I am pleased to bring to your attention an extraordinary guest blogger, Michele Antaki.

Ms. Antaki is from a Syrian Catholic family and was raised in both Egypt and France. She has been a United Nations interpreter in New York for 27 years in four languages. Among other things, she worked briefly at CBS right after the 9/11 attacks where she monitored Al Jazzera. She holds an LLM from the University of Nice, France. A more complete biography can be found at the end of this post.

Ms. Antaki here analyzes the recent historic Christmas visit of the President of Egypt to a Coptic Christmas Mass, as well as its significance and impact.

A YouTube video of the event is linked below. An English translation can be found further down in this post.

The significance of President El-Sisi’s visit – and its historical context – cannot be understated.

We surely live in extraordinary times. Let us pray that we can all move forward in peace.

Please welcome Ms. Antaki.

_______

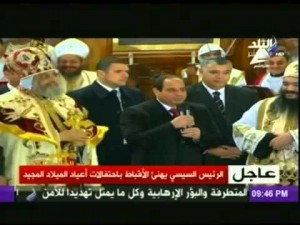

A truly momentous event took place last Tuesday in Cairo. As Christmas Eve Mass was celebrated at St. Mark’s Orthodox Cathedral by Coptic Pope Tawadros II, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt made a surprise and totally unprecedented appearance.

It was the first time ever in the history of Egypt that a Head of State had graced with his presence a Christmas Eve Mass – celebrated on 6 January due to calendar differences – and the highly symbolic significance of the gesture was lost neither on Egypt’s Copts, nor on its Muslim population.

Egypt’s Coptic community represents an important minority, one that is generally acknowledged and honored by the powers in place, despite some degree of marginalization and sporadic persecutions that took place throughout history, especially in recent times.

Copts are the ‘true’ Egyptians, whose lineage and claims to the land can be traced back to Egypt of the Pharaohs. The term ‘Copt’ is derived from the Greek word of ‘Egiptos’ or ‘Giptos’ (pronounced with a soft ‘g’, as in garment), which came to designate Egyptians during the Ptolemaic dynasty, of Queen Cleopatra fame, established after Alexander’s conquest.

With Egypt in decline, Cleopatra knew she could not match the might that was Rome, and so schemed to strike an alliance with Julius Caesar.

She threw a lavish celebration to honor the visiting Roman general, and it was also a politically savvy display of Egypt’s remaining splendor meant to secure her a deal on her own terms. Seduction was an important component of her strategy, and it enabled her to draw Caesar to her plan of jointly rule over a vast expanse of territory that was to include both Egypt and Rome.

Caesar’s assassination was to put an abrupt end to that dream, and although Cleopatra made a last-ditch attempt to revive it with Rome’s new strong man Mark Anthony, she could not prevent Egypt from eventually falling under Roman rule as a mere Roman Province. Egypt of the Pharaohs was no more.

At about the same time, a star would rise in Bethlehem to announce the birth of a child whose destiny would become inextricably linked to that of Egypt. After the end of Jesus’s earthly ministry, during the reign of the Roman Emperor Claudius around 42 AD, Saint Mark set out to evangelize Egypt where he began the theology school of Alexandria. It would grow to be a center of Christian learning and culture over the next few centuries.

The legacy that Saint Mark left in Egypt was a considerable Christian community in Alexandria. By the beginning of the 3rd century AD, Christians constituted the majority of Egypt’s population, and the Church of Alexandria was recognized as one of Christendom’s four Apostolic Sees, second in honor only to the Church of Rome. Christianity was the religion of the vast majority of Egyptians from 400–800 A.D. and the majority after the Muslim conquest until the mid-10th century.

Egypt became home to a particular brand of Christianity – Monophysitism – which considered that Christ’s divine nature had to be preeminent in the person of Christ and be given higher status than His human one. Hence the term ‘mono-physitism’ or ‘of a single nature’ (from the Greek term of ‘phusis’ for nature). This departure from Christian orthodoxy may have reflected the centuries honored Egyptian cult of, and reverence for, Pharaohs or God Kings. It has endured to this day.

In 641 AD, Egypt was invaded by Muslims from the Arabian Peninsula. Under Muslim rule, Christians were second-class citizens, they paid the Jizya (a protection tax on non-Muslims), and had no access to political power – but they were exempt from military service.

Their position improved dramatically under the rule of Muhammad Ali in the early 19th century. He abolished the Jizya and allowed Egyptians Copts to enroll in the army.

Gamal Abdel Nasser, in power 1952–70, paid no attention to the Christians and nationalized property and industry. Most of the land he confiscated was owned by Copts who were economically prosperous, and given to Muslims.

In addition, Nasser’s pan-Arab policies undermined the Copts’ strong sense of pre-Arab identity. Permits to construct churches were delayed, and the regime confiscated land and Church properties from Copts.

Anwar Sadat, in power 1970–81, was more favorable to the Copts, but his more moderate policies elicited a strong reaction from the Muslim Brotherhood, and that caused the Copts to emigrate to the West.

Hosni Mubarak, in power 1981–2011, provided some protection, but after his fall the Muslim Brotherhood launched murderous assaults on the Copts.

El-Sisi’s cathedral visit has to be seen against that sometimes uneasy cohabitation of the Copts with the Muslim population on their ancestral land.

Without discounting the shared Egyptian identity forged over several centuries, there is no denying that coexistence was not always smooth sailing.

Since the revolution that ousted Mubarak in 2011, and even after Morsi was deposed in July 2013, a wave of violence spread across Egypt, followed by the torching of dozens of churches and assaults on Christian property.

El-Sisi’s presence has also to be appreciated in light of the Egyptian massive mobilization – of moderate Muslims as well as Christians – against the ruling Muslim Brotherhood on 30 June 2013.

El-Sisi spearheaded the popular uprising, then deferred to popular demand that he run for president and, in preparation for this, he resigned from the army. After winning a landslide victory, he was able to position himself as the uniter of the Egyptian people across religious divides.

Furthermore, El-Sisi’s cathedral appearance must be read in the context of his stated desire to promote an enlightened vision of Islam and do away with an ideological extremism that is “antagonizing the whole world.”

His pleas in favor of a renewed vision of Islam were made on a couple of occasions and, more recently, on 1 January 2015 before an important Al-Azhar gathering of Islamic clerics and ulema, as well as officials from the Minister of Awqaf (Religious Endowments).

He was careful to frame his position as the rejection of an outdated ‘thinking’ and not of the religion itself. Still, in so doing, Sisi took the lead on one of the most divisive and sensitive issues facing the world today – that of Islamist militancy and supremacism.

El-Sisi cut short his visit to Kuwait and went straight from the airport to Saint Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral to make it on time, in a display of good-will towards Egypt’s largest non-muslim community. He arrived just as the service had begun and apologized several times for interrupting Mass. He was greeted by a jubilant congregation and his brief address received a standing ovation and was broadcast live on Egyptian State TV.*

As an amplification of his Al-Azhar’s declaration sternly denouncing the bloody religious extremism that is terrorizing nations across the globe, Sisi told the assembled congregation: “Egypt has brought humanism and civilization to the world for millennia and we are all here today to confirm that we are capable of doing so again . . . Allah willing, we shall build our nation together, accommodate each other, make room for each other, and we shall like each other . . . love each other . . . in earnest, so that people may see . . .”.

He asserted that Egyptians were one people and had to think of themselves not as Christians or Muslims, but “as Egyptians, just Egyptians.”

His address was often interrupted by frantic applause, clapping, and cheers of “We love you!” and “hand in hand.”

In contrast to an overwhelmingly positive reception from service attendees, reactions in Egypt were mixed on the day after, though the positive outweighed the negative. Copts were appreciative of Sisi’s good-will gesture that honored them, apart from a few complaints about the ‘inappropriate’ interruption of Mass.

Moderate Muslims also welcomed that solidarity-building move and hailed Sisi as the bulwark against Islamic extremism, in Egypt and in the entire region. There was, however, criticism from a minority of people objecting to what they viewed as his dictatorial rule and heavy-handed repression of dissent.

There were also the expected attacks from Muslim Brothers’ sympathizers. A comment on OnTV’s Facebook and YouTube pages quoted Sheikh El-Chaaraoui’s interpretation of a Koranic verse that Muslims should not try to please Nazarenes and Jews, only tolerate them. Another comment read: “Well done! You, Nazarenes, have lost the right to complain about your lesser status. Egypt is no longer a Muslim Nation – it has turned Christian, or so it seems!”

Christians Copts were traditionally said to represent about 10% of Egypt’s population in official statistics, but around the time of Morsi’s overthrow, a TV commentator revealed that the Copts’ real strength had been deliberately downplayed in the past by order of President Mubarak, presumably to curtail their political influence.

Recent revelations by Pope Tawadros in the written press suddenly put their number at 16 million (20%) inside Egypt, and 24 million overall. The Pope asserted that he stood by these figures, backed by a recently conducted census. The fact that Pope Tawadros was allowed to publicize this rectification, coupled with El- Sisi’s last overture towards the Copts, and his Al-Azhar’s extraordinary address, are all signs of his desire to build bridges with Egypt’s Christians, and the rest of the world.

The only question that begs to be asked remains, of course – will he be allowed to carry this through?

* The following is a transcript of El-Sisi’s remarks:

“I would like to say a few brief words . . . please, allow me . . . It was necessary for me to come and present my wishes to you. I hope that I am not interrupting your prayers. I wanted to tell you something . . . Throughout millennia, Egypt brought humanism and civilization to the whole world . . . And I’d like to tell you that the world is looking to Egypt even now, in this day and age and in the present circumstances, to . . . ”

Then, he interrupted himself to respond to cheers in the background:

“We love you too . . . Yes, we do!”

This elicited further shouts and cheers of “We love you!”

“I thank you very, very much but honestly, I don’t want his Holiness the Pope to be upset with me.

Listen, it is very important that the world should see us . . . that the world should see us, Egyptians . . . and you’ll note that I never use a word other than ‘Egyptians’ . . . It’s not right to call each other by any other name . . . We are Egyptians. Let no one ask ‘what kind of Egyptian are you? (from what religious denomination).

Please . . . please . . . listen to me . . . with these words we are showing the world the meaning of . . . we are opening a space for genuine hope and light. As I said, Egypt has brought a humanistic and civilizing message to the world for millennia and we’re here today to confirm that we are capable of doing so again. Yes, a humanistic and civilizing message should once more emanate from Egypt. This is why we mustn’t call ourselves anything other than ‘Egyptians’. This is what we must be – Egyptians, just Egyptians, Egyptians indeed!”

And echoing cries and cheers in the background, he confirmed:

‘That’s right, hand in hand!’ “I just want to tell you that Allah willing, Allah willing, we shall build our nation together, accommodate each other, make room for each other, and we shall like each other . . . love each other, love each other in earnest, so that people may see . . . So let me tell you once again ‘Happy New Year, Happy New Year to you all, Happy New Year to all Egyptians, Happy New Year to His Holiness the Pope’. Thank you but please . . . I won’t take more of your time . . . Happy New Year!”

________

Ms. Antaki is from a Syrian Catholic family, and was raised in Egypt and France. She holds an LLM from the University of Nice, France, and a PG Diploma of Conference Interpretation from the Polytechnic of Central London in Arabic, English, and French.

A UN interpreter in New York for 27 years in four languages, she has covered two Gulf wars, top-level political and Security Council meetings. She took part in field missions to Algeria during the civil war, and to the Occupied Territories. She covered the State visit of Yemen’s President Abdallah Saleh to Washington and did a three month stint at CBS after 9/11, monitored Al Jazzera, and wrote transcripts.

She holds translation certificates in five language pairs. Her recent translation work includes Palestine’s plea before the ICJ on the Partition Wall in 2003, and a six month stint at the UN Translation Service.