virtue of prudence. In my experience, American Catholics like me are scared to death of prudence. We don’t want that Cardinal Virtue, even though it’s the one by which we exercise the other three. You can’t be just, temperate or strong, if you don’t know how to apply justice, temperance or fortitude.

In my opinion, we American Catholics have caught our fear of exercising prudence from some of our Protestant brothers and sisters. There’s a certain stripe of Protestant who thinks you can learn anything you want to know about God or morality by quote-mining the Bible. You find a passage that gives a command, you obey that command no matter how incongruous it is with your situation and even with the rest of the Bible, and that’s morality. You refuse to do anything you can’t find an exact chapter and verse for. I have been in conversation with this stripe of Protestant before, and everything I say they question with “Is there a verse for that?”

I once saw a Protestant comedian lampoon that kind of thinking. “I feel like a cheese sandwich this morning.” “Can you tell me where it says ‘cheese sandwich’ in the Word of God?”

Catholics would like to find “Cheese Sandwich” in the Word of God as well.