During a sesshin dokusan in 1981, after practicing with Katagiri Roshi for three or four years, I asked him if he’d ordain me.

During a sesshin dokusan in 1981, after practicing with Katagiri Roshi for three or four years, I asked him if he’d ordain me.

During this period, I’d been living a few blocks from the Minnesota Zen Center and like my fellow committed students, I attended most morning zazen sessions, 5am – 7am (including a short service) and evening zazen, 7:30pm – 9pm.

Roshi gave a talk every Wednesday night on a sutra or a koan, usually as part of a long series, so I didn’t miss many of them. We also had an extended day on Saturdays, beginning as usual at 5am but then including a general talk to the larger community, work, lunch and more work, usually ending about 4pm.

Once a month we had sesshin, usually just the weekend but four times a year we sat for seven days. Twice a year we had 100-day training periods that included a student talk that bumped back the start time to 4:30am, Monday – Saturdays and added a training talk by Roshi on Monday evenings. Sesshin talks and Monday evening practice period talks were almost always about Dogen’s Shobogenzo.

We lived a quasi-monastic life, probably sitting as much or more than many monastics, an extreme sport version of Zen training.

We also got a country monastery going during this period and had practice periods there, starting in 1983, that ranged from six to eight weeks, usually twice a year.

Except for those practice periods and a few trips here and there to train, I worked most of this time as a teacher in a juvenile detention center, forty hours a week. I did this for thirteen years until Roshi’s death in 1990. Some of my peers had trained like this with Roshi for eighteen years.

The spirit of this training is expressed by Katagiri Roshi in this way:

“The experience of enlightenment is important for us, but it is not enough. Again and again that enlightenment must become more profound, until it penetrates our skin, muscle, and bone.”

I mention this not so much to pat myself on the back – my arm got sore a while ago and I mostly quit that – but as an alternate training model to what’s being kicked around in Soto circles these days, let alone in some mindfulness circles where walking in the park, breathing and smiling, is regarded as the be-all and end-all of the buddhadharma.

At best, it looks to me like most Zen training models are directed at producing ministers to lead communities (tertiary in my training). At worst, much of what is offered as mindfulness is an utter trivialization of the subtle truth of the buddhadharma.

The “Why?” for Katagiri Roshi was something like this: “The subtle truth of the buddhadharma is so important for future generations that we’re practicing with our hair on fire to pass it on.”

That’s the mission that I signed on for when Roshi chose me as one of his successors.

Roshi trained us to sit through it all by sitting through it all with us. Sitting with someone who was deeply settled in zazen is really different from sitting on one’s own.

Roshi offered dharma inquiry with Shobogenzo, koan, and sutra as the inspiration and it continues to strike me as really quite extraordinary. Studying the dharma with someone with an eye for dharma is quite a different activity from reading Buddhist books on one’s own.

We used the traditional Soto forms of practice and yet Roshi stressed that the point was not to adopt esoteric mystical stuff, but through our dharma practice to embody birth-and-death deep reflection so that we could offer a path of deep reflection for others, making a contribution to humans in the rough times ahead.

Now, I’m not saying that he succeeded, because that remains to be seen. And I’m not saying he was perfect, because he wasn’t. We’ve all got our issues and he sure had his share – as do I. Years of intensive training left him a flawed human being. Sometimes radiantly so. Sometimes painfully so.

What I am saying is that my study with Katagiri Roshi was an apprenticeship, learned mostly through the body. Body time – sitting, working, living, practicing and studying together – was the single most important factor. Intimacy is the life-blood of this process, whether the teacher is into shikantaza or koan, both or neither. It is an intimacy that begins with the teacher-student relationship and opens to receive the 10,000 things.

I believe that apprenticeship Zen is the best way to learn Zen so it is the apprenticeship model that I offer. This training relies much more on intuitive processes than on a professional check-off system.

A word of caution: there are vulnerabilities for all parties in this way of training. To name just a few, it is difficult for a student to find a teacher with whom they sense affinity. It is difficult for a teacher also to find students who are compatible and capable. A student can put themselves down (or up). A teacher can put themselves up (or down). The whole thing can sometimes get carried way off track into a personality cult. An enormous investment of oneself is necessary and it isn’t a safe thing to do.

But then life isn’t safe either as it usually ends in a surprisingly untimely death.

Apprenticeships are also not convenient in our contemporary world, given the amount of body time that seems necessary for authentic training. The physical plant that is optimal for this kind of training is hard to come by and the compromises made to support the apprenticeship model may sabotage the heart of it.

Moreover, I’ve learned since then from others who’ve had this kind of training that apprenticeships in general often don’t feel good. Certainly, apprenticing with Roshi often didn’t feel good. A lot of the time, apprenticing with Roshi was boring. He rarely said a kind word to me and I often felt like there was something important that I wasn’t getting or that I should be doing. Sometimes he was bitingly critical of me. Some of that was very helpful.

This is a challenge particularly in our culture that stresses feeling good as the most important thing. I’m with Leonard Cohen on this one: “I don’t trust my inner feelings, inner feelings come and go.”

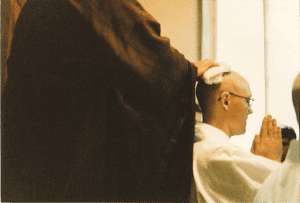

When I asked Roshi to ordain me, the words I chose were, “I want to be your disciple.”

I didn’t really know what I was saying. I meant that I wanted to be a Zen priest, because that seemed like the best way to study with him, but he probably heard that I wanted to be his successor. In any case, I didn’t know what being a Zen priest would mean. Nothing was spelled out in advance and there were no guarantees. Look, put your body in it and learn was the training method.

Roshi sat silently – and this guy could really really shut up – for what seemed like at least several minutes. Then he gruffly blurted, “It’s not so easy, anyway.”

He said a lot there. I’ve found that “not so easy” is unavoidably important.