This post is a contribution to the Patheos Book Club discussion of Curt Thompson’s The Soul of Shame.

A lot of people are talking about shame these days. As liberated, progressive, and open-minded as we in the modern west imagine ourselves to be (and prove ourselves to be in many ways), contemporary culture seems like fertile soil for shame–and for shaming.

Children and college students all over the country are heading back to school. Now there’s an experience that is particularly ripe with the possibilities of shame.

Maybe you, my dear reader, find yourself troubled by the destructive effects of shame. Maybe you found this post by searching “What do you do if you find yourself in the middle of a shame storm?”

If that’s you, I certainly recommend to you Curt Thompson’s book, The Soul of Shame. Thompson is a psychiatrist who has worked extensively with patients whose personal and relational challenges stem in large part from the root problem of shame. He offers that clinical experience, as well as his scientific knowledge of the complex workings of the brain and mind (neurobiology), in an accessible, digestible way.

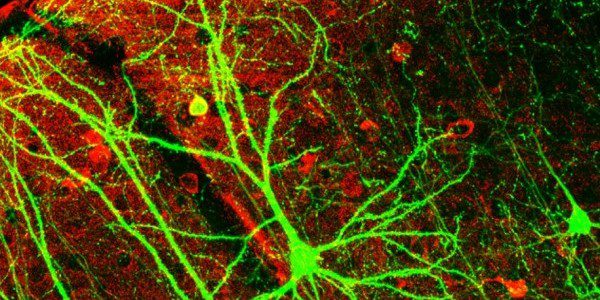

He begins his argument by addressing some contemporary findings of brain science, which show the “mind” to be a complex, embodied (not “abstract”), and relationally interconnected human phenomenon. To understand how to respond to the challenge of shame, we have to understand how the brain works and how the emotion of shame disrupts the mind.

For the mind to function in a healthy way, all nine domains that the mind encompasses need to be functioning properly (both internally and externally in relationship to experience and to other people–and to their minds). As Thompson puts it,

…the way our neurological system wires its responses to various emotional experiences is significantly influenced by the relational contexts in which those emotions arise. This means that the “nature versus nurture boundary is illusory when it comes to the development of the mind. (40)

When shame enters the picture, it disrupts the mind’s task, which is to “regulate the flow of energy and information.” It does this by disconnecting the domains of the mind from each other, which also causes a feeling of being “disconnected from other people” (40).

By the way, the recent Pixar film, Inside Out, portrays this disruption in a creative and vivid way with the falling

islands.

Shame targets the “integrated mind” and disintegrates it by causing a person to neglect other dimensions of the mind, focusing on only one domain or one interpretation of experience, and turning away from other people. Kierkegaard calls this disruptive experience “enclosing reserve”; when someone can’t handle emotional disruption, they turn away from others and from a full apprehension of reality and become less than a complete self.

But this withdrawal or “turning away,” which is an natural fight or flight instinct, does not solve the problem. In fact, it only intensifies it by adding more shame upon shame. The Shame Storm doesn’t dissipate; it rages harder.

So what do you do if you find yourself in the middle of a shame storm?

What you don’t do is to withdraw, enclose yourself, and work yourself over all the more with shame. You also can’t “self-talk” your way out of shame, because shame is deeper than language. Shame, as emotion, is pre-cognitive and primal. So you can’t just tell yourself you’re not the failure you think you are, or try to convince yourself that you’re not as bad as “they” say you are.

The mind has to change. The circuitry has to be re-routed. This is in fact possible, due to the plasticity of the brain and its openness to new experience and revised interpretations of reality. But again, this involves more than self-talk.

It requires that we pay attention. We must pay attention to what is really going on. What’s happening in my brain when I feel shame? What stories am I listening to? What am I paying attention to? As Thompson puts it,

As it is, most of what brings people into my office is a function of the degree to which they do not pay attention to what their mind is doing. Shame would have it no other way, and it routinely takes advantage of this tendency. When we do not attend in helpful ways to the various features our mind offers us, unfortunate things happen…

Once shame begins its march from a small slight, growing to geometric expansion, my attentional mechanism goes offline and remains so. Reversing this shaming event is as much about getting my attention back on track as anything else. (49)

Getting out of the shame storm will not happen in an instant. It requires a process of transforming one’s attention, of facing into the issues squarely, of being vulnerable with yourself and honest with others. It’s a deeply integrative and embodied process which no single prayer or thought can replace. In the apostle Paul’s language, the “renewal of the mind” (Romans 12:1-2) means “real change in real bodies.” (47).

The rest of Thompson’s book is devoted to spelling out in more detail how this change of attention, this renewal, can take place. So I will save that for another post.

Image Source (slightly cropped)