Note: This is the first part of five – talks from last year’s Rohatsu that students (Brian, Ryan, Erik, and Vera-Ellen – thank you!) transcribed and I edited. The others will be posted here over the next couple weeks.

Note: This is the first part of five – talks from last year’s Rohatsu that students (Brian, Ryan, Erik, and Vera-Ellen – thank you!) transcribed and I edited. The others will be posted here over the next couple weeks.

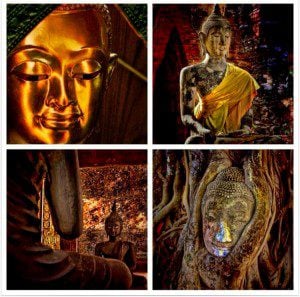

“Shakyamuni Buddha saw the morning star, and realized enlightenment. He said, ‘I together with all beings and the great earth attain the way.’ At age nineteen Shakyamuni leapt over the palace walls in the dead of the night and shaved off his hair. After that he practiced austerities for six years. Subsequently he sat on the indestructible seat, so immobile that spiders spun webs in his eyebrows and magpies built nests on top of his head. Reeds grew up between his legs as he sat tranquilly and erect for six years. At the age of thirty, on the eighth day of the twelfth month, as the morning star appeared he was suddenly enlightened. ‘I together with all beings and the great earth attain the way’ is his first lion’s roar.'” – “Shakyamuni Buddha” from Keizan’s Record of Transmitting the Light,

This is an expression of the source, the essence, of Shakyamuni Buddha’s way, of the Zen way.

A real person, Shakyamuni, saw the morning star and then he acted – walking about, lying down, carrying his begging bowl, giving dharma talks.

We emulate the Buddha as we commemorate his enlightenment today and every day. We join with other practitioners sitting around the world this week. Doing what the Buddha did.

But what is it that the Buddha did? It’s very important to be crystal clear about this essential principle of the buddhadharma – the heart of the Great Matter.

In ancient times there was a certain form for the Buddha way. The Buddha was a renunciate, maintaining all the two-hundred and fifty precepts. Eating just one meal a day. Wandering around ancient India. And there are those today, our Theravadin brothers and sisters, who maintain that great way.

Also over the past two-and-a-half millennia, numerous streams of the buddha-dharma have sprung from this one source. What is the essential principle of the buddha-dharma, that we all maintain together?

One of our ancestors in the Soto family line of buddhadharma, Keizan Jokin, was a Japanese monk, born in 1264, twelve years after Dogen died. Keizan wrote the passage about Shakyamuni Buddha (quoted above) in what became his best known work. It continues to impact us today and in our Harada-Yasutani koan curriculum, it is the source of the last major koan collection taken up. In Record of Transmitting the Light, Keizan offers us enlightenment stories, commentaries, and verses on all of the buddha ancestors from Shakyamuni Buddha up to his teacher’s teacher, Koun Ejo.

Again, what is the essential principle?

A necessary condition to realizing this principle is demonstrated by Shakyamuni sitting on the “indestructible seat, so immobile that spiders spun webs in his eyebrows and magpies built a nest on top of his head. Reeds grew up between his legs as he sat tranquilly and erect for six years.”

This is our practice especially during sesshin, truly becoming zazen people together. Sitting through it all. As you know, in the fuller story of Shakyamuni Buddha as he sat down under the bodhi tree, all sorts of waves of delusions assailed him. Armies of Mara. Beautiful dancing women. All sorts of anger, greed, ignorance opportunities came at him wave after wave after wave. And he sat upright and relaxed, through it all.

One-pointedness like this requires not only strength but also softness in sitting. Keizan says that “reeds grew up between his legs.” Make your sitting like a reed. Reeds are very strong and also very flexible. These two qualities together, strength and softness, are the qualities of mind, heart, and body that we have the opportunity to open up to now.

If you just try to be strong and sit tough through it all, that sitting is like a twig that breaks easily when the strong winds of delusion blow. Find the way to be in zazen with body, heart, and mind, as if you are a reed.

Keizan was just such a person. His grandmother was one of Dogen’s benefactors and students. It is thought that she also was a benefactor of Myozen who was Dogen’s teacher that Dogen accompanied to China. Keizan’s mother became a nun at an early age, and it’s quite a mystery where Keizan came from – his mother was a celebate nun who appears to have given birth to little baby Keizan via immaculate conception.

After Keizan’s birth, his grandmother raised him. From his early years he was told that he was a very special child and had a great future. When he was just seven, his grandmother brought him to Eiheiji, and he became an attendant for Ejo, Dogen’s direct successor. After that, Keizan grew up at Eiheiji.

As Ejo became old, Keizan studied with several monks who had been around Dogen, including Jiun, who was a Chinese monk that had met Dogen in China and then came to Japan to train with Dogen and eventually succeeded to Ejo. Jiun was an early abbot of Eiheiji.

Keizan then went on pilgrimage and studied far and wide. He was especially interested in Shingon practice, the esoteric school of Buddhism. He also trained in several of the branches of the Rinzai Zen, branches that had come to Japan just shortly after Dogen founded the Soto line. Meanwhile, his mother remained a monastic and was committed to training women and devoted to Kannon. She was also much involved in Keizan’s life – a true helicopter parent, pushing Keizan this way and that. Guiding his training from afar.

Keizan eventually settled down with Tetsu Gikai, who had also received transmission from Ejo but had trained extensively with Dogen. One day Keizan went to Gikai for instruction and Gikai asked him about this principle of the buddhadharma – the essential principle.

“Show me ordinary mind!” demanded Gikai, inviting Keizan to show his true heart.

This is a fragment, a punch line, from the well-known koan, “Ordinary Mind is the Way.” Gikai wanted Keizan to do it, not talk about it – to do as the Buddha did. “Show ordinary mind, right now!”

Keizan started to open his mouth but Gikai hit him right in the kisser. That seemed to shut up the young prodigy.

But that wasn’t the end of it. Keizan shut up and had an explosion of bodhicitta, way seeking mind, yearning to open to openness.

“What is It? What is ordinary mind? What is the essential principle of the buddha-dharma?” we can imagine Keizan’s intense pursuit of the truth.

Keizan threw himself into zazen night and day. Sitting through it all. Sitting like the Buddha had done. Sitting like all the ancestors following the Buddha, including Dogen, Ejo, and Gikai. Sitting through it all in the manner that you too are invited to sit right now.

This is the necessary condition for realizing the essential point of the buddhadharma. It is necessary to become a zazen person, going against the grain of what is fashionable today in our “get-something-fast-and-easy” culture. Becoming a zazen person and sitting through it all isn’t fast and easy. It’s hard work in the trenches. The glamor wears off rapidly. Maybe it’s already worn off for you, or maybe that’ll happen some time later. Seven-day sesshin are great ways to wear through glamor.

We’re given the opportunity by the structure of sesshin to let go of the intention that we walked in the door with and find something deeper, something more essential. Dogen refers to this as working in the dark and subtle night. This is the practice of becoming a zazen person. Sitting until reeds grow up between your legs. Spiders spinning webs in your eyebrows. Magpies building nests on your head. What a process! What an incredible practice!

Keizan continued sitting, continued emulating the ancients in this way. Of course, part of emulating the ancients is also to walk, wear the robes, and fold our napkins just as our buddha ancestors have done. But when folding our napkin correctly, don’t lose sight of the heart of the matter. Sit the way the ancients sat. Allow yourself to be run through by the lineage of practitioners who sat like the Buddha sat.

In the Fukanzazengi, Dogen tells us, “We find that transcendence of both mundane and sacred, and dying while either sitting or standing, have all depended entirely on the power of zazen.”

As I said, our zazen must be strong and soft. Zazen becomes strong by sitting through it all – it’s not something that we’re necessarily born with. We exercise zazen and zazen becomes strong. When we let zazen just lay on the couch, zazen just gets flabby. Zazen must be strong. And then the transcendence of mundane and sacred can occur. Transcendence depends upon it.

Good and bad, right and wrong, success or failure, me and you, in or out, up or down. The transcendence of the whole works depends entirely on the power of zazen. Indeed, dying while either sitting or standing is to do each thing completely with no part left out. Doing as the Buddha did in each thing completely. Folding the napkin. Walking across the floor. Sweeping the deck. Carrying the firewood. Ringing the bell. Each thing doing as the Buddha did.

There was an important nun in twentieth century Japan, Nogami Senryu Roshi, who would always instruct her students, “Die sitting! Die standing!” When she became very old, in her nineties, one of her students came into the Buddha hall and saw Nogami Roshi walk into the Buddha hall and stand in front of the Buddha and shout, “Die sitting! Die standing!”

Then she collapsed, and died. Her disciple ran up to her, held her, and said, “You did it! You did it!” And in that they met completely. The student met Nagomi Roshi’s dying-standing by dying-holding. No whimpering in the mind.

Back to Keizan sitting through it all. Even though he was a golden child, he was just like us with lots of problems. His mother was always messing with him. All these old men that want him to do this and that. What’s a guy to do? What is the ordinary mind?

Then one night as he was sitting, he heard the wind blow around the corner of the temple and he had great realization of the essential principle of the buddha-dharma. He went to see Gikai and when Gikai saw him coming he said, “What is it that you’ve realized?”

Keizan said, “It’s like a black ball rolling through the dark night.”

Just one doing! Die sitting. Die standing.

Gikai didn’t accept his presentation, perhaps because it was too discursive. Gikai said, “That’s not clear, explain again.”

Keizan said, “When it’s time for tea I drink tea, when it’s time for gruel, I eat gruel.”

Gikai then accepted his realization.

This essential principle of the buddha-dharma for which we become zazen people. To realize this, sitting through it all is a necessary condition.

Don’t listen to the dharma sound bites and the advertisements, the birds and the crows and the magpies, calling and telling you there is an easy way. The easy ways available now are merely commodification of the buddhadharma and not the real deal.

The only way is leaping through. The only way through is to become a zazen person. Then realize the essential point of the buddhadharma, doing as the Buddha did.