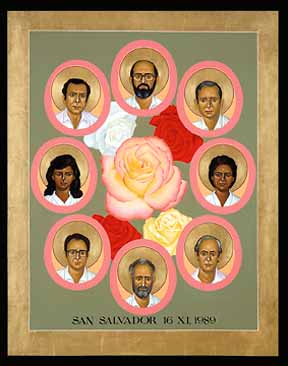

Sunday November 16 marks the 25th anniversary of the murder of six Jesuits, their housekeeper, and her daughter at the Universidad Centroamericana “José Simeón Cañas” (abbreviated as UCA) in El Salvador. The Jesuit university is remembering the murder with a series of programs that examine the work of the Jesuits and their contribution to the social development of Salvadoran society.

The anniversary is being remembered by many of the 28 Jesuit colleges and universities in the United States.

In his 2001 book A Stay Against Confusion (excerpt here), Ron Hansen described the purpose of the UCA by paying attention to the work of the leader of the Jesuits, Ignacio Ellacuría.

While the institution’s orientation was formally that of providing technicians for the economic and social development of El Salvador, he thought it was essentially affirming European values and structures, and fostering prosperity for the prosperous. Ellacuría felt the institution ought to fully engage the harsh realities of the Third World and, through teaching, research, and persuasion, be a voice for those who have no voice, to alter or annihilate the world’s inhuman and unjust structures, and help assuage the agony of the poor. With his forceful guidance and his editing of the monthly magazine Estudios Centroamericanos, the University of Central America would undergo an epistemological shift, orienting its ethos in the fundamental option for the poor and in the liberation theology formulated by Gustavo Gutiérrez, a theology founded on life in the risen Christ while it was focused on the institutions of injustice and death to which Latin America’s poor were subjected. [my links added to the original text]

Liberation theology was the subject of a 1984 instruction of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith that critiqued some strains “which use, in an insufficiently critical manner, concepts borrowed from various currents of Marxist thought.” There has been, to put it mildly, criticism of both liberation theology itself and those thinkers (often Jesuit) and institutions which support it. Yet at root, the work of the Jesuits at the UCA was about solidarity with the poor, a theme which has been consistent in Biblical teaching, the development of Christian spirituality, and recent Catholic social teaching from Rerum Novarum through Populorum Progressio to Evangelii Gaudium.

The legacy of the UCA martyrs will be that they marshalled the resources of a Catholic university for the sake of a proyecto social, a “social project” which aims to improve people’s lives. It is rooted not in the truncated anthropology of Marxist dialectical materialism but rather in something more radical: namely, the gospel. A document published just two years after the UCA martyrs, Pope John Paul II’s Centesimus Annus, gets at that anthropological foundation for which the Jesuits labored unto death.

Ron Hansen gets the last word:

The blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church, wrote Tertullian. All the faithful do not perish, nor suffer infamy or risk, but Christians are expected to be witnesses to those who did, and do. And then we will find that like the martyrs before them, the two women and six Jesuits murdered in El Salvador are, as José María Tojeira has written, dead “who continue to be profoundly active and alive … generating human spirit, generating human dignity, generating the capacity for dialogue and humane rationality, generating a critical capacity, a constructive capacity, and generating imagination.”