Like messiahs, monsters bridge divides, including those between disciplines. As David Skal claims, “Since it is in the nature of monsters to bridge divides, it should be no wonder that they offer an (un)natural tool for cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural studies, which almost, by definition, require some crucial encounter with some kind of Other.”[1] People often live with clear boundaries, like vampires that are neither living nor dead, but undead. Messiah figures supernaturally rather than unnaturally bridge divides, like Jesus as the God-Man.

I wonder if monsters also bridge divides as substitutes for messiah figures when we abandon them? Some Enlightenment thinkers found blood atonement repulsive. Consider Voltaire’s disgust, as he wrote derisively about Israel, the story of Jepthah, and human blood sacrifices: “With this, human blood sacrifices are clearly inaugurated; no point of history is better verified. One can judge a nation only by its archives, and by what it reports about itself.”[2] Since the Enlightenment, when Voltaire wrote these words, many cultured Westerners have similarly despised and jettisoned concern for blood atonement. Or have they?

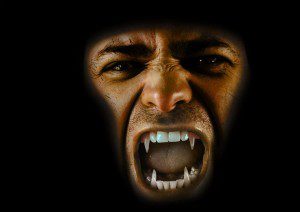

Consider our fascination with vampire figures like Dracula. Rather than shedding his own blood to give others’ life, Dracula sucks the life out of others so that he can survive as a vampire. Blood atonement has not disappeared, simply arisen elsewhere, and in reverse fashion. While some might view messiahs as monsters, I believe Jesus’ displacement creates monsters. Pop culture often provides intersections or bridges for reflecting upon different trajectories, including theology and horror as well as fantasy. Monsters can also serve as extensions of ourselves. According to NPR, Christian Grey in Fifty Shades of Grey was originally a vampire.[3]). How close of a resemblance is there between us and vampires? Do we suck the life out of people, or pour out our lives and lifeblood for others? Maybe disgust over blood atonement is nothing more than a symptom of a deeper delight—vampires. Just perhaps we love vampire monsters because they reflect our drives and passions more than messiahs like Jesus.[4]

[1]David Skal, foreword to Speaking of Monsters: A Teratological Anthology, edited by Caroline Joan S. Picart and John Edgar Browning (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), page xiii.

[2]Voltaire, Philosophical Dictionary, vol. 1, translated, with an introduction and glossary by Peter Gray (New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1962), page 326.

[3]See Neda Ulaby, “Christian Grey Began His Fictional Career As A Vampire,” National Public Radio, February 8, 2015.

[4] I am grateful for my interaction on this subject over the years with my colleague John W. Morehead, including this post. For more on his work, see Theofantastique: http://www.theofantastique.com/2008/04/20/gilmore-anthropology-and-monsters-in-cultural-imagination/