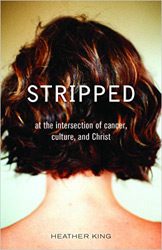

“I didn’t see my cancer a blessing—please!—but I did see it as a mystery. To consent to live in mystery, not to know all the answers, is another kind of poverty. The world sees any kind of poverty as cause for ridicule. Loser! But Christ’s kingdom is not of this world.” — Heather King, author, Stripped

This month at Patheos, we’re reading and responding to Heather King’s new memoir Stripped: At the Intersection of Cancer, Culture, and Christ. As the Editor of our Book Club, I skim a lot of “religion” books, but now and again, one grabs hold of me in a surprising way and calls me to stop and linger a while longer. Stripped is one such book. King’s interweaving of her cancer diagnosis with her lived faith as a Catholic convert (and recovering alcoholic) is exquisitely rendered, deeply moving and profound. Her writing about the Church, Christ and her own faith in the midst of a life-altering diagnosis begs you to slow down and ponder your own spirituality, while her honesty, intimacy and authenticity create a powerful expression of what it is to follow Christ through a very modern cancer diagnosis.

I was eager to ask Heather more about her writing, her faith, and how her journey with cancer changed her.

How did you choose the title for your book, Stripped? How does that express the heart of the book?

How did you choose the title for your book, Stripped? How does that express the heart of the book?

I like one-word past participle titles. I’d already written books called Parched and Redeemed. Next year I have two books coming out: Loaded and Famished.

Stripped in the context of the book connotes being stripped down: emotionally, spiritually. “He who loses his life for may sake will find it”…Many of us claim to follow Christ, but almost never will you find a person who has voluntarily taken on ANY kind of poverty: whether financial, emotional, social. Almost as rare is the person who’s become “poor” in some way in spite of themselves and who sees the poverty as a sign of favor, an opportunity.

Sickness of any kind is its own form of poverty. It so happened I’d also had the poverty of alcoholism—I’ve been sober 28 years now but I’ll still die an alcoholic. I’m an introvert in an extrovert culture. I’m a Catholic writer in a mainstream literary culture that tends to view belief in God as imbecilic. I’m single—which as a Catholic is to say celibate—and childless. I got a divorce and had my marriage annulled in the wake of my cancer diagnosis.

I didn’t see my cancer a blessing—please!—but I did see it as a mystery. To consent to live in mystery, not to know all the answers, is another kind of poverty. The world sees any kind of poverty as cause for ridicule. Loser!

But Christ’s kingdom is not of this world. Even in the worst of my drinking days, I was always engaged, curious. No virtue of mine but my heart never hardened. I was corrupt and I did corrupt things but my heart didn’t harden. Because of that, the longer I stayed sober, up to and through my cancer, I began to see my various kinds of poverty—and we are all poor—as my crown in a way, as the way to Christ.

As a Protestant reading your memoir, I was captivated by your writing about the Catholic faith — be it the evocative descriptions of the Eucharist and the Mass, or the intimate details of your prayer life, to your frank conversations with a recovering alcoholic priest. You write about your faith in a way I don’t see many others doing. How did you fall so in love with Catholicism and what do you find most compelling about it?

I didn’t fall in love with Catholicism: I fell in love with Christ. That’s a dangerous proposition.

My memoir Redeemed tells the story of my conversion. In brief, I was newly sober, newly married, working as a lawyer in Beverly Hills. And with no theological grounding whatever, I saw, re the lawyerdom, that the emperor has no clothes. The whole system of power, property, prestige on which politics, legal systems, armies, governments are run is built on sand. Those systems are by their nature false, and therefore eventually bound to fail, because whatever else they may claim to be about, they’re really about amassing power and money. They’re giant PR scams. We all blindly, obediently go along with them.

No-one knew that better than Christ. The truth abides in an entirely different realm and is most accessible to humble, simple people. That doesn’t necessarily exclude the rich or well-educated. But recently, for example, I heard a homeless person, a guy from the street with his entire worldly belongings in a paper bag, speak the kind of truth that interests me. He said, “I’m so so grateful. I’ve been sober 30 days. This is beautiful. Thank you. This is better than I deserve.”

This is better than I deserve. From a homeless person! When’s the last time we heard a politician or a judge or a five-star general or someone shrilly lobbying for yet another “right” say: This is better than I deserve? That homeless guy had the keys to the kingdom that Christ gives to the child-like, to the pure at heart. That’s not something you can learn in a theology class, however useful a theology class, or a law school degree for that matter, might be. You are certainly not going to learn it from any kind of mainstream American celebrity-obsessed, money-craving, violence-saturated culture. And that was what I was after. The truth at the heart of the world.

I found it in the Gospels. The notion of redemptive suffering. The crucifixion and resurrection I’d experienced in my own life. I’d already had to die to my identity as an alcoholic. I’d already in a sense been born again—born into gratitude, into wonder, into an intense desire for meaning and connection and to give all of myself.

I was in a profession that is based on lying. In the adversarial system of law, an attorney is compelled to “shade the truth.” You’re compelled to hide your own client’s information, to omit, to manipulate facts. I was in civil litigation but that’s true of both civil and criminal. In criminal you have the added egregiously skewed imposition of draconian punishment and incarceration on the poor.

And along comes Christ who says: “Say yes when you mean yes and no when you mean no. Anything else is from the evil one.”

Well, this is bracing stuff, working as a Beverly Hills lawyer, or anytime, anywhere. Christ’s teachings are hard, but they’re not impossible. Narrow is the gate and few will find it. But the gate is open! To everyone!

I wasn’t interested in secularism with good intentions, which is what tends to pass for religion in our culture. I’d always had good intentions: to love, to be loved. With good intentions, while drinking I’d slept with married men, had three abortions, squandered every gift I’d ever been given. That I was, and remain, a terrible sinner by the way was a great gift. My sins taught me the limitations of intelligence backed by will power, which is the god of our culture. I had tons of intelligence: I’d graduated from law school with honors in the throes of acute alcoholism. I had tons of will power: I’d passed the bar exams in three different states on the first try. Good intentions weren’t going to give me enough courage to quit my job as a lawyer and follow the call of my heart to write. Intelligence alone, backed by will power alone, wasn’t going to take me to the meaning, the Person, at the heart of the world.

I needed supernatural help. I needed the Body and Blood of Christ. I didn’t shop around for a religion: “Eeny, meeny, miney, mo, I like the candles and incense, let’s choose THIS ONE!” I never ever thought Let me choose the religion that will make me look good or feel good.

I didn’t choose at all. It chose me. I thirsted, I quested, I pondered, I read, I went around to a bunch of different churches. I read the Gospels. I saw the Gospels were living water, and Christ called me. There is nothing “like’” Catholicism. There was no question whatsoever of a “preference,” or a weighing, or this religion has this that I like and that one has that that I like. Either God took on human flesh, came to earth and pitched his tent among us, was crucified, died, buried and rose again and left us his Real Body and Real Blood or he didn’t. Either Jesus is who he said he was or there is no reason to live. There’s no middle ground. The stakes are life and death. That appealed to me immensely. The medieval romance: a perilous journey, necessarily undertaken alone, the risk, the quest for the Holy Grail. The fact that we don’t know how it will turn out. You have to be open to the surprise ending. You have to live your whole life in crazy, wild-card faith, in a world that has no conception whatsoever that the quest even exists, much less that you’ve given your life to it.

Your faith was integral to your journey through the cancer diagnosis and treatment. Can you say a bit more about that, for those who have yet to read the book? How did your faith accompany you in this journey?

My faith is integral to everything. Christ is the ground of my being. So he walked with me, accompanied me, as he does everywhere.

Just briefly. I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2000 and I ended up going against medical advice and declining chemo, radiation, and a heavy-duty estrogen drug called Tamoxifen. I did a ton of research and a lot of praying, and I consulted friends and spiritual advisors I trust. And in the end, my inner sense was that those harsh treatments would do more harm than good for my Stage 1, Grade 1 cancer. So I had the tumor surgically removed, out-patient, and that was it. I just kept living my life the way I’d been living it for years. And now fifteen more years have passed. I just turned 63. I don’t eat crap but I’m not obsessed with eating only organic. I adore gluten. I don’t take pills of any kind, not even vitamins.

But Stripped is in no way an anti-medicine screed. It’s an invitation to ask ourselves what Master we serve. That doesn’t mean the choice is between Jesus and the doctors. No, no, no. The question is whether we’re going to serve the master of fear or the Master of love. Do we have the courage to follow our own hearts over an authority figure: a doctor, a coach, a politician, a parent, a spouse, a friend, a religious or spiritual figure who may or may not be speaking with real authority? A culture that is increasingly based on the commodification of the human body, the human person?

In the temple, Christ spoke “with authority.” The only real authority is based on truth, beauty, love. I do feel if you hunger deeply enough, if you dare to ask the very deepest questions of the human heart, you will be led inexorably to Christ. There’s no-where else to go. But you have to be willing to be sort of drastically out of step, to bear the tension of profound emotional and spiritual poverty without making a show of it.

There are moments in the book where you provide very detailed information about what a doctor said to you about your cancer, or the unsympathetic way you were often treated by medical professionals. Was there a desire to share “the facts” about breast cancer, as well as the lived experience of moving through a diagnosis and treatment with your readers? What was behind that?

No, not really. I just wanted to be specific. The terminology of medicine, of cancer, is sort of naturally scary and creepy. We feel out of our league. We feel, Better leave this to the experts. Which in one way is a very sound thought. In another way, however, doctors are not gods. They still don’t know what causes cancer or what, if anything, cures it.

And as I say in the book if my days are going to be shorter than I’d hoped, I want to spend as few of them as possible in a doctor’s office. I would way rather be outside listening to the birds and watching the shadows on the sidewalk. Many of us are terrified of death because we’ve never fully lived. The more fully and richly we live, the less inclined we are to cling to it at any cost.

How did your faith life changed after your diagnosis?

The way I order my day didn’t change. I have a very simple, very solitary life. I pray every morning, write, answer correspondence, neaten and clean, take a walk, play the piano, ponder, listen to the birds, read.

I’m free to order my day pretty much as I like and in its way it’s extremely stringent. There is very little “fat” in my day, in my life. I appear to the outside observer be doing next to nothing but really my inner life is like boot camp. Ongoing examen, ongoing praise, forever contemplating, making connections, “working” in the best sense of the word. Alert, aware.

One main thing that changed was I realized was that my true “marriage,” my vocation, is writing and that I couldn’t both write and participate in the Sacrament of an actual marriage.

What did your cancer journey ultimately teach you about life, and death?

It was an experience, an incarnational experience of Garden-in Gethsemane suffering. The paradox is that my life is ever more full of that sword-will-pierce-your-heart joy that only comes with being in love with something or someone that can’t quite reciprocate in the way we long for. Christ chooses not to be available to us in the flesh—but then again, he IS available in the Flesh, in the Eucharist.

Then of course there are our fellow human beings—they never love us in quite the way we hope either!

And if we’re very lucky, and suffer a lot because of this unrequited love for the world and its people, and if we refuse to let our longing turn into cynicism or resentment or self-pity or jealousy or despair, we begin to see—Oh! This is Christ’s stupendous gift to us. This blood that flows from our ever-hemorrhaging hearts is meant to heal us and to heal the world.

What do you most hope to offer to your readers with Stripped?

An invitation to ask ever deeper questions about how we want to live, and how we want to die. An invitation to turn off our television sets, sit with the almost unendurable pain of our existential loneliness, and realize THAT IS WHY CHRIST CAME. We have a profound obligation to train ourselves to be able to discriminate between the true and the false. We’re called to hold ourselves to the highest possible standard of coherent, consistent reasoning, ethics, and behavior.

To follow Christ is an extreme sport: 24/7 we’re training. We’re athletes in a sense, as St. Paul said. Our aim isn’t to look good, to win in the worldly sense of power, property and prestige. It’s to become fools for Christ.

Read excerpts from Heather King’s book, Stripped, at the Patheos Book Club here.